…the distribution of the castes in the city exactly follows the march of the annual cycle, which normally starts at the winter solstice. (Guenon, 2004, p. 97)

The origins of the Castle in the witchcraft of northern Europe incorporates the spectacular mythologies of the Grail, Celtic legends, medieval Christian mysticism, and the most ancient cosmological systems. An oft misunderstood concept, the Castle informs a large part of Traditional Witchcraft since the 1960s, made popular perhaps through the subsequent publishing of the works of Robert Cochrane (1931 – 1966). During a talk on the witches’ compass at Treadwells, London, in 2016, Stuart Inman of the 1734 tradition was asked by the host about the significance of ‘castles’ in such philosophies of witchcraft. This simple question reveals a significant divide between those of us who use such perspectives and those more aligned with popular occultism and modern Wicca, where a castle might more readily be seen to represent a symbol of violence and oppression. Of course, its origins lie somewhere in the magic and mysticism of the distant past, filtered through diverse cultural influences, coalescing in the medieval romance tradition and arriving, finally, in our collective cultural mythology and folklore.

Surprisingly, the perennial philosopher of the Traditionalist School, René Guénon (1886 – 1951), begins an essay upon the The Zodiac and the Cardinal Points with a discussion about the arrangement of ancient cities within a fourfold pattern that incorporates a division of social groupings, sometimes called a ‘caste’: “usually each cardinal point is matched with one of the elements and one of the seasons, as well as the colour emblematic of the caste situated at that point” (Guénon, 2004). Much of this will sound familiar to occultists who are informed upon magical correspondences since the demise of the Golden Dawn and the associating of each of the cardinal compass points with a Classical element, season, and even colour or wind (the airts compass of Celtic systems). What many will balk at, however, is the suggestion of the outmoded caste system which debase and subjugate the lower echelons in favour of a perceived elite. However, there is much to learn in this as cosmological map which is hinted at in Guénon’s essay. Indeed, it is a means to learn more of the Castles which lie at the heart of the modern traditional witch system and compass.

Etymologically, the words ‘castle’ and ‘caste’ find a common origin in earlier Proto-Indo-European *kas, signifying ‘to cut’. Although moving through Portuguese casta, meaning more appropriately ‘tribe’, the root word which gives us ‘caste’ is the same which indicates ‘castle’. The relationship between the two words is convoluted and historical nuance informs how we respond to the words today, but the symbolic and cosmological source gives us much to think about in the context of our study. With regard the root word, *kas, meaning ‘cut off’, we can see a common source for both ‘caste’, as in separated or ‘cut off’ from other adjacent tribes or groupings, and ‘castle’, which is often physically distinct from the land around and which is not it, to delineate or demarcate land and mark it out as sacrosanct.

In its original form, a castle was a village or town, a collection of connected dwellings where a tribe or people reside and carry out the social actions of a cultural body. The Latin which gives us the sense of fortified encampment, or martial structure, originates place names such as Chester, from castra. Of course, as cultures advanced and encroached upon each other, evolving through proximity to neighbouring tribes, the imperative to fortify and defend the communal homestead would develop into boundary walls, indicating a sense of ‘us’ and ‘not us’, and would escalate into battlements intended to repel invaders. This later development informs our idea of the castle today, but it wasn’t always so.

The need to distinguish the cultural hub and homestead of the tribe, however, was always present and the cutting of the land to indicate an enclosure was necessary for civilisations in most mythological origin stories. Indeed, we are told that the earliest city-builders ploughed a ditch around their city, as in the myth of twins such as Romulus or Cain, for example. Of course, this evolves the sacred enclosure, temenos, which is separated or cut off from the mundane and profane outside. The sense of the inner and outer would reach a mystical peak for the wider European awareness through the work known as the Interior Castle, written in 1577 by Teresa of Ávila, a Carmelite and mystic nun. The symbolism of the Interior Castle draws powerfully upon the identification of the inner (as distinct and ‘cut off’ from the outer), where the Castle represents the soul and its seven mansions which are achieved through prayer, virtue, grace and mystical practice; similar to the Merkabah tradition of Kabbala which gives us the Hekhalot system and informs both books of Ezekiel and John of Patmos’ Book of Revelations as visionary devotional works.

Importantly for family and clan based traditions of witchery, the Castle represents a place of gathering for its members; the tribal home, hearth and centre, where both corporeal and discarnate ancestors may meet. In this way, it is perfectly aligned with the meaning of a town, village, the enclosure of the tribe or family, separated from the wild, or mundane, deemed ‘outside’ of the demarcated space and time. Furthermore, folk tradition and medieval romantic symbolism has woven an otherworldly aspect to the castle, identifying it as that which is difficult to obtain and houses an esoteric treasure – the Grail itself.

