B. RICHTER AND THE EPIC OF URZEIT UND ENDZEIT EDEN

Sandra Richter is nothing if not forthright in throwing down the gauntlet in her book, The Epic of Eden. The Bible, she says is the story of redemption, but lest we think this study will be all narratology and no history, she also stresses at the outset that when one opens the Bible one discovers “the God of history has chosen to reveal himself through a specific human culture. To be more accurate, he chose to reveal himself in several incarnations of the same culture.” This does not lead her to suggest that God had canonized a particular culture, and called it good, nor does she suggest he should either, but she does want to insist that the eternal truths about God’s character and plan are mediated through a very specific cultural vehicle, and since, as she likes to put it, context is king, one cannot strip the enduring content from the context without distortion. Words, after all, only have meanings in specific contexts, and the same can be said of stories.

The culture out of which the OT came was, as she puts its patriarchal, patrilineal, and patrilocal. By this she means that the primary sense of identity or belonging in such a culture begins with one’s association with the patriarch, the oldest living male of the clan, and his household, then one’s larger clan, then one’s tribe, and finally one’s ‘nation’ in ever widening circles. Most important was one’s association with that inner most circle, the inner sanctum of the ‘father’s household’ where an extended family lived. The reason for repeated OT demands to care for the widow and the orphan is precisely because they did not have the necessary connections and protections of the father’s household. By contrast is the first born son, who, since he will be the next patriarch of the clan gets a double portion of the inheritance of his father. Richter sees as evidence that God critiques every culture, including these ancient patriarchal ones, the fact that in various key stories including in the story of Jacob and David, God chooses the younger son, not the first born to lead God’s people. This must have irked the ‘old man’ of the clan, on various occasions. Richter also takes Gen. 2.24 to be a critique of the patriarchal culture, for normally it’s the bride who does the leaving and cleaving. But according to Gen.2.24, the husband is to do this, thereby making plain that his relationship with his wife, not his relationship with his father, is his most important relationship going forward. In other words, Richter sees a pattern of critique of the fallen human culture and its conventions, even in the more ancient narratives in the OT. In my view she is right that Adam and Eve are indeed presented as co-equal partners in Eden in Gen. 1-2, and I would suggest this means that patriarchy is viewed in Gen. 3 as a result of the Fall, for as the curse statement says, to love and to cherish degenerates into to desire and to dominate.

At the same time Richter shows in detail that the term ‘redemption’ in the OT conjures up a very specific set of ideas involving the patriarch of a clan who puts his own resources on the line to either ransom a family member driven to the margins of society (see the story of Naomi, Ruth and Boaz), or one who has been seized by enemies against whom he has not defense (see the story of Lot and Abraham), or who has become enmeshed in a sinful life from which the person in question cannot extract herself or himself (see the story of Gomer and Hosea). Thus she urges

Yahweh is presenting himself as the patriarch of the clan who has announced his intent to redeem his lost family members. Not only has he agreed to pay whatever ransom is required, but he has sent the most cherished member of his household to accomplish his intent—his first born son. And not only is the firstborn coming to seek and save the lost, but he is coming to share his inheritance with these who have squandered everything they have been given. His goal? To restore the lost family members to the ‘bet ‘ab’ [the household of the father] so that where he is, they may be also. This is why we speak of each other as brother and sister, why we know God as Father, why we call ourselves the household of faith. God is beyond human gender and our relationship to him beyond blood, but the tale of redemptive history comes to us in the language of a patriarchal society.

Not only so, but understanding that social and historical context is key to understanding the use of the term ‘redeem’ but in those texts, and by extension in various places in the NT. What Richter is in essence arguing is that to understand the lexicon of the NT, we must read it in light of the lexicon and context of the OT. I agree with this to some extent, but this sort of reading forward into the NT has its limits, as Richter acknowledges. What she is also arguing is that God prepared for the way he would relate to us all through his Son, by means of the various ways he related to Israel in the OT. If one understands the latter, one is far more likely to understand the nuances of the NT story as well. The language is culturally conditioned, and one needs to know the culture to understand it, but God’s redemptive plan transcends one particular culture or cultural conditioning.

