There has been much made in recent decades about the pagan origins of Christmas customs. It is important to note that this idea is not, strictly speaking, an accurate portrayal and is symptomatic of unhelpful reductionism. It does form, however, a broader sentiment in modern Neo paganismto reject anything that smacks of Christianity, and this often throws the baby out with the bathwater. Life, belief, perspective, traditions, customs and accompanying lore form a part of an unfolding spectrum and history is no different. Where something is positioned in its beginning does, indeed, inform its original intent and meaning, but does not always reflect its greater, overall purpose, utility, or continuation. Traditions are frequently like this, as has previously been discussed on this blog, and in other articles such as at Llewellyn. Traditions are complex and intrinsically linked to people for their survival — thy are a living expression of us all who come into contact with any given heritage. This means there is inevitable change, adaptation, incorporation of new ideas or perspective, and the abandonment of those parts that have become moribund or detrimental.

In terms of seasonal lore and customs, midwinter is perhaps the most prolific time of the year for traditions and observance, some of which have very ancient roots. Arguably, a host of modern traditions, as they have arrived in the twenty-first century, find themselves sharing a similar or identical root stock. In the broadest sense, midwinter festivals have been with humans occupying the northern parts of the globe as long as we have lived in such difficult climates that provide hard winters. This natural factor informs the most part of north European folk customs from which many modern interpretations emerge. In its simplest form, the depth of winter involves long nights and periods of severe darkness, biting cold temperatures, a veritable dearth of sustenance and a general lack of signs of life. Death, therefore, is the predominant theme for the myths and lore that are born at midwinter and reflects the seasonal activities that are inspired to encourage sunlight, greenery, food and merriment — a reversion of the darkness, barren landscape, seasonal famine, and cruel demeanour otherwise characteristic of a basic existence in the cold north.

In essence, the midwinter solstice features in many cultures, ancient and contemporary, as a moment whereby the sun moves from apparently diminishing at the longest night to being reborn as the days begin to lengthen. Similarly, earliest cultures preserved the sacredness of fire — humankind’s greatest single discovery — and the necessary heat and light that it provides in the bleak, sombre stygian season. Perhaps for this reason, the light has a place within many European cultures — especially those in the more northerly regions.

Lussinatta — the Long Night

In Scandinavia, Lussi is a figure of particular relevance who is celebrated on the 13th December. Due to the use of the Julian calendar in medieval Europe, the Feast of St Lucy coincided with the winter solstice, which occurred on the 13th December. Since the adjustments of the Gregorian calendar, the solar event has since diverged from the calendrical timing, but the date has remained. The Christian feast day commemorates Lucia of Syracuse (St. Lucy), a fourth century martyr who brought aid to Christians during Diocletianic Persecutions. As Christians hid in the Roman catacombs, Lucia wore a wreath of candles upon her head in order to render her hands free to carry her aid to the persecuted Christians.

The association of Saint Lucy with the light, together with the candlelit head, coincided perfectly with midwinter festivals of light and its renewal, providing sustenance and succour in the dark, cold part of the year. In Scandinavia, Christian tradition persists and Saint Lucy is represented by young girls, usually adorned in baptismal white which is seasonally appropriate as representative of another feminine face of winter.

As an earlier, more syncretised pagan figure, Lussi similarly is symbolised by white, the colour of the Snow Queen, and the dark mother — a guise of the Pale-Faced Goddess of poet and author Robert Graves (The White Goddess). Lussinatta, Lussi Night, also takes place on the old solstice date of the 13th December. Lussi is, however, a rather darker figure and representation, as we shall see. Indeed, at Lussinatta, it is ill-advised to venture out at night, especially young children who had been mischievous in the year, as Lussibrud — Lussi Bride — rides upon the wind with her train of Lussiferda, a cipher of the Wild Hunt.

