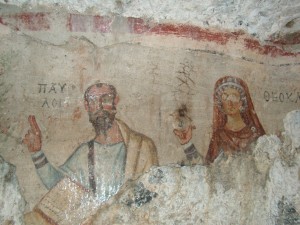

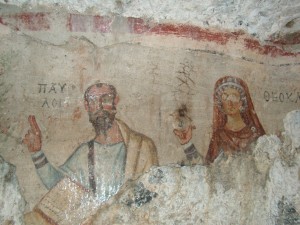

Paul and Thecla the earliest image of Paul in the cave of worship above Ephesus.

(Here is a nice piece by Todd Still my colleague and friend on women, Jesus and Paul. See what you think—- BW3)

Jesus and Paul on Women: Incomparable or Compatible?

Todd D. Still, Ph.D. • William M. Hinson Professor of Christian Scriptures

George W. Truett Theological Seminary • Baylor University • Waco, Texas

1. Introduction

Five years ago, a book that I edited appeared in print under the title Jesus and Paul Reconnected: Fresh Pathways into an Old Debate (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007). In that volume, six noted New Testament scholars (namely, John M. G. Barclay, Markus Bockmuehl, Beverly Roberts Gaventa, Bruce Longenecker, Francis Watson, and Stephen Westerholm) compared various aspects of Jesus’ thought and practice to that of Paul’s. One comparison not explored there that I would like to address here pertains to the views of Jesus and Paul with respect to the role of women in ministry and mission.1

If skeptical curiosity or even unbridled incredulity best describe your initial reaction to the announced topic of this essay, you would by no means be alone. George Bernard Shaw, for example, would have thought a comparison along such lines to be a royal waste of time, thinking that there is no need to compare the incomparable. As it

1 This essay had its beginnings as a plenary lecture for a Christians for Biblical Equality conference held in Houston, Texas in April 2012. I would like to thank CBE Houston for the invitation to speak at the event and for their enthusiastic reception of my address. This article is dedicated to that organization and its President, Dr. Mimi Haddad.

happens, on one occasion the Irish playwright depicted Paul as the eternal enemy of Woman’.2 Furthermore, Shaw asserted,

[Paul] is no more a Christian than Jesus was a Baptist; he is a disciple of Jesus only as Jesus was a disciple of John. He does nothing that Jesus would have done, and says nothing that Jesus would have said…. He was more Jewish than the Jews, more Roman than the Romans, proud both ways, full of starling confessions and self-revelations that would not surprise us if they were slipped into the pages of Nietzche.3

Shaw’s presumed misgivings notwithstanding, in what follows I will seek to compare the role of women in the work and witness of Jesus and Paul. In doing so, I will likely confirm one view that most readers of this journal already hold—women in general and women in ministry in particular have a friend in Jesus. I will also attempt to challenge herein what I regard to be a common, albeit mistaken, notion—that Paul is the ‘eternal enemy of Woman’. Indeed, I will contend women have a friend in Paul as well.4

2 See Shaw’s ‘The Monstrous Imposition upon Jesus’, in The Writings of St. Paul (ed. Wayne A. Meeks and John T. Fitzgerald; New York/London: Norton, 2007), 415-19 (on 417).

3 Shaw, ‘Monstrous Imposition’, 419.

4 Even if a given person already regards Paul as more friend than foe, more hero than heel, more saint than scallywag, there are any number of others—not a few of whom are thoughtful, faithful Christian women—who would prefer to ‘throw the apostle out with the bathwater’. Perhaps this piece will give the latter cause for pause.

In what follows my aim is straightforward, though not simple. My goal is to demonstrate that women played a pivotal role in both Jesus’ earthly ministry and in Paul’s Gentile mission. Having done so, by way of conclusion I will ask a question whose answer will, I hope, be obvious enough by then. The ‘sixty-four dollar question’, as it were, is this: ‘If it was the practice of Jesus and Paul to join hands with women in mission and ministry, should not this be our contemporary practice as well?’