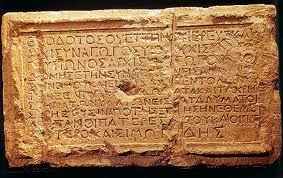

Though Richter ‘s book is not intended to be a full scale Biblical Theology study, but rather, as its subtitle suggests, is an attempt to help Christians to reclaim the OT, nevertheless she is addressing Biblical Theological matters and so her presentation merits close scrutiny.. The organizing principle for her Biblical theology, which binds the whole together is the familiar notion of covenant, and not just any sort of covenant, but in the main the sovereign/vassal covenant form, and even more specifically the form that took in the second millennium B.C. when there were both historical prologue in which the sovereign lord listed the benefits his vassal or servant nation had already received from him, as well as the blessings sanctions.

Richter finds this a crucial rubric for analyzing what is going one when the Sinai covenant involving Yahweh and Moses is described in the Pentateuch, not least because she takes the inclusion of the historical prologue (“I am the God who delivered you up out of bondage in Egypt….”) as providing evidence that even the Mosaic covenant was a covenant of grace, to which Israel must respond with obedience. This differs from the analysis of some scholars who distinguish a largely promissory covenant (e.g. Abrahamic covenant) from a law covenant (Mosaic covenant), which would explain why Paul so clearly contrasts the two covenants instead of seeing the Abrahamic covenant as leading to or even fulfilled in the Mosaic one (Gal. 3-4). Paul draws a link between the Abrahamic covenant and the new covenant, but not between the Mosaic covenant and the new covenant. In any event, she has made her point that one concept or rubric that can be used to unite the whole of Biblical theology is the concept of a covenant between an overlord and a servant (or servant people), a covenant which is confirmed or inaugurated by a sacrifice and by oaths, and which involves a prologue, a historical prologue rehearsing past benefits, stipulations, curse and blessing sanctions. With this rubric one can analyze in some detail the way God chose to relate to his people through various covenants and eras.

Richter further clarifies her view, arguing that we can tag the various OT covenants with key OT figures—Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, David.

The other interesting note that Richter emphasizes is that in a patriarchal world where people had no obligations to those not within their patriarchal circle or clan or tribe or national group, covenants were a way of creating a family sort of relationship, complete with family obligations between two parties that were not family. There is a technical term for this legal fiction—fictive kinship. Is this however the sort of sociological concept we should use to analyze why Jesus says that whoever does his will is his brother or sister (Mk. 3.31-35)? I don’t think so, and neither does Richter. Her point is that this concept made possible certain forms of covenanting, and she is right on this point.

Richter takes a text like Gen. 15 as showing the very character of God, who himself passes between the pieces of the sacrificial animal to demonstrate to and reassure Abraham that he would keep his promises, he would be faithful and demonstrate covenant love, even when the human party did fail from time to time. She sees this as a foreshadowing of Christ who presented himself as a sacrifice which inaugurated the new covenant. The important point for our discussion is that Richter sees in the OT a deliberate pattern of divine behavior revealed in covenanting that foreshadows and prepares for the ultimate covenant—the new covenant. She wants to read the Biblical narrative from start to finish, but she allows that none of it makes total since without the climax in the new covenant. We will say more about this in a moment, but here it is sufficient to say that such a front to back reading of the canon is a necessary but insufficient way to explain NT theology, as Richter, in the end, I believe would agree.

It is inadequate, as Richter agrees, because the NT writers do not see the new covenant as simply a renewal of any of the old covenants, and they do not see the various OT covenants as simply one covenant in many administrations. This is clear not only by the use of the term covenants plural in Rom. 9 and Gal. 4 but in the way Paul says Christ is the end of the Mosaic covenant in Rom. 10, and the author of Hebrews says that the new covenant has made obsolete any and all of the old covenants (cf. also 2 Cor. 3). In fact in Paul’s theology, it is in Christ that the promises to Abraham are said to be fulfilled and his inheritance is now brokered to a larger Jew and Gentile audience. Paul also says quite explicitly that the Mosaic covenant was a temporary one until the Redeemer should come (Gal. 4). We will say a bit more on this shortly.

Even just from the point of view of the sort of ancient covenants about which Richter is talking, when a sovereign/vassal covenant was broken by the vassal, the sovereign was under no obligation to do what he had originally promised if the vassal was loyal and kept the covenant. Nor was he obligated to even continue the covenant. Rather, what often happened was that the curse sanctions would usually be applied to the offending vassal and his people, and that would be the end of the covenant with that vassal. Clearly, the analogues with ANE covenants, while helpful, can only be pressed so far, precisely because the God of the Bible was a different sort of sovereign with a different and more gracious character than say for example one of the Hittite or especially the Assyrian kings. In private correspondence, Richter clarifies this: “To take this further, in reality very few suzerains upheld their end of the bargain even if the vassal WAS loyal. So I would never claim that the secular image of the suzerain is the ultimate reflection of God’s actions in redemption … but suzerain is a critically important metaphor, mostly because it is the one God chooses. I see the covenant as a metaphor in the drama of redemption much like the metaphor of parent. You would be hard-pressed to find a parent who parents as God does. But you would be more hard pressed to understand God’s metaphor if you’d never seen a parent at all.”

