A long time ago, in my early teens, I had a secret and insatiable thirst for knowledge of the magical arts. Growing up in Aleister Crowley’s hometown, the Beast’s shadow loomed over the cultural landscape of the town. However, I instead used the cover of studying magic in Shakespeare’s play The Tempest to learn about renaissance sorcery. Of course, Elizabethan astrologer and polymath John Dee provided an evident influence for the play’s central character of Prospero, who banishes witches, works with fairy folk and summons great storms. Prospero afforded the opportunity to openly gather information about the practical occult experiments of the early modern period, supported by enthusiastic literature teachers who were keen to encourage a burgeoning interest in the arts.

Little did I know that those Elizabethan magics, so distantly remote and apparently out of reach, would one day be available to study in greater depth through the source material. I could never know that I was destined to turn the pages of John Dee’s own manuscripts in the British Library many years later. It is, then, a sheer delight to study recently published literature from the Elizabethan period, such as the Book of Oberon which explores the remarkable magic and context that generated such works, and presenting the text itself for study.

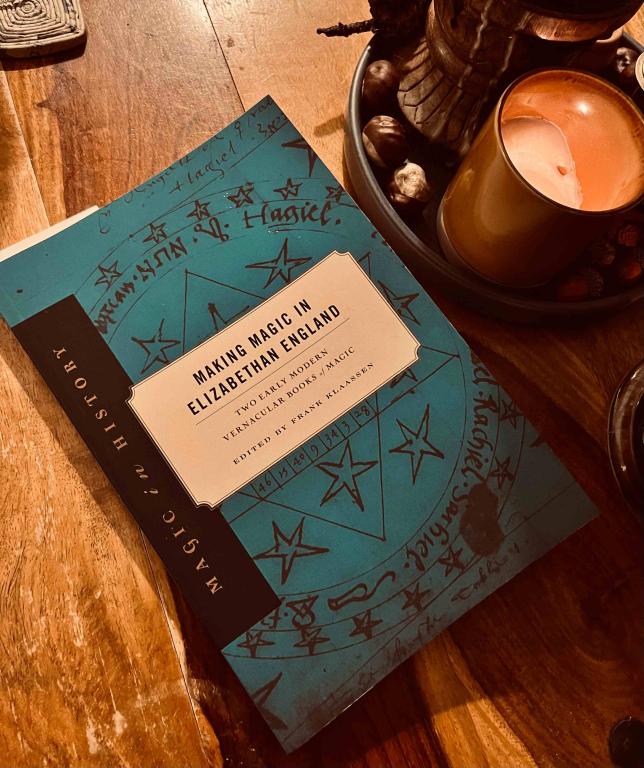

One such sourcebook for Elizabethan magic, Making Magic in Elizabethan England: Two Early Modern Vernacular Books of Magic is a gem for the historian and student of renaissance esotericism. Editor Frank Klaassen provides much needed cultural background for the two manuscripts discussed, setting the scene for the magic that developed out of medieval necromancy and sorcery to reveal some of the evolution through the seismic phase of the Reformation and into the modern English occultism.

A part of the Magic in History series from Pennsylvania State University Press, the book provides truly fascinating insight. Apart form the practical textual evidence, the expert analysis and introduction from Klaassen offers the much needed locating of the manuscripts in time and place. Indeed, the lay student of magic might overlook the necessary conditions in which the texts were formed and it is fundamental to understand the circumstances that produced these works; only then may we start to appreciate the development of magic in the period, how it transitioned from the medieval and matured before arriving in a post modern world. The Magic in History series is a collection of sourcebooks providing translations and expounding key ideas present in the development of magic as a cultural phenomena.

The basis of Making Magic in Elizabethan England are two manuscripts from the period, the Antiphoner Notebook and the Boxgrove Manual. The former is the first presented and is uniquely positioned in the time period in its composition — in terms of both physical matter and content. Being composed of material salvaged after the abolition of the monasteries in England, the manuscript is a curious artefact made from the wide margins of liturgical books that were cut from the discarded pages and folded to form a new, portable notebook. The contents include a very basic comprehension of Latin, or else its inclusion as a magical language that would impress the clients of a cunning man, and move from careful handwriting to a more casual style. Traversing ritual magic to common charms and experiments, the manuscript is evidently the working book of a practical charmer and magician — a cunning man. The move from Latin — and Klaassen observes that the author evidently copied Latin, but couldn’t compose original works in the language — and use of charms demonstrate a link to medieval sorcery, but the translation of much into vernacular English demonstrates the move away from the popish magics of the middle ages. What is most apparent, as Klaassen notes, is that the Notebook is clearly the work of a moderately or poorly educated, practicing cunning man and not the learned, clerical manuscripts commonly associated with high magic of the age.

