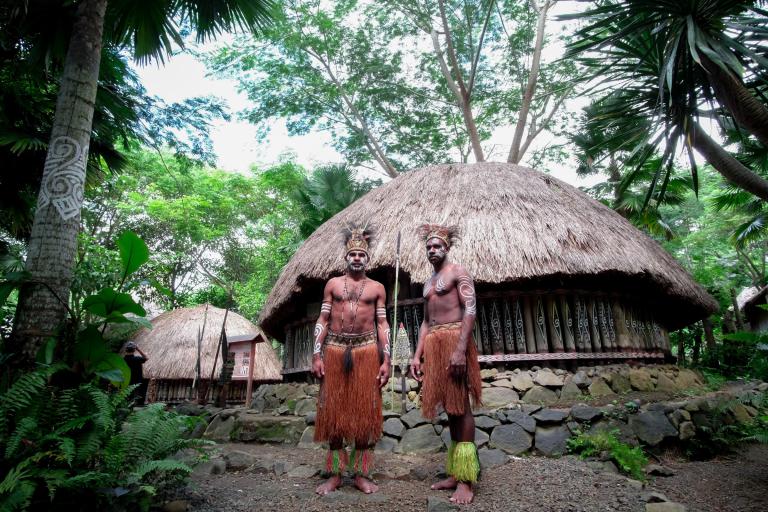

Within the milieu of neopaganism, and nature-based religious movements that lie at the heart of modern Wicca and Druidry, as well as the magical arts in a broader context, the ancestors holds high office. When we talk of ancestors, most frequently we are thinking purposefully and immediately of deceased familial groups, past family members and direct lineal predecessors who now occupy the space of spirit. Indeed, there is a persistent regard for such ancestral notions in the Western world, through Catholic prayer, as well as in dominant Eastern traditions such as Taoism and Shinto.

Veneration of the dead has occupied a central place in the the ceremonial and ritualised traditions of human thought and belief for millennia, perhaps since the dawn of consciousness itself. Indeed, it has been noted that intelligent animals, such as crows, possess an awareness of death and enact ritual and superstitious behaviour regarding the dead. It has been suggested that this is, perhaps, more to do with evaluating risk, which may be the origin of funerary behaviours in all species, but the remarkable intuition and awareness of death indicates that the bare root of the concept is not lost on our animal kin.

Whilst watching the fantastic documentary film Tawai, from adventurer and indigenous peoples advocate Bruce Parry, something an Anthropologist said struck a important chord with me. In a discussion of the egalitarian societies of the Penan people of Borneo, a hunter gatherer society whose way of life is under threat from logging companies and the political machinations which encroach irreversibly upon their land, talk of ancestral society comes up. The symbiotic relationship with the forest, which is structurally essential to the Penan’s identity and worldview, is an extension of their egalitarian perspective which does not include concepts of time and possession. Both of these notionally arise after the shift to an agricultural way of life which depends upon apprehending seasonal time and the hoarding of property, together with its subsequent protection and raiding in times of need. It is thought that the Penan, and some few fellows in Indonesia and parts of remote Africa, are among the last of these hunter gatherer societies with such a worldview.

In the discourse on ancestors, however, a couple of thoughts immediately spring to mind. The first is the animist sense of spirit that such people possess, relating to their worldview and the awareness of everything as coexisting in a relational sense to each other. As part of a broader panpsychism, such an animistic outlook perceives the rainforest, and its abundance of life, as a quintessentially living, breathing, vital part of the world of which the Penan themselves are just a part. In this respect, the entire rainforest is ancestral to such a peoples.

In another documentary film, Hadza – The First and Last, the semi-nomadic hunter gatherer Hadzabe people of Tanzania allow anthropologists into their lives to learn more about their remarkable, ancient society. Having remained largely unaffected by outside influence, the Hadza have survived in their homeland for an estimated 50,000 years or more. Like the Penan, their way of life is also under threat and the viral cancer of modern society, with its materialistic, economic and social attitude invading in the most egregious manner.

One of the extraordinary details of the Hadza cosmology is that they don’t appear, to early anthropological studies, to have a belief in the afterlife. On the contrary, theirs is a complex and rich cosmological model that is thriving and vibrant, with rigorous ritual and an awareness of the innate inequality that is inherent with material possessions as a source of dependence upon a sense of physicality. The truth of this latter is nowhere more evident than our own lives and we need only think for a moment about the value we place upon our own possessions, and how those make us feel inferior and superior within a broad social structure.