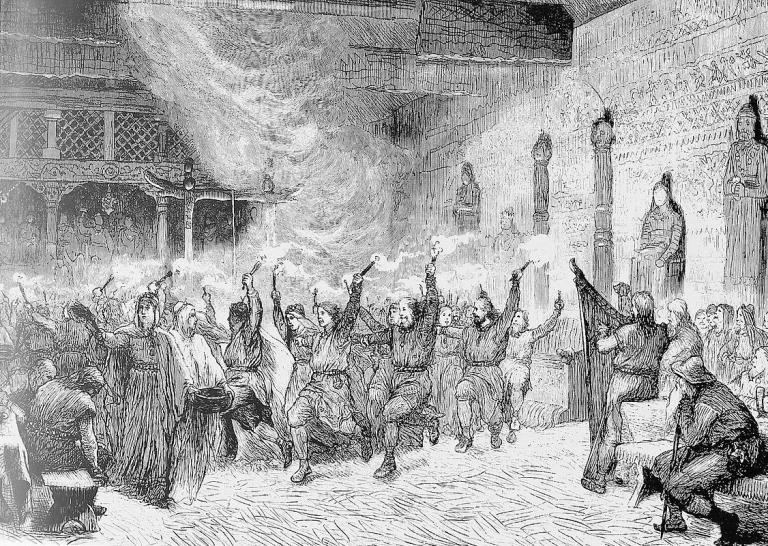

Oskoreia, Lussiferda, Perchta and the Wild Hunt

While much has been said of Odin and his night-riding train being a potential source for the sleigh-riding Santa Claus — the Scandinavian flying goat prefiguring his airborne reindeer — north European folklore more often has a feminine spirit at this time, presiding over the dark heart of midwinter. Perhaps, as the role of woman is traditionally one that is both womb and tomb, she who births into the world and cuts the cord, it is to this ancestral mask of death that the depth of the cold darkness is dedicated. Therefore, it is Lussi, Perchta, and the Oskoreia — led by Gudrun — that occupy the period of midwinter proper, as harbingers of Fate envisaged in myth and lore through the craft of spinning and weaving.

The now beneficent, jolly face of Saint Nick, even as an echo of Odin or a localised pagan spirit, is certainly not the fearsome face of midwinter; it is not his warm, red, rotund revelry that haunts the night and motivates humankind in the cruel time of year. It is the Snow Queen, the Pale-Faced Goddess who wields the distaff in the northern sky (Orion’s belt), stalking the weak, infirm, those who don’t honour the harshest of seasons — those who neglect their spinning, firewood gathering, meat roasting and preserving, and who are out late at night in the cold winter air. The word distaff means ‘flax stick’, and is the oldest and most basic means of spinning thread, twine, or wool. Perhaps the root word etymologically finds its companion in the Nordic Disr, the Norns or Fates as ancestral spirits in Norse mythology. Indeed, the etymology is often obscure, but just maybe the shared root suggests that these weavers of fate are related to the flax (dis-). The Disr were honoured at the Disablót, a winter sacrifice meant to propitiate the ancestral spirits of fate, the mothers of womb and tomb. Marking either the onset of winter in early November (All Hallows), or its conclusion in February (Candlemas), remnants persists today in the Disting, an annual market held at Upsala, Sweden, since pre-historic times, and takes place on the first Tuesday of February.

Given the association with the Pale-Faced mother Goddess, it is unsurprising that the Anglo-Saxon equivalent, which takes place on Christmas Eve, is Mōdraniht, Mother’s Night according to the Venerable Bede. Widely believed to be related to the Disablót, it is thought that the Mother’s Night commemorates Dame Fate and the Disr as the motherly source of both life and death, appropriately consuming the dying sun, and rebirthing it in the depth of midwinter. Of course, this sounds remarkably similar to the story of the birth of Christ and we must resist the temptation to draw comparison, or reflect that Christianity subverted pagan tradition. The advance of two thousand years of history and culture is the true culprit in the development of our midwinter festive season and traditions, and similarities between cultural depiction and representation is inevitable, adopting some, appropriating others, producing new ones and evolving the whole.

The Wild Hunt motif carries throughout north European cultures, and Lussi is no exception. The Oskoreia are a variety of the Hunt, deriving from the Old Norse word for “terror”, and are sometimes called Åsgårdsrei — Asgard Ride — and jolorei, — Yule Host.[1] Typically, the leader of this midwinter version of the hunt is feminine, perhaps due to the womb and tomb nature of the solstitial event, presiding over the death and rebirth of the sun/light — as in the case of Lussibrud, the “Light Bride”. The usual motif remains reasonably consistent, and the most at peril are the elderly and infirm — for whom death is a constant companion — and, of course, children. Indeed, naughty children are warned into good behaviour lest the Oskorei are inclined to whisk them up, or Lussibrud might descend the chimney to steal them away.

Of course, the most frequently recognised witch queen, leader of the hunt, and mask of the Pale-Faced Goddess in her dark aspect is Perchta. Like Lussi, Perchta is associated with, and sometimes appears, robed in snow white. Indeed, her name may indicate ‘bright-one’, suggesting the brilliance of white snow in winter, and the light that is dying and reborn. Typically, Perchta has two forms and is not always the virginal white, beautiful maid but also the terrible hag, old and crooked. This dual appearance, therefore, is perhaps indicative of her nature as the weaving spinning mother of fate, the bringer of life, and the angel of death. Indeed, so important is this aspect of Perchta that she is found overseeing spinning activities over the festive period, particularly the Twelve Days of Christmas, as though emphasising her function, role and connection with the Disr and Norns. In this capacity, the folklore collector Jacob Grimm reckoned Perchta as a guise of the goddess Holda. Holda, like Perchta, presides over winter activity and is commonly associated with spinning and weaving, riding a distaff and associated with witchcraft in Catholic German folklore.