2. Women in the Time and Ministry of Jesus

To the extent that our extant literary sources are at all indicative of lived-experience, first-century A.D. women were seldom afforded the dignity due them and typically lacked the opportunity to affect (much) socio-religious change. Taken together, it was usually thought that women were meant to be subservient daughters and wives and that they were ill-suited for public life.5 The negativity with which women were all too frequently regarded is disturbingly, even chillingly, captured in the second-century B.C. writing known as Ecclesiasticus or Sirach. Sirach 42.14 states, ‘Better is the wickedness of a man than a woman who does good; it is woman who brings shame and disgrace.’

That being said, early Christian authors were not necessarily more affirming of women. For example, Tertullian, the late second and early third century A.D. Christian theologian from Carthage in North Africa, could depict women as ‘the devil’s gateway’

5 See further, e.g., Sarah B. Pomeroy, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity (New York: Schocken, 1975), and Eva Cantarella, Pandora’s Daughters: The Role and Status of Women in Greek and Roman Antiquity (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987).

(De cul. fem. 1.1.2-3) and as ‘vipers’ (De bapt. 1.2).6 Such chauvinistic, if not misogynistic, statements cause even some of the most controverted and disparaging Pauline comments regarding women and wives to pale in comparison.7 We will have more to say about Paul and his perception of and instruction regarding women/wives below, but first let’s consider Jesus’ treatment and inclusion of women in his earthly ministry.

As we begin, allow me to anticipate our conclusions with respect to Jesus’ regard for women and their involvement in his life and ministry by quoting David M. Scholer.

[A]s a Jewish male in an androcentric, patriarchal society, Jesus’ respect for women as persons of dignity and worth and his inclusion of them as disciples and proclaimers in his life and ministry was very significant in its own first-century context for women and their place and activity in ministry in the earliest churches [indeed, I would add, Pauline churches] and is important as a heritage for both Jewish and Christian people today.8

6 On Tertullian’s (mis)appropriation of Paul, see Todd D. Still and David E. Wilhite, eds., Tertullian and Paul (London/New York: T&T Clark, 2012).

7 E.g., ‘Woman is the reflection of man’ (1 Cor. 11.7); ‘Women/wives are not to speak, but should be subordinate, as the law also says’ (1 Cor. 14.34); ‘Let a woman/wife learn in silence with full submission. I permit no woman/wife to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent…. She [i.e., woman] will be saved through childbearing…’ (1 Tim. 2.11-12, 15a).

8 David M. Scholer, ‘Women’, in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels (ed. Joel B. Green and Scot McKnight; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1992), 880-87 (on 881).

In his serviceable article, Scholer supports his claim that Jesus treated women with dignity and afforded them worth by noting that, for one thing, he healed women. Undaunted by contact with women, even those regarded as ceremonially unclean, Scholer notes that Jesus healed, frequently with touch involved, Peter’s mother-in-law (Matt. 8.14-15; Mark 1.29-31; Luke 4.38-39); Jairus’s daughter and an unnamed woman with the twelve-year flow of blood (Matt. 9.18-26; Mark 5.21-43; Luke 8.40-56; cf. Lev. 18); and a woman who had been crippled for eighteen years (Luke 13.11-17). No less touching is the way Jesus addressed these females. ‘Talitha cum (“Little girl, get up!”)’, he said to Jairus’s once-dead daughter. ‘Daughter’, he calls the ritually unclean woman who had suffered from hemorrhages for twelve years and from doctors who took her money and her hope but affected no cure. She was sneaky, and Jesus was busy, but she was a faith-filled daughter wanting and waiting to be made whole. Jesus was able and willing to bring her peace. Additionally, Jesus sought to teach a synagogue leader that a woman who had been crippled for eighteen years whom he had healed on the Sabbath was far more valuable than a beast of burden. She was not dispensable animal, but an invaluable ‘daughter of Abraham’ (Luke 13.15-16).

