Fellow blogger and sociologist Mark Regnerus’ recent post on suicide rates and ideation prompted me to reflect on suicide in parts of Asia and in Asian America from the news I have been reading of late. Perhaps the most notable is the one that showed up in the New York Times citing an unprecedented increase in suicide among elderly Korean women. As the article suggests, some of this is prompted by the structural changes in Korean society that have not been adapted by all members of society due to the cultural differences brought on by structural changes. In the US, our social security system is a kind of broad social contract between generations of working Americans. Regardless of ethnicity, religion, etc. workers in America help cover some of the expenses for the retired. In Korea, the contract is more specific to the family: children, usually sons, are expected to provide the economic safety net for their parents directly. Put differently, earlier generations invested in their children with no private savings set aside for them. Thus, when we combine the other demographic dynamics in Korea (i.e. declining marital and fertility rates) we have a recipe for disaster; while the standard of living in South Korea is incredibly high, the benefits of that improvement have not resulted in unilateral better retirements for the elderly. If we follow the traditional logic, the fact that many elderly feel abandoned suggests that the highly prosperous working generation no longer feels obligated to assist their parents or perhaps they cannot do so while maintaining a new and higher standard of living. We could also ask why the government is not stepping in and supporting these elderly. According to the article the government safety net was only just recently developed (1988) and is apparently inadequate in day-to-day coverage of expenses. And there are these cultural loopholes in this system where adult children deemed “capable” of providing support to parents locks out access to social security to those elderly. In such situations (and apparently it’s growing more pervasive), many elderly Koreans find no other recourse but to take their lives when their children cannot (or will not) help, and the state fails as well.

It turns out that this trend toward elderly suicide is more complicated for Asian Americans. According to this mini-guide on the basics of suicide, the Asian American rate is lower than other groups in general. But the picture is mixed for the elderly. According to this graph from the Centers for Disease Control, elderly white non-Hispanic males commit suicide at a much higher rate than men of other groups, including Asian Americans. However, among elderly women, Asian Americans are more likely to commit suicide than any other group. Asian American elderly men are still more likely to commit suicide than women, but it’s noteworthy that suicide attempts are higher for women here. The question remains: why? What might be at work in the lives of elderly Asian American women that increases the likelihood of suicide? One wonders if it is a similar sense of felt abandonment by their children, many of whom managed to be very successful materially.

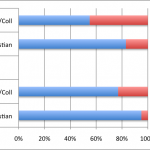

Since the CDC does not provide demographic information on suicide ideation, planning and actual attempts, we can turn to research by social scientists in their paper published in the Archives of Suicide Research. There they found that among Asian American adult respondents, women more often reported attempting suicide compared to their male counterparts (3.5% v. 1.5%). Most strikingly, US-born Asian American women reported a much higher attempted suicide (compared to men, both US born and immigrant), suicidal planning, and ideation compared to immigrant Asian American women, US born Asian American men, and immigrant Asian American men. When the researchers account for other possible factors that influence suicidal thinking, they find that US-born Asian American women are significantly more likely to report suicidal thoughts compared to their male counterparts. Still a glance at the effects shows that while the differences aren’t significant statistically-speaking, there is a clear gender and nativity dynamic at work.

If suicide ideation results in part from stressful conditions, one would think that immigrant women would feel more stress and consequently be more prone to suicide ideation. The researchers suggest that the higher native-born suicide ideation rate may be a result of socio-political factors such as gender trauma, racial trauma or some combination. A year after this study was published, social scientists Janice Cheng and associates used the same data to examine this very possibility. They confirmed that racial trauma (defined as perceived discrimination) along with gender (that is, being female), family conflict and depressive symptoms contribute to Asian American suicidal ideation. Put together, these two studies suggest that native born Asian American women struggle not only with their minority racial status but also their particular position in their families. If most elderly Asian American women are immigrants, then we have a gendered multigenerational problem: both the immigrant elderly and their native-born daughters struggle with suicidal ideation. And while separated by the Pacific, today’s elderly in Korea are perhaps similar to the elderly Asian Americans in that their strategies for survival were built on assumptions that are not shared by their children who have succeeded in contexts that reward individualistic attitudes. The adult daughters in these contexts face similar dilemmas in making sense of the expectations ingrained at an early age from their parents and the world of their peers. Perhaps it’s not so surprising then that family conflict is linked to suicide ideation for Asian American women. Hopefully, these kinds of studies are reaching the right ears to aid Asian and Asian American elderly women find meaning and belonging in a world that has restructured right before their eyes.