In the alpine region of Austria, the Perchten (pluralised Perchta) denotes the entourage, or spirits of their iteration of the Wild Hunt. The Perchten traditionally take two forms, again reflecting the twin faces of Perchta — one beautiful and one ugly. In the 16th century, these two forms have appropriate roles with the beautiful aspect bringing good-fortune and blessings to households, while the ugly form was used to drive out bad or unwanted spirits and misfortune. The appearance of the Perchten in their ugly guise has become a popular image shared amongst Neopagans as representative of pre-Christian custom, often mistakenly identified with the similarly popular Krampus. Austrian festive traditions involving the Perchten have been adopted by Neopagans as representative of pre-Christian traditions, but this again is a rather more complex reality.

As the winter season unfolds before us, and folklore and custom are to the forefront of our minds, it is important to remember that, like the Wild Hunt, our modern traditions have gathered up the spirits of those that have come before. Some have been assimilated with ease, finding common bedfellows, whilst others have more problematic origins (like the Dutch Zwart Piet). In this process it is important to remember that human history is not a black and white process of Christian and non-Christian beliefs, but a spectrum of perspectives that meet in a melting pot of culture. In this cultural soup, we can identify flavours our particular palette prefer and some that we have learned to find less favourable. What is essential, however, is to understand the spirit that informs the customs and traditions of the season and respect the different forms that may take, depending upon each of our perspectives.

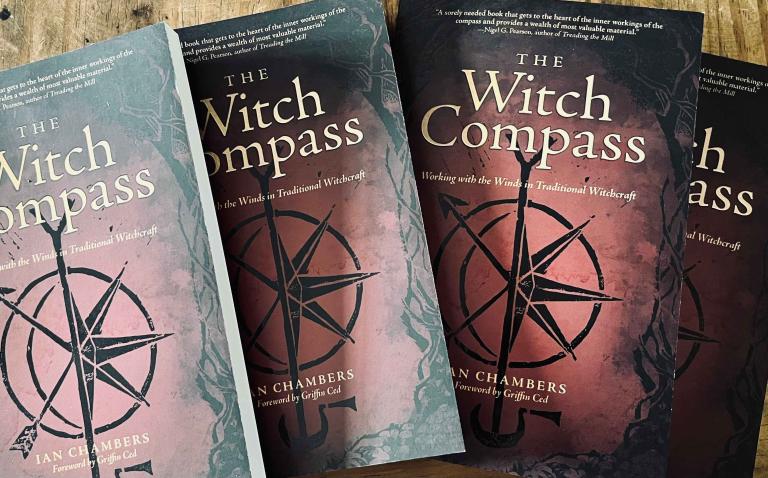

[1] Raedisch, Linda, The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2014, p. 75.The Witch Compass: Working with the Winds in Traditional Witchcraft

The Witch Compass is Ian Chambers’ first book, published in 2022 with Llewellyn, and is available through all good booksellers. Signed copies of The Witch Compass are available from the author’s website: surrey cunning.co.uk

Explore the compass of the eight winds, a magical circle at the heart of Traditional Witchcraft. More than a tool for protection or raising power, this framework provides the ritual means to traverse the worlds and a mythic landscape that can be accessed at any point in time and space. Traditional Witch Ian Chambers teaches how the Witch Compass represents an entire worldview, a cosmological map, and a method for magic and revelation. He helps you develop your own compass and use it for divination, spirit work, and practical sorcery. This book shows you the world through the lens of your Witch Compass and reveals the many realms and spirits available to you.

“With this invaluable book, the aspirant unto traditional Craft and the seasoned practitioner alike are carefully guided through the workings of the compass as the map, via which the Crafter may traverse magical realities, encounter spiritual presences, and commune with ultimate Truth.” – Gemma Gary, author of Traditional Witchcraft, A Cornish Book of Ways.

“A scholarly, inspiring, and eminently informative work. I give it my highest recommendation.” – Lon Milo DuQuette, author of The Magic of Aleister Crowley.

“I found this a most fascinating and informative book, describing as it does the rationale behind the actual working of the compass, with plenty of practical demonstrations and exercises to enable the reader to experience the compass for themselves…This is a sorely needed book that gets to the heart of the inner workings of the compass and provides a wealth of most valuable material for both the beginner and more experienced practitioner alike. I congratulate Ian on producing an approachable and understandable book which will add greatly to the sum of available knowledge on a sometimes obscure and difficult subject.”―Nigel G. Pearson, author of Treading the Mill.