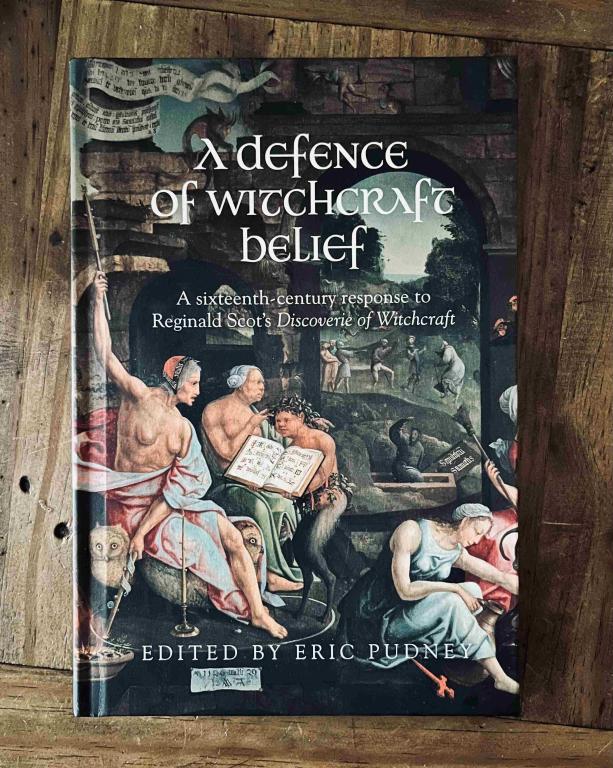

A Defence of Witchcraft Belief: A Sixteenth-century Response to Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft, Edited by Eric Pudney, Manchester University Press 2023

In 1584, the would-be know-all, university dropout and so-called authority on the subject of early modern witchcraft, Reginald Scot published his now famous book The Discoverie of Witchcraft. This tome was dedicated to the intellectual, reasoned pursuit of the Protestant view of early modern witchcraft as naught but a relic of superstition and was contemporaneous with other less known treatises published around the time of religious reevaluation of the Reformation period. So assured was Scot in his lengthy opus that he adopted an often cavalier approach to interpreting scripture, law and belief during a turbulent time when schisms and reformations within Christianity had produced several seismic shifts in religious belief and a number of doctrinally different groups. In his own lifetime, being born around the time of the separation of England from the Roman Catholic Church, the official religion had changed three times. The severe differences between Roman Catholic and Protestant doctrinal theory and belief — and thus ritual expression and practice — was such that most regarded them as utterly opposing religious worldviews. Therefore, being legally pressured into changing religion on the accession of a new monarch and government, under threat of persecution that was often violent, could be safely regarded as rather traumatic.

Scot, a pug nosed minor gentleman — he boldly ascribed himself the aspirational title esquire on the title-page of his Discoverie[1] — author and occasional Member of Parliament sought to disabuse the common belief in witchcraft through exposing deceits, trickery and misplaced interpretation of not just the Bible but also popular theologians, from St Augustine to the reformer John Calvin. Scot aligns himself firmly in the camp of Reformed Protestantism, while maintaining an intellectually proto-rationalist approach to interpreting religious belief as the basis for apprehending a Christian worldview. In this, God being the creator and sustainer of all does not allow for the existence of witches or demons who might have their own power independent of God. This constitutes the basic of Scot’s position, which also found superstitious belief irrational, a position indicative of the intellectual stance that was developing among the urbane and effete that were emerging amongst the authorities and scholarly quarters around the city of London. Of course, the culprit of such sustained superstitious and irreligious belief was the Old Religion, Roman Catholicism, and it had become à la mode for aspiring gentry to apportion such thinking to papist idolatry and magic. Of course, such an expression was to court favour in the circles around Elizabeth and her entourage, who had restored a traditionalist brand of Protestantism that respected Reformed doctrine, while observing certain elements of medieval Catholicism, suggested in liturgy and ritual with a prudent nod to the parent religion — “Catholic structure and Protestant theology”.

Scot’s book, while extensively presenting its detailed arguments and reasons against the belief in witchcraft in the early modern period, nevertheless became a resource that included many examples and recipes used by witches, cunning folk and the superstitious populace. In that, it rapidly became a sourcebook and grimoire in its own right, providing useful instructions and information regardless of the overarching stance that its thesis takes on the efficacy of such acts. It is a thing of pure an delicious irony that Scot’s Discoverie remains a significant source for early modern witchcraft belief and practice, despite the intention of Scot being to disabuse us of the notion of such things.

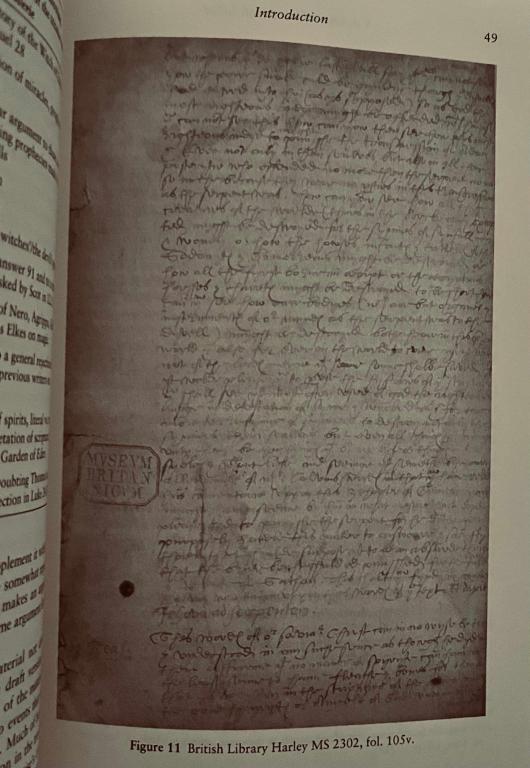