Jesus also came to the defense of women with whose sexual reputations were called into question (e.g., Luke 7.36-50). While not condoning promiscuity, he did not condemn women who were (thought to be) promiscuous nor turn a blind eye toward the adulterous thoughts and acts of men (note, e.g., Matt. 5.27-30; cf. Mark 9.42-48).

Far from being inconsequential or token, Jesus viewed women as full participants in his mission and in the kingdom of God. Fortunately, Luke, the Gospel ‘which shows

the greatest interest in women in the life and ministry of Jesus’,9 names a number of Jesus’ women followers/disciples, including, Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Susanna, ‘who provided for [Jesus and the Twelve] out of their resources’ (8.3). Luke also tells Theophilus and those privileged to read over his shoulder about Mary and Martha of Bethany (10.38-42), the former of whom is said to have chosen ‘the better part’ by sitting at the Lord’s feet and listening to what he was saying. Not a few women were also present at the cross, burial, and empty tomb of Jesus. Taken together, the canonical Gospels indicate that the female witnesses of Good Friday and/or Easter Sunday included: Mary Magdalene, Jesus’ mother named Mary, as few as one and as many as three other Mary’s, Salome, Joanna, and the mother of the sons of Zebedee. As it happens, these ‘gospel women’ were the first to learn about and to tell of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead.10 So pivotal and central a role is Mary Magdalene thought to have played in bearing witness to the Twelve regarding the Risen Jesus that she would latterly be depicted as the apostola apostolorum (‘apostle to the apostles’).

9 So Scholer, ‘Women’, 885.

10 See Richard Bauckham, Gospel Women: Studies of the Named Women in the Gospels (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002). Note also Ben Witherington III, Women in the Ministry of Jesus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984). Cf., too, the lesser known volume by Evelyn and Frank Stagg, Woman in the World of Jesus (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1978).

3. ‘Paul and the Eschatological Woman’11

Although Mary was among the first to see the risen Jesus, before too long there would be a number of other eyewitnesses. In addition to the eleven (see, e.g., Matt. 28.16), the seven (note John 21.2), and the two disciples traveling to Emmaus (so Luke 24.13-35), Paul reports in 1 Cor. 15.5-6 that after having appeared to Cephas and the Twelve, Jesus subsequently ‘appeared to more than five hundred adelphoi (lit., “brothers”) at one time, most of whom [were then] still alive, though some [had] died’. It strains against credulity to think that there were no adelphai (‘sisters’) among these five hundred adelphoi. (In fact, in that day adelphoi typically included adelphai.) Thereafter, Paul tells the Corinthians who were contending that the dead are not raised, that the Lord appeared to James (i.e., James the ‘Just’, the ‘brother’ of Jesus), then to all of the ‘apostles’, the precise identity of whom remains a mystery. Then, Christ appeared to the last and least of the apostles; he appeared to Paul (15:7-9).

Paul’s apocalyptic encounter with the risen Christ would prove to be a ‘game-changer’, not only for him but also (and I exaggerate not) for human history (Gal. 1.12, 16). The zealous Pharisee, who regarded Jesus accursed of God and who was ‘hell-bent’ on eradicating the Christian cancer growing on the body Jewish, would change his mind and his ways. Indeed, he began to preach ‘the faith he once tried to destroy’ (Gal. 1.23). If in the years immediately following his conversion/call, Paul spent time processing this encounter and preaching Christ in Arabia, Syria, Cilicia, and Cyprus, the time would

11 For the wording of this subheading, see E. Earle Ellis, Pauline Theology: Ministry and Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 53-86.

come when the apostle would take his ministry and message further afield—to Galatia, Asia, Macedonia, Achaia, and even Italy.