An article by Thea Skaanes, Notes on Hadza Cosmology – epeme, objects and rituals, discusses the virtue of spirits and ritualised objects at length. In this fascinating study, we learn that the Hadza acquire their spirit through the ritual of naming, the name itself being possessed of the spiritual quality and nature. Further, the relation between the living and the dead women of the tribe is expounded:

The a’untenakwete-gourd is ritually a non-human instance of the woman herself and the oil it contains is powerful and used only in rituals… During the monthly night-dance rituals, a dancer might dance in the name of a family member’s a’untenakwete-gourd as the potent evocation of the family member herself. Even after her death, the dancers might dance in the name of the gourd to evoke the dead woman’s spirit to the site… Dancing in a dead woman’s name without the mediating gourd will evict her spirit from a proximity to the living, and this is a course of action taken if a recently dead person’s spirit is occupying the minds and dreams of relatives.

Skaanes, Thea. (2015). Notes on Hadza cosmology. Hunter Gatherer Research. 1. 247-267. 10.3828/hgr.2015.13.

The relationship with the ancestors, then, occurs wherever we encounter the spirits, and those are not necessarily permanently resident within the carnal body of the person, but are more closely associated with name and ritualised objects.

In one of the creation stories that form a part of the oral tradition of the Hadza people, mankind descends from a baobab tree, while another has the ancestor of the Hadza being the baboon. This, again, indicates an animist worldview which incorporates the natural world upon which they are reliant. Indeed, the Hadza are so ancient and mutually subsisting within their environment that the Honeyguide bird has evolved alongside humans to lead them to honeybee colonies, scavenging the waste material from such a human raid.

This leads me to my second realisation while watching the film Tawai, named for the Penan word that indicates their relationship to the forest, the assurance that their needs are catered for as a mother cares for her young. In a moment, I became aware that these people are the very ancestors to whom many of us might direct our prayer; the ancient, tribal, animistic, naturally existing humans who sit still at the cradle of civilising society.

These endangered indigenous peoples represent the worldview and way of living that occupied 95% of human existence, with as little as just 5% of our time being formed by civilisations since the dawn of agriculture. Where our most distant, ancient ancestors organised into cooperative, tribal groups in the Late Stone Age, some 50,000 years ago, the beginnings of human society occurred. Suddenly, it is shocking and alarming to realise that those very same ancestors are there still, in parts of Tanzania (Hadza), Congo (Mbendjele), and Borneo (Penan). The most hoary ancestors to whom we might think when we address our attention and awareness toward that romantic hunter gatherer society, existing in a spirit haunted world, alive with all interconnected oneness of symbiotic existence, are alive today, and we are destroying them. By we, of course, I mean our collective modern world which includes the mindless acquisition of goods, almost entirely unnecessarily, and all reliant upon manufacturing methods that are unethical and stripping the planet of necessary resources. Coupled with such processes are the political connivances that aspire to the accoutrements of power, the protection and hoarding thereof – all to the detriment of the indigenous populations of hunter gatherer peoples, who possess little material wealth, living in harmony with the environment which nurtures and sustains them.

I wonder, then, if doing more to help build awareness of the issues affecting indigenous peoples is not ancestral work most worth doing. If building a practice of ancestor work, of venerating the dead, does not include those ancestors who are represented in the living communities of indigenous people across the remote parts of the world then we are in grave danger of the most violent hypocrisy. I, for one, am not sure I can live in the knowledge that I upheld a romantic notion of ancestors and their worldview, practice and magical existence, while neglecting to do anything to help, and limiting the harm I cause to this very people today.

Can we include the Penan, Hadza, Mbendjele and other indigenous, tribal, hunter gatherers in our prayers? Even better, can we commit to reducing the harmful use of plastics and unethical commercialism that encourages gross abuses of the rights of the peoples and land? It is a big ask in our current worldview – so embedded are the structures that coalesce like an abusive codependent relationship, occupying every nook of our existence. But if we don’t work at it, consider our priorities and what we are prepared to change in order to work with living ancestors, they will be consigned to the spirit world forever, and may therefore be undesirous of working with us at all.

Here are nine ways to support the rights of indigenous peoples., from The Guardian. It’s a start. Also, watch Tawai and follow the work of Bruce Parry. Stay informed and be proactive.