But the various old covenants and the Hittite lord/vassal covenants had this in common—they could be brought to an end by a serious violation, followed by curse sanctions. They were not perpetual covenants if seriously violated, unless the sovereign chose to forego the curse sanctions and the ending of the relationship, which was seldom seen as a smart political move, because one would appear inept, weak, or even not keeping one’s oath in regard to the curse sanctions. This would not do in an honor and shame culture.

In an interesting and telling exegetical move, Richter reads the story of the creation of humankind in God’s image as evidence of the pluriform nature of the deity. She says “Note the deliberative plural: ‘Let us make…in our image…male and female he created them’ (Gen. 1.26-27). It seems that the plurality of humanity (male and female in relationship) reflects the plurality of the original; and humanity like deity, is created to live in relationship.” I myself would take the ‘let us make’ as a reference to God speaking to the heavenly council of angels and Richter discusses this very possibility later in the book Richter is right that the fact that the image of God in humankind is ‘male and female’ and so plural in Gen. 1 does suggest that if the image truly reflects the original, that God too was pluriform in some way. This in turn makes better sense of the NT teaching about Christians being conformed to the image of the Son (Rom. 8.28-30), a particular member of the Trinity.

Richter, in addition, sees Gen. 3.15 and the promise to Eve that her descendent will crush the head of the serpent, as a foreshadowing of the role of Christ in his cosmic battle with Satan. In addition to this she sees the sabbatical pattern of the week, six days of work, one of ‘rest’, as revealing that our lives are not meant to be all work. Humans were made for both work and rest, both labor and worship. She sees the driving of Adam and Eve from Eden as the driving of them from God’s presence. They were no longer fit for either a perfect creation or a perfect relationship with God. There were to be labor pains for both Adam and Eve, though in different senses. And she adds “when we ask the salvation question, what we are really asking is what did the First Adam lose? And when we answer the salvation question, what we are really attempting to articulate is, what did the Second Adam buy back?” In other words, she sees the Genesis stories as foundational for understanding redemption and what human life was to be restored to ultimately. She follows the lead of Paul in the way she will put together the pieces of the tale of creation, fall, and redemption.

There is more however. Richter emphasizes the cosmic effects of Adams sin— the whole world fell with Adam, and not just humanity. The irony, as she puts it is that while humans were created to subdue the earth, now a fallen rotting earth will subdue each one of us when we die, are laid to rest, and become fertilizer. The earth creature (which is what Adam means), will be swallowed up by the earth it has corrupted, which is poetic justice if there ever was any.

How would God begin to affect reconciliation with his estranged and fallen children? Richter sees one major stage as the establishment of the tabernacle as a place for God to dwell in the midst of his people noting Exod. 25.8—“let them construct a sanctuary for me, that I may dwell amongst them.” But this would be an isolated spot, and unlike Eden, this sanctuary would not be for human habitation, indeed only priests would be able to enter into the divine presence. Otherwise human beings had to stay in the outer court where the sacrifices would be made. In an interesting move, Richter sees the reference to the angels on the curtains shielding the Holy of Holies, as like the cherubim who fenced off Eden to prevent re-entry by a fallen Adam and Eve. And further she sees the cherubim on top of the mercy seat on top of the ark of the covenant as protecting God from defilement, and, I would add, perhaps also the priests from God’s deadly powerful presence. A fallen person cannot come close to a holy God without serious consequences. God is envisioned as sitting above the cherubim with the ark as his footstool. The tabernacle, like the later temple then has Eden motifs in it, meant to remind and turn the heart of the believer back towards Eden. But that is not all. The next port of call is Ezek. 47, part of Ezekiel’s vision of the restored temple. She focuses on Ezek. 47.8-12 where we hear about a river which flows forth from the throne room of the Holy of Holies and goes out and transforms the Dead Sea into a living sea, but more tellingly this river produces everlasting trees which continually bear fruit and support life. She sees in this an echo of the tree of life in Eden. Not surprisingly she connects this to the material in Rev. 21-22 stressing that there is no temple in the new earth because there is no reason to house God or fence God off from a no longer fallen world or fallen humanity. The outpost of God in a fallen world—tabernacle or temple, has become the whole, but not without a return to Eden.