The Apostle Paul’s missional and ministerial modus operandi, at least in retrospect as we put various bits of evidence together, appears to have looked something like this. To begin, Paul, who regarded himself grasped of God to take the gospel primarily to previously un-evangelized Gentiles (‘unreached people groups’ as missiologists might now call them), would travel to a given location, typically a population center accessible by land and by sea—the likes of Philippi, Thessalonica, Athens, Corinth, and Ephesus. (As a Christ-follower and minister, Paul would also spend stretches of time in Antioch, Jerusalem, Caesarea, and Rome, all of which were ‘urban locations’. If Jesus was agrarian, Paul, we might say, was cosmopolitan.)

Upon arrival in a new location, Paul would have had to begin at the beginning (see Rom 15.17-21; 2 Cor. 10:13-16). Perhaps he, like Jesus, would win converts ‘along the way’. Be that as it may, once on the ground in a given locale, the apostle, it appears, would begin to preach the gospel and to ply his trade as a leather-worker.12 When a handful of folks in a particular place came to faith—whether through contact with a local synagogue (if there was one), where Paul as a traveling Jewish teacher would have been able to proclaim the gospel, or through conversations with an individual or a small group of people in the agora, the baths, or theaters (if Paul frequented such places), or his

12 See Ronald F. Hock, The Social Context of Paul’s Ministry: Tentmaking and Apostleship (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1980). Cf. Todd D. Still, ‘Did Paul Loathe Manual Labor? Revisiting the Work of Ronald F. Hock on the Apostle’s Tentmaking and Social Class’, Journal of Biblical Literature 125 (2006): 781-95.

workshop—an ekklēsia would be formed.13 Such fledgling fellowships (typically) met in homes, be they tenements or villas. There, it appears, believers would worship. Worship gatherings would likely have included singing, praying, prophesying, listening to sacred texts (or, on occasion, a letter from a fellow believer), baptizing, and sharing meals, not least the Lord’s Supper. When Paul was no longer able to stay in a certain location, usually due to external opposition from forces outside of the congregation, he would, as it were, “rinse and repeat” elsewhere, even though things were never exactly the same in any two places.

Popular perceptions notwithstanding, Paul was not a helter-skelter, missionary tentmaker in a holy hurry looking to drop his ‘apostolic load’ and leave. Even after spending considerable stretches of time in a place (e.g., eighteen months in Corinth [Acts 18.11]; three years in Ephesus [Acts 20.31]), he would strive to stay in touch with assemblies he started, either by visiting, networking, or writing. Paul’s converts and churches may have been out of his sight, but they were never completely out of his mind (note 2 Cor. 11.28).

A number of Paul’s letters have been preserved. In these letters there are, in the words of 2 Pet. 3.16, ‘some things…hard to understand’. Among these hard-to-understand things are certain statements that Paul makes regarding women and wives. Puzzling Pauline comments regarding gynai for which the apostle is widely, if not infamously known, include the following seven subjects: veiling heads/keeping hairdos

13 See further Stanley Kent Stowers, ‘Social Status, Public Speaking and Private Teaching: The Circumstances of Paul’s Preaching Activity’, Novum Testamentum 26 (1984): 59-82.

up while prophesying, being man’s glory, keeping silent in the churches, submitting to husbands, not exercising authority over an andros (= man/husband), being deceived like Eve, and being saved through childbirth.

This is not the place to enter into a thoroughgoing interpretation and application of the Pauline passages in which such remarks are made.14 A few brief remarks are in order, however, on 1 Tim. 2.8-15 and 1 Cor. 11.2-16 respectively, as these are the two passages where the aforementioned seven items are concentrated. Let us first consider 1 Tim. 2.8-15.15 In this text, women (or perhaps wives) are instructed to ‘learn in silence with full submission’. (Similar Pauline calls to wifely submission are found in Eph. 5.22 [note, however, Eph. 5.21!]; Col. 3.18; Titus 2.5. Cf. 1 Pet. 3.1.) Moreover, women (or wives) are prohibited from teaching and from having authority over a man (or husband). They are meant to ‘keep silent’ (cf. 1 Cor. 14.33b-36). An appeal is made to Eve as a prototype (cf. 2 Cor. 11.3). She is described as the one deceived and as a transgressor.

