Lynn Cohick, The Letter to the Ephesians, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2020), 520 pages.

So I decided to do something I’ve never done before in the last 50 years of studying the Greek New Testament. I read right through a major commentary skipping nothing. It turned out to be very worthwhile. In fact, it was rather like writing such a commentary, which I have done on Ephesians (see my The Letters to Philemon, Colossians, and Ephesians, 2007). Lynn Cohick’s commentary covers a lot of ground, and interacts with a large body of literature, and no commentary can be expected to deal with everything. But surprisingly missing apart very brief mentions in the Introduction and late in the commentary when one gets to the peroration at 6.10-20, is any interaction to speak of with the reading of Ephesians as a rhetorical discourse within an epistolary framework— which is, in fact, what Ephesians is. The latter was long ago recognized not only many of the Greek Church Fathers such at John Chrysostom, and Latin fathers like Augustine, and also the Reformers, but also by many of the recent treatments of Ephesians by very fine scholars such as Roy Jeal and Andrew Lincoln. This oversight, or neglect, whichever it is, is strange, because it would have strengthened this commentary considerably when it tries to make a good case for the Pauline authorship of this letter (which it does do).

Those who know the history of rhetoric know that all the way back to the time of Aristotle, and even before there were handbooks, guides to the art of persuasion. These ancient cultures were primarily oral cultures, not cultures of texts, not least because the literacy rate in the Greco-Roman world was at most about 20%. And in any case, all kinds of texts, including letters were read out loud to audiences, and they had oral and aural features by design. So far as the historical evidence goes, there were no letter writing handbooks before or during Paul’s time. In fact, letter writing was treated as a rhetorical exercise, as part of the progymnasmata, elementary education focusing on and featuring the art of rhetoric. When Theon in the first century A.D. began to teach letter writing to his students who were studying the progymnasmata he told them— ‘compose these fictional letters as a rhetorical exercise and in the form of what is called prosopopoiia’ (see Peter Lampe’s essay in Paul and Rhetoric ed. J.P. Sampley, 2010). Furthermore, classics scholars have shown that even brief letters by a Pliny, or a Seneca reflect the structure— proposition, an objection, an argument, and a peroratio, (see Pliny’s Ep. 1.11 and 2.6 and the 13th-15th Epistula morales of Seneca).

Had attention been paid to the rhetorical interpretation of Ephesians, it could have been pointed out that Paul has deliberately chosen the Asiatic style of Greek rhetoric, with its long sentences, and many repetitions of key terms in this letter because this letter is written to an audience, wait for it— in the province of Asia, where such a style of Greek speaking and writing originated and was popular. The change in style does not reflect a change in authorship, it reflects a change in audience from say 1 Corinthians, or Romans, or Philippians or 1 Thessalonians. Paul is versatile in his use of Greek, like many ancient orators and writers. (see now the 2nd edition of the textbook I’ve done with Jason Myers, NT Rhetoric, with a bibliography which lists hundred of rhetorical studies done in the last 25 years, as well as detailed Appendices on ancient education and the Progymnasmata).

Since George Kennedy revived the study of reading the NT in light of ancient rhetoric while he was teaching at my alma mater (UNC in the 1970s, the very man who taught me Greek in the first place), it has been increasingly recognized that one neglects the rhetorical reading of various parts of the NT at one’s peril. For instance, the considerable body of work by scholars like Kennedy or Hans Dieter Betz or Margaret Mitchell or J. Paul Sampley or many other have demonstrated this again and again. The bibliography in the 2nd edition of my volume New Testament Rhetoric, done with Jason Myers shows that there are now hundreds of articles and monographs written in the last 25 years that recognize and draw on rhetorical analysis of the NT, and especially Paul’s letters.

The reason Paul sends this document with an epistolary prescript and postscript, is because he is far from the audience, indeed he is confined to his current location probably in Rome, and so the discourse he would have delivered orally in the province of Asia had he been there, had to be written down and sent off as a letter, for Tychicus or someone else to read out loud to the audience, or more likely audiences (because Ephesians appears to be a general circular letter probably written at the same time as Colossians).