Richter acknowledges that of course the final vision is of a city the new Jerusalem, and there is nothing about a city in Gen. 1-2, though the city in Rev. 21-22 certainly has a garden. She also stresses there are no cherubim in the new Jerusalem as there is no need to protect the ruler, or those ruled either. But then why are their angels in heaven in the new Jerusalem above, worshipping God according to this same book of Revelation? This question is especially pressing since John’s vision is that heaven in the form of the new Jerusalem will come down and affect a merger with earth. If there are angels in heaven where the new Jerusalem now is (see e.g. Gal. 4) then it is reasonable to expect them to be in the new Jerusalem on earth as well. Richter’s explanation is that while angels and cherubim are both in the general category of divine beings, that the cherubim are of a different class than ordinary angels. She says angels and cherubim are not equated in the OT,

More convincing is her comment that the essential plot line of the Bible, after Gen. 3, is – How do we get Adam back into Eden? The bulk of the Bible is seen as the tale of the rescue plan to accomplish that intent. All God ever wanted was for those created in his image to dwell forever in his presence in a holy paradise, enjoying God forever. Richter rightly stresses that the finish line in the Bible is never ‘dying and going to heaven’. It is rather heading for the new Eden the new Jerusalem which transpires after Christ returns, the dead are raised, and the kingdoms of this world become the kingdom of God once and for all. This is unsurprising since human beings are earth creatures—flesh and bone.

It follows that a material place would need to be the finish line for this sort of creature. We are not angels. Thus heaven comes down, and there is a return to Eden for the earth creature in the end.

Richter then seeks to make sense of God’s making a series of covenants leading up to the new one. She says, in effect that redemption is presented to us as a series of steps, a series of covenanting acts—with Noah, Abraham, Moses, David and finally the new covenant. She argues that in God’s design what had to be accomplished would not all be accomplished in one fell swoop. The goal was the people of God dwelling in the place of God enjoying the presence of God. The Noahic covenant re-established contact between God and humankind and speaks to all of creation. The Abrahamic covenant reestablished the relationship such that there is a people of God, dwelling in God’s place (the Holy Land). The Mosaic covenant begins to reestablish the last bit of the equation—God dwelling in the midst of his people. This covenant typologically fulfills the promises to Abraham, but only typologically. The Davidic covenant then adds “the capstone of a human leader whose first ambition is to lead his people in their service to God. David is, in essence, the ideal vassal.” He becomes the prototype of the messiah/ Christ.

The covenanting progression moves from a covenant with one man (Noah), to one family (Abraham) to one people or nation (Israel) to all people (the church). “Each of the stages in the story brings Adam one step closer to full deliverance; each serves to reeducate humanity as to who the God of Eden really is.” In Richter’s vision, the Fall had such devastating intensive and extensive effects on Adam and all of creation that the redemption plan took several stages climaxing in Jesus and the new covenant, but not complete until the new Jerusalem at the eschaton. It is clear that for Richter Rom. 5.12-21 is a, perhaps the most crucial of NT texts for her overall schema of Biblical theology. Jesus is Adam gone right, the one who was born sinless like Adam but resisted temptations unlike him and she sums up as follow: “when he chose to participate in the crucifixion by taking the wrath of God upon himself on our behalf, he did two things. One, he proved the first Adam could have succeeded in his charge. Two he bore in his own body the curse of Eden, so that the children of Adam would not have to. And when Jesus rose from the grave, he defeated death; he eradicated the curse of Eden. And because Jesus was both human and God, his death and resurrection was of such a nature that it could be vicariously applied to all of Adam’s children.”

This sort of reconstruction however raises several questions: 1) was redemption really delivered in stages, covenant by covenant, or only by Christ in the new covenant, and if it was the latter then; 2) why did we need all those other covenants? Why not just go from Adam to the last Adam and spare the world millennia of misery? In response to the first question she says “This of course is a complex question. Redemption is presented to us “stage by stage” in the biblical narrative, but we are also told that Christ was slain before the foundation of the world (Rev 13:8) … so there are in actuality no stages.”