14 See, however, Craig S. Keener, Paul, Women, and Wives: Marriage and Women’s Ministry in the Letters of Paul (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1992), and Philip B. Payne, Man and Woman, One in Christ: An Exegetical and Theological Study of Paul’s Letters (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009).

15 Even though the preponderance of New Testament scholars regard 1 Timothy (and the other Pastorals [i.e., Titus and 2 Timothy]), not to mention Colossians and Ephesians, to be pseudonymous (= written in the name of Paul by one other than Paul), many ministers and most laypeople do not. On a practical, pastoral level, these texts are canonical and require interpretation regardless of origin. The cursory, interpretive comments offered herein should be read in such a vein.

Women/wives, then, are directed toward bearing children and managing their households (cf. 1 Tim. 5.14). It is worth noting the aberrant teaching opposed in the letter (4.1-5). One might also observe that the Pastorals Epistles assume that a bishop/overseer (1 Tim. 3.2; cf. Titus 1.7-9) and elders (Titus 1.5-6) will be men/ husbands.

The other Pauline passage to which appeal is most frequently made to subjugate and suppress women/wives in general and women ministers in particular is 1 Cor. 11.2-16. There, Paul forwards theological and ‘natural’ arguments in an effort to get Corinthian women/wives to cover their heads or to keep their hairdos up in worship gatherings. It appears that Paul is operating, at least for the sake of his present argument, with a hierarchal pattern that, at least to some extent, subordinates Christ to God, man to Christ, and woman to man. It is both interesting and instructive to note, however, that Paul does not prohibit Corinthian women/wives from praying and prophesying in the gathered assembly (note 1 Cor. 12.10; 14.1-5; cf. Acts 21.9) Indeed, Paul presumes and makes space for them to do so! Furthermore, the apostle goes so far as to posit interdependence between men and women ‘in the Lord’ (cf. Gal. 3.28). The same is true in 1 Cor. 7.2-5 with respect to husbands and wives and ‘conjugal rights’ (cf. Eph. 5.21).

Taken together these two texts (i.e., 1 Tim. 2.8-15 and 1 Cor. 11.2-16) offer a rather ‘mixed epistolary bag’, although, it must be acknowledged, that the preponderance of evidence falls on the side of restricting, if not prohibiting, the verbal contribution, not to mention leadership, of women/wives to these given congregations.

It appears, however, that no such limitations were in place, for example, in Philippi. Turning to Phil. 4.2-3, we discover that Paul enjoins Euodia (‘good journey’) and Syntyche (‘good luck’) ‘to think the same thing in the Lord’, that is, to set aside their

disagreements for the good of the congregation and for the growth of the gospel. The apostle does not enjoin these women to submission; rather, he affirms their participation as fellow strugglers and coworkers in the gospel. It is possible, though not verifiable, that these two women were among the ‘bishops and overseers’ Paul addresses at the outset of the letter (1.1).16 As I write in my commentary on Philippians, ‘[The] gender [of Euodia and Syntyche] did not exclude them from [the “work of the gospel”] any more than Clement’s qualified him for it.’17 One might note in passing that Acts highlights the ministry of Lydia to Paul, Silas, and the church in Philippi (16.14-15, 40).

Lest it seem far-fetched or as special pleading to suggest that Euodia and Syntyche held leadership positions in the Philippian church, we should be mindful of other women who served in such capacities whom Paul mentions in his letters. For example, in Rom. 16.1-2, Paul commends to the Roman churches ‘our sister Phoebe, a deacon (diakonos) of the church at Cenchreae’, a port for the city of Corinth on the Saronic Gulf. Not only was Phoebe a minister and servant-leader in her local congregation, she was also a benefactor of Christ-followers (including Paul). Additionally, it is likely that Phoebe was the courier of the apostle’s magisterial epistle to the Romans as well as its earliest public interpreter.18

Paul then turns in Rom. 16 to extend his greetings to ‘Prisca [Priscilla in Acts] and Aquila’ (v. 3). It is frequently noted that her name precedes his here (so also Acts

16 See, e.g., Carolyn Osiek, Philippians, Philemon (Nashville: Abingdon, 2000), 111-12.

17 Todd D. Still, Philippians & Philemon (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2011), 131.

18 On Phoebe and her role in the Pauline mission, see esp. Robert Jewett, Romans (Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2007), 89-91.