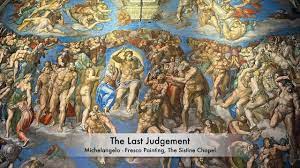

It would have further helped this commentary if it had been recognized that we are dealing with the rhetoric of the present, epideictic rhetoric, the rhetoric of praise and blame, a sermon of sorts which focuses on what unites the body of Christ, and Christ with his body, what unites Jew and Gentile, slave and free, male and female in Christ, indeed what unites the whole cosmos, both in heaven and on earth, namely the person and salvific work of God, Father, Son, and Spirit.

And what an eloquent sermon it is, not offering arguments but rather prayers, and praises, and encouragements and both theological and ethical food and support for the tiny Christian communities in Asia struggling to survive in a polytheistic and antagonistic culture where not just human opposition but the powers of darkness are at work. In such an environment, Christians need to put on the full armor of Christ just to stand and withstand the war that is being waged against the truth and against them by multiple sorts of opposition. But I have dwelt on this major lacuna in this commentary too long. Now, I want to turn around and tell you some of the good things about this commentary, which in numerous respects deserves high praise.

In the first place, this commentary provides us with a excellent, detailed grammatical and historical study of the Greek of Ephesians, and it is written in good clear English that any pastor, or teacher, or Bible study leader can understand and learn from. Lynn is very fair, and very thorough in her exegesis and treatment of the such matters. There are also first rate Excursi in the commentary that give more detailed treatment of key subjects, especially difficult ones like the treatment of slavery and slaves in the household codes. More on this in a moment. There is also a very good treatment of the theological and ethical substance of this discourse, although I could have wished for much more interaction with Markus Barth’s fine treatment of the issue of what Paul means by the phrase ‘in Christ’ and how it is Christ himself who was destined in advance before the foundation of the universe to be the fallen world’s savior. Believers are only elect or saved in Him, our representative, because we did not exist before the foundation of the universe to be predestined. Salvation is by grace and through faith in Christ, the destined one. Salvation does not transpire by individuals’ fates or destinies being pre-determined by God before they even exist. What is true is what Romans 8 says is true— for those who love God and are called according to purpose/choice, God has destined those who are Christians to ultimately be conformed to the image of Christ by means of sanctification now and resurrection when Christ returns. The future is as bright as the promises of God for those who are in Christ by grace and through faith.

Lynn brings to this commentary various detailed studies about the role of women in the ancient world, but also about the social history of parents, children, slaves, as well as clear knowledge about ancient economies and how all of this comes into play in the household codes and elsewhere in Ephesians. There are helpful discussions about unique phrases like ‘the heavenlies’, or what Paul means by ‘the middle wall of partition’. There is a very fine discussion near the end about soldier’s armor, and the analogies Paul is drawing on in Ephes. 6 in his peroration about how Christians can protect themselves by deliberately drawing on the truth, on their faith, on the their own previous experience of salvation in a hostile environment. The discussion in Ephesians 6 is about standing and withstanding the onslaught. It is not about going on the offensive through a deliverance ministry against ole Lucifer and his gang of thugs.

But the most helpful detailed discussion in the whole volume is on wives, children, slaves, and how Paul is changing the paradigm within the Christian household by calling for mutual submission between all Christians including husbands and wives, by treating children and slaves as moral agents and persons of worth in their own right who can respond to ethical imperatives. Paul is by no means baptizing the hierarchial status quo in the ancient extended family and calling it good. To the contrary he is changing the way Christians should look at those family relationships. But of course he has to start where his audience actually is, de facto, and then put the leaven of Gospel change into the already existing relationships of Christians in order to deconstruct the fallen domination structures that exist at every level of ancient society, even within families.

There are of course places where one could have wanted Lynn to say more about difficult concepts, for example about what in the world Paul means about ‘families in heaven’ or about believers already being seated in the heavenlies with Christ. And where exactly are the prince of the power of the air and dark forces in the heavenly realm located? Hopefully not in Paradise, or as Paul calls it in 2nd Corinthians—the third heaven. It is the measure of a good commentary that it teases the mind into active thought, and this commentary certainly does that in a helpful way from start to finish. This commentary definitely belongs on your shelf with other good Ephesians commentaries.

One more thing. Why in the world does this commentary have a cover image of Mary being confronted by an angel, from the Gospel annunciation story on it? This makes no sense at all.