In terms of her modus operandi, one tool in her arsenal is that Richter uses what is typically called catchword connection. So for example the use of the term tebat(ark) of the vessel Moses’ is put in when he is set loose in the Nile is seen as “an obvious and intentional association with Noah’s tebat” I’m not so sure the connection is obvious since, so far as I can see, tebat is not a technical term. Richter has a very high view of Scripture, and she assumes that nothing is there by accident or chance.

While I agree that this is so, one of the problems with catchword connections of texts which otherwise don’t have a connection is over-reading the text. There is no flooding of the Nile when Moses is put into it, and he isn’t being rescued from water, but rather from a death edict by a wicked human being. The mere presence of water in the two texts is not enough to warrant pressing an analogy. I do agree however that in view of the Hebrew’s fear of the chaos waters and the story of the flood, it is an obvious connection to see in Rev. 21.1 the final defeat of a formidable foe that had often troubled humankind, including Noah, Moses and the Israelites at the Red Sea, Jonah and others.

More promising however is the fact that Richter believes that typology is the basic hermeneutic which helps us relate the OT to the NT, the old covenants to the new one. As she points out a typology involves two sets of historical events or persons or institutions or even places which are compared in some way. The idea underlying this is that God’s character is consistent and so God acts in ways in earlier eras of salvation history that foreshadow the way he acts in later eras. But

Richter wants to stress that “a type operates upon the principle of limited fulfillment.” She draws an analogy between a model airplane and a real one. Both are planes and both can fly but the model plane cannot carry the same freight as the real one. So she sees the comparison first and last Adams as a form of typology or the comparison of circumcision and baptism as a form of typology, or we could suggest Melchizedek and Christ as an example of a typology focusing on someone who is a priest. Typology, unless the comparison is between two persons, events, places or institutions within the OT is an exercise in cross-testament Biblical theology, which is precisely what Richter is doing in her book. One would never guess circumcision was a mere foreshadowing type, or the OT temple was a mere foreshadowing type or Adam was a mere foreshadowing type if there was no NT. In other words, this is reading the OT in light of its fulfillment in the NT, a fulfillment that transpires in various ways. Now the undercurrent of

Richter’s presentation is that the events, institutions, persons in the OT are preparatory for what we find in the NT, prefiguring and preparing for them. Again, this is a specifically Christian theological way of reading the OT, a way that many Jews would find objectionable since they don’t accept the NT as the further adventures of Yahweh, which is of course why the book is subtitled ‘ A Christian Entry into the Old Testament’.

When it comes to the tabernacle, Richter takes this as not merely the sign, but the evidence that God had taken up residence with his people once more, however “the double-edged sword of the tabernacle was the truth that God was once again with Adam but Adam was still separated from God.” Hereby was made clear that Israel had not been cleansed from all sin and atonement still needed to be made repeatedly clean, and even then only the high priest once a year could dare venture into the living presence of God without getting zapped (see Lev. 16.2).

Richter here stresses that what is going on in the OT is not mere-shadow boxing or play-acting, or mere symbol. She puts it this way “important as we think about the nature of types and typology is the fact that the tabernacle did provide some level of atonement for God’s people (Lev. 1.1-4; 4.35). It was real. It was effective. It was historical. But like all types, it provided limited atonement.”

But what is the function of an inadequate type that does not really, or at least does not fully, do the job it is meant to do? Richter’s answer is that it has a pedagogical function as much as anything else, and thus in fact it does do what God intended it to do. Because of the type, all God’s people are educated in the need for atonement, the need for mediation and a mediator, the need for a final and ultimate sacrifice.

And the mission of atonement is necessary so that God can and will permanently dwell with his people. Now again, this of course is a Christian reading of these OT institutions, an exercise in Biblical theology which wishes to preserve some viability, some unction in the type, while still insisting that the antitype is where the real, complete, final, fulfilling action is. By this means, the OT is recovered partly for Christians as a pedagogical tool which helps them understand the nature of God and the NT.

Richter goes on to suggest that what Hebrews 10, and various Pauline texts indicate is that the OT law, while a good and godly thing, could not enable fallen persons to keep it. The Law only foreshadowed and instructed about the good things yet to come in Christ, but until God came and dwelt within his people individually, not just in their midst, their hearts of stone would not be transformed into hearts of flesh, and Jer. 31.31-33 would not be fulfilled and fleshed out. At a crucial juncture in her argument, Richter follows the suggestion of Scott Hafemann and others that the new covenant is not really a ‘new’ covenant which has a ‘new’ law, as the problem was not with the law of God but rather the people of God, and so Jer. 31 is indeed talking about the Mosaic law being renewed and applied to God’s new covenant people.