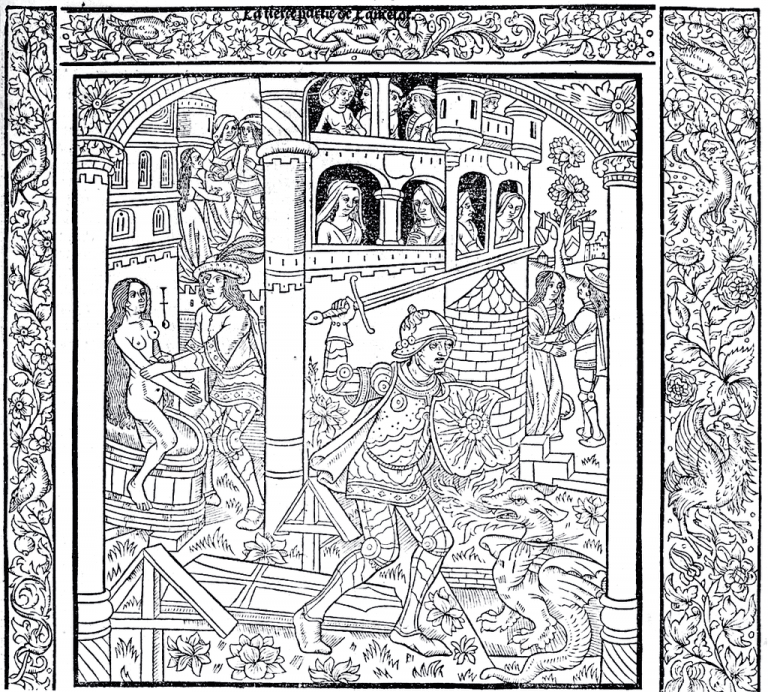

Representing spiritual attainment (Cooper, 1992, p. 30) the Castle often contains a boon, such as the Holy Grail, and often an imprisoned person who has relevance to the individual – an ancestor, lord, princess, bride, or mother. The quest for esoteric knowledge, too, is symbolised within the Castle, and the Bridge, therefore, is often included within the mythic landscape which precedes the attainment or testing of the Castle proper. In some instances, an opponent, such as with the rex nemorensis, must first be overcome in order to gain access or initiation into the mysteries of the Castle. In order to pass the guardian or Castellan, certain requirements, including familial adoption or vouching, must be fulfilled before the Castle is won. In other incidences, the Castle is assailed as in the Middle Welsh poem from the Book of Taliesin, Preiddu Annwn, or Spoils of the Otherworld, which recounts a raid upon the otherworld Castle led by King Arthur and with similarity to the invasion of Ireland by the British King Brân. For the medieval Grail hero Percival, it is the Castle of the Souls, Corbenic, and the mysterious Castle appears infrequently and in visionary form when the aspirant is prepared. Furthermore, the correct question must be asked once the interior is gained, demonstrating the enquiring mind which is the only sure way to win the mystical and esoteric wisdom contained within. Corbenic, the home of the Fisher King, keeper of the Grail, is reminiscent of a proto-fisher king, Brân the Blessed, also called ‘pierced thigh’, who is the Raven (or crow, corvus) King.

Much of this discourse is prompted by the regular returning to a document written by the late witch magister Robert Cochrane which often turns up in reference, or full, in 1734 and related witchcraft discussions. Known as The Basic Structure of the Craft, this piece outlines a cosmological map proposed by the writer, usually assumed to be Cochrane and his wife, which includes four castles standing at the cardinal directions. Each is ascribed a ruler, or king, and the domain described with some detail pertinent to the four castes outlined in Indian and similar civilisations’ cosmology. As we have seen, this same model might be thought to refer to the tribe, type or ‘caste’ which presides over the nature of each of the directions, moving through the annual cycle of the seasons.

Symbolised by the square, it [caste] is the pattern of the universe; the pairs of opposites; the four cardinal points which, in turn, are connected with the four seasons, elements and emblematic colours. (Cooper, 1992, p. 30).

In occult lore, then, the Castle is four-square, yet encircled. It is enclosed, containing the familial and tribal ancestors, the essence of the socio-magical culture at its spiritual hearth. It is aligned to the cardinal and inter-cardinal compass points, cosmological watchtowers, as well as the seasons of the year. Finally, it is measured with the castes, peopled by the embodied expressions emblematic of the mythological character which comprise the lands of those compass points, fixing the axial Castle at its heart.

Bibliography

Cooper, J. C., (1992). An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols. Reprinted. London: Thames And Hudson.

Guénon, R., (2003). Symbols of Sacred Science. English Trans. of 2nd French Ed. New York: Sophia Perennis.