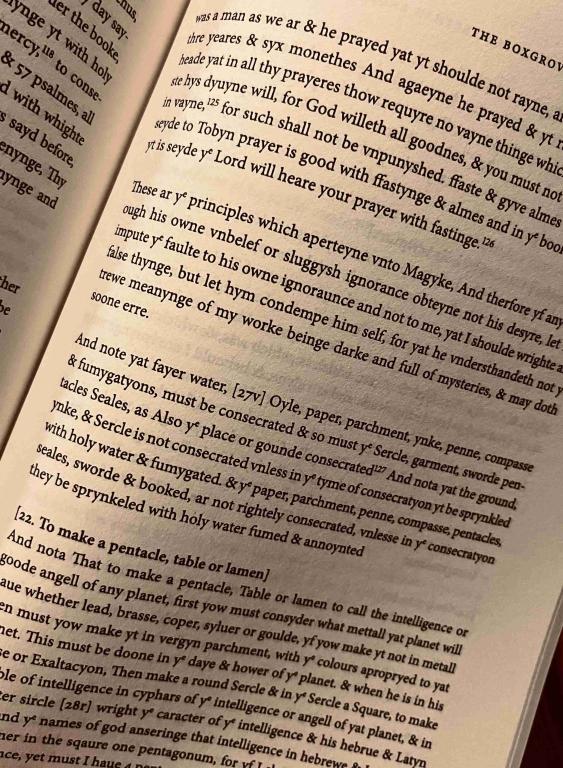

The Boxgrove Manual, by contrast, epitomises the learned class of Elizabethan magic, owing much to the medieval processes of occultism yet possessed of the latest technology and thinking upon the subject. Indeed, Agrippa is evidentially an influence upon the author of the original manuscript, of which the Boxgrove Manual is a copy. The cleric who copied the manuscript was not as careful as they might have been, and the original author of the text is now lost to history. The dating of the manuscript, and the references to particular editions of Agrippa, provide a date point for the original.

These two works in the vernacular represent intriguing source material for the intersection between the superstitious, Catholic magics of medieval Europe and the renaissance and early modern esotericism that was emerging and informs today’s occultism. In its simplest form, the transition from Latin — a magical, liturgical and legal language that was lost to the ordinary person — to the common tongue marked a significant and obvious benchmark in the development of English magic. The translation of religious rite and prayer into the vernacular placed religion in the hands of the people once more, returning the spirits to the homes of the everyday folk. However, the power of charms, whether spoken in Latin or English, retained their especial place as words of magic.

As a sourcebook, Making Magic in Elizabethan England provides a truly fascinating insight into the working of magic at the time. It is a genuine window into the minds of practicing magicians, cunning folk and regular people. In addition, it speaks to the changing nature of magic, its focus, techniques, methodology, and cultural context and influences. My teenage mind would have devoured this book, and used its contents!

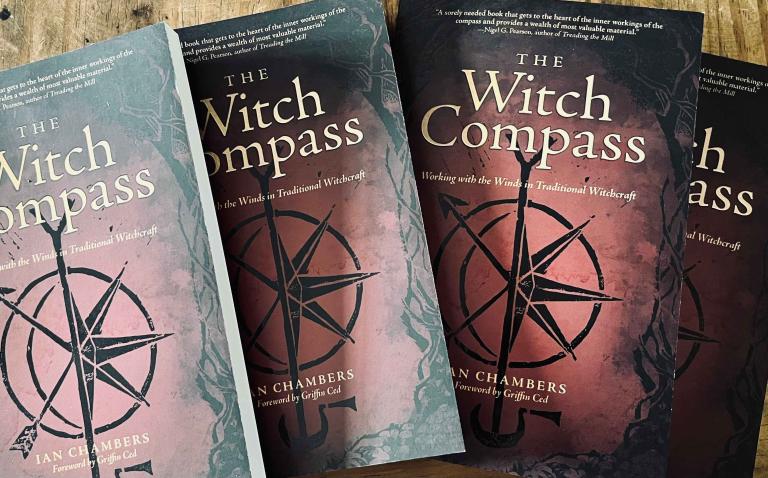

The Witch Compass: Working with the Winds in Traditional Witchcraft

The Witch Compass is Ian Chambers’ first book, published in 2022 with Llewellyn, and is available through all good booksellers. Signed copies of The Witch Compass are available from the author’s website: surrey cunning.co.uk

Explore the compass of the eight winds, a magical circle at the heart of Traditional Witchcraft. More than a tool for protection or raising power, this framework provides the ritual means to traverse the worlds and a mythic landscape that can be accessed at any point in time and space. Traditional Witch Ian Chambers teaches how the Witch Compass represents an entire worldview, a cosmological map, and a method for magic and revelation. He helps you develop your own compass and use it for divination, spirit work, and practical sorcery. This book shows you the world through the lens of your Witch Compass and reveals the many realms and spirits available to you.

“With this invaluable book, the aspirant unto traditional Craft and the seasoned practitioner alike are carefully guided through the workings of the compass as the map, via which the Crafter may traverse magical realities, encounter spiritual presences, and commune with ultimate Truth.” – Gemma Gary, author of Traditional Witchcraft, A Cornish Book of Ways.

“A scholarly, inspiring, and eminently informative work. I give it my highest recommendation.” – Lon Milo DuQuette, author of The Magic of Aleister Crowley.

“I found this a most fascinating and informative book, describing as it does the rationale behind the actual working of the compass, with plenty of practical demonstrations and exercises to enable the reader to experience the compass for themselves…This is a sorely needed book that gets to the heart of the inner workings of the compass and provides a wealth of most valuable material for both the beginner and more experienced practitioner alike. I congratulate Ian on producing an approachable and understandable book which will add greatly to the sum of available knowledge on a sometimes obscure and difficult subject.”―Nigel G. Pearson, author of Treading the Mill.