The problem with this suggestion is that it fails to do justice to what Paul actually says about the Mosaic Law in 2 Cor. 3, Romans 10, Gal. 3.-4 and elsewhere, never mind what the author of Hebrews says. The Law was not a mere tutor according to Paul. A paidagogos is a slave guardian, and there are problems with such guardians if they overstay their time period. Their job was only to help the child of a well to do person rehearse their lessons when they came home from school, and keep little Publius in bounds and safe going back and forth from school.

The paidagogos was definitely not the primary educator or tutor.

Paul is quite clear that when Christ came he came to redeem people out from under the Mosaic Law, because there were problems with this Law, not in intent but in effect: 1) it was impotent. It could not enable fallen persons to keep it, and so as Paul says the effect of the Law is that it turned sin into trespass, and condemned the fallen person. It ended up being death-dealing rather than life-giving though of course that was not the intent of the Law, which was good in itself; 2) as the author of Hebrews stresses, the big problem was the inability of the Mosaic law to in any way cause the new birth or transform hearts. It could only produce outward not inward change at best, hence the need for the covenant Jeremiah had in mind. The real problem with the Hafemann approach to Biblical theology is that it over-emphasizes the continuity between various of the old covenants and the new one, specifically when it comes to the matter of Law.

In any case, Paul indicates in Gal. 6, there is a new sheriff in town when Jesus appears, and he offers a new law—the Law of Christ, which we have talked about at length in this two volume study. Richter concludes her discussion of the Mosaic Law by suggesting that in fact Jesus in his critique of the Pharisees and Saducees is probably partly critiquing Jewish halakah or haggadah, the traditions of the Pharisees built up to provide a fence around the Law. I think there is some truth to this, but it is not the full picture. Jesus believes he lives in the eschatological age of fulfillment, and both the OT Law and the prophets are being fulfilled in him, and once fulfilled they become obsolete. Of course the Law and prophets remain, and should remain until all is fulfilled, not least because they are still valuable for training in righteousness as 2 Tim. 3.16. puts it, but laws no longer need to be obeyed if they have been fulfilled and their purpose has been served and their usefulness completed.

But talking about fulfillment is a different matter than suggesting that Jesus repristinizes the old covenant or the old law, and Richter is careful not to suggest the latter. Jesus acts in relationship to that law with the sovereign freedom of one who came to give a new Law—sometimes he reaffirms old commandments, sometimes he intensifies them, sometimes he offers entirely new commandments, sometimes he abolishes old commandments. This is because he is indeed inaugurating a truly new covenant, not merely renewing an old one.

This is also why Paul speaks of covenants plural and sees the new covenant as the replacement for the Mosaic one, and the fulfillment of the Abrahamic one.

To her great credit, Richter realizes the difficulties I have been pointing out and in a supplemental clarifying discussion at the end of her study she says that she is not certain how things should be adjudicated (though she is sure the old ‘ritual/political law is abrogated, moral law of Moses is continued’ distinction does not work). She tentatively suggests, “And for all the Mosaic law, be it superceded or not, we need to recognize that we can (and must) still learn a great deal about the character of God through these laws, even if we can no longer directly apply them to ourselves in this new covenant. So rather than thinking in terms of the Mosaic law being obsolete except for what Jesus maintains (as has been the predominant view), perhaps we should begin to think in terms of the law being in force except for what Jesus repeals.” The problem with this suggestion is it leaves Christians obligated to an awful lot of OT laws that are not reaffirmed in the NT, laws for example laws about tithing. It is better and safer to say that only those portions of the law which are reaffirmed in the NT are Christians obligated to obey,

The final piece of the OT puzzle is put in place by the Davidic covenant, for here, in texts like 2 Sam. 7 we see the beginnings of messianism, the promise of a kingly dynasty from the shoot of Jesse. What is needed is a human but royal representative who not only leads but stands as mediator between God and his people. From here it is easy to see a straight line to Jesus, who is presented in the very first chapter in the NT as the son of David, but also as the son of Abraham.