18.18; 2 Tim. 4.19; cf. 1 Cor. 16.19; Acts 18.2). Might it be that she was the more able or vocal of this ministerial couple? Regardless, they had connections with Paul and his mission in Corinth (Acts 18.1-3) and Ephesus (1 Cor. 16.19). Having returned to their home in Rome (note again Acts 18.1-3), Paul greets them and describes them as his coworkers in Christ ‘who risked their necks for [his] life’. He ‘and all the churches of the Gentiles’ offer them their thanks.

Romans 16 is also where Paul greets Junia, ostensibly the wife of Andronicus (v. 7). He describes them as his ‘compatriots’, ‘prominent among the apostles’, and ‘in Christ before [he] was’. Of special interest to us is Paul’s claim that this couple was ‘outstanding among the apostles’. Were they themselves apostles? It does, in fact, appear they were (cf. 1 Cor. 15.6).19 In Rom. 16, Paul also mentions the ministerial labors of Mary (v. 6), (the sisters?) ‘Tryphaena and Tryphosa’, as well as Persis (v. 12). Lastly, in this chapter, he greets Julia, who may have been married to Philologus (v. 15).

Yet, this is not all. In 1 Cor. 1:11, Paul refers to ‘Chloe’s people’. Chloe was seemingly a female Christian leader/benefactor who lived in Ephesus (or perhaps Corinth).20 In Col. 4.15, the apostle also extends his greetings to Nympha and to the Laodicean assembly that gathers in her home. Additionally, in Phlm. 2, Paul addresses

19 See Eldon Jay Epp, Junia: The First Woman Apostle (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005). Bauckham (Gospel Women, 109-222) makes a strong case that the Joanna of Luke is the Junia of Romans!

20 Gordon D. Fee (The First Epistle to the Corinthians [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987], 54) surmises that ‘Chloe was a wealthy Asian…whose business interests caused her agents to travel between Ephesus and Corinth.’

Apphia as a ‘sister’. She may have been Philemon’s wife as well as a Christian coworker in her own right. Lastly, we recall Lois and Eunice, the believing mother and grandmother respectively, of Timothy (2 Tim. 1:5).

4. Conclusion

Where does this comparative study leave us? In a pleasant, if unexpected, place. It likely comes as little to no surprise that Jesus affirmed the dignity of women, treating them as those created in the divine image, and that women played a pivotal role both in Jesus’ earthly and post-resurrection ministry. It may, however, come as a surprise to some that Paul’s calling of women/wives to silence and submission is tempered, if not trumped, by his affirmation of mutuality, if not equality, of women and wives in marriage and ministry.

Both Jesus and Paul, then, affirmed women in principle and practice. Pauline prohibitions and restrictions, I would contend, are occasional exceptions to this general rule. As such, they are contextual, not continual; time-bound troubleshooting, not timeless guidelines; a chapter in a book, but not the entire story. More often than not there is inclusion and embrace, and it is this trajectory that we trace.21 ‘Therefore, if any one is in Christ, there is a new creation: the old has passed away, behold, the new has come’ (2 Cor. 5.17). ‘For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ.

21 So rightly, Ellis, Pauline Theology, 78: “Of course, there may be practical reasons that restrict the public ministry of a woman in a particular time and place. But it appears to be clear that in principle and practice Paul affirms their ministry. Should the church today do less?”

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Gal. 3.27-28).