Having gotten up a considerable head of OT steam, connecting the six covenant with six key figures (the last of course with Jesus), Richter brings the full weight of this paradigm to bear on her interpretation of Jesus when she says: “Jesus is prophet, priest, and king. He is the last Adam who defeats Eden’s curse; the second Noah commissioned to save God’s people from the coming flood of his wrath [see 1 Pet. 3]; the seed of Abraham; the new lawgiver who stands upon the mountain and amazes his audience by the authority with which he speaks; and he is the heir of David.”

Looking for other connections with the OT, she presents John the baptizer as the last prophet of the Mosaic line, who nevertheless uses the sign of the new covenant to identify the new king, who is promptly anointed by God, not the prophet, and God makes the coronation announcement to the king, calling him Son (see 2 Sam. 7). Here she sees a period of overlap of the old covenant and the new covenant. The problem with this interpretation of the baptism of Jesus is that later in the NT it is made clear that John’s baptism of repentance is not the sign of the new covenant, and those who have received it need rebaptism (see Acts 18-19). Equally interesting, but debatable, is her connection of the tongues as of fire and the wind in Acts 2 with Exodus 40 and 1 Kngs 8, pointing out how the tabernacle and temple were inaugurated with cloud, fire, wind. Her point is that God has come in person to dwell ‘in’ his people who become his temple or tabernacle. The point of all this is to make the case for the OT being the Christian’s story. I would put it rather different. The OT is not our story since most of us are not Jews, but it is a story into which, as Paul puts it, we Gentiles have been grafted through our Jewish messiah Jesus when we became ‘in Christ’. We are not by nature the children of Abraham, but we have become his adopted heirs, through Christ the seed of Abraham.

There are many merits to Richter’s approach to Biblical Theology. Unlike too many Christian attempts at this, she in no way neglects the OT, which one would not expect anyway since she is a OT scholar. If anything is given too slender a treatment, it is a detailed reckoning with the NT and the way the NT reconfigures the nature of the discussion of theology and ethics as well, but then her book was intended as a Christian entry into the OT, not a full Biblical Theology. She is to be commended as well for not compromising or neglecting the historical nature and givenness of the OT text in her theologizing. She does not allegorize the OT, nor readily over-read Christian concepts back into the OT. She confines herself to patterns, word connections and typology which do not vitiate the historical character and development of the story of God and his people.

Also to be commended is the way she very skillfully presents a narrative theology which encompasses the whole canon, not merely by talking about creation, fall, and redemption, but by giving good and detailed discussion of all the OT covenants. We could have used much more discussion of the new covenant, especially in regard to the issue of continuity and discontinuity between the various old covenants and the new one, but that is surely a task for a further study.

I could have wished for at least a recognition that what the NT writers mean by salvation is rather different from what is meant by redemption in the OT. Though there is often common vocabulary that the two testaments share, they are operating with different lexicons and meanings at various points, not least because the OT says precious little about a theology of the afterlife, and even less about a theology of the other world and also because the cultural context of Jesus is in important ways very different from that of the previous five covenants and major covenant figures. Richter does recognize that what kingdom means when Jesus says it has come in his ministry, is something rather different than what kingdom meant on the lips of a Saul, David or Solomon. Those kings were not envisioning God ruling directly, but the Dominion of God Jesus has in mind indeed involves the direct divine saving activity of God from above transforming people from the inside out, and recreating the people of God, almost from scratch.

I must end by saying that Richter’s effort is a very good beginning for a genuine Biblical theology. It is in many ways the clearest, succinct, helpful attempt I have encountered and it gives me hope that Biblical theology can be done in responsible and helpful ways by Christians. I find nothing major lacking in the way Richter reads the canon from front to back. What is lacking is a more profound reading of the canon from back to front, for the NT writers reasoned over and over again from solution to plight, not the other way around. By this I mean that once they had fully grasped the surprising nature of salvation through the coming, the death, and the resurrection of that Son of Man, (something early Jews were certainly not looking for), this caused them to go back and re-read their Scriptures with new and more Christological lenses. It changed the way they evaluated all those OT covenants, and even changed the way they view major figures like Adam, Abraham, Moses and David. Perhaps only when there is a co-operative venture between OT and NT scholars will a Biblical theology emerge that does full justice to the need to read the canon both front to back, and at the same time eschatologically and so back to front, the latter being, in my view, the more crucial hermeneutical move. Indeed the latter is the hermeneutical move we see the NT writers making again and again. In the end however, Richter has done us a great service in reminding us of the epic of Eden, and how we need to get there by going forward to the end, not by going backwards to the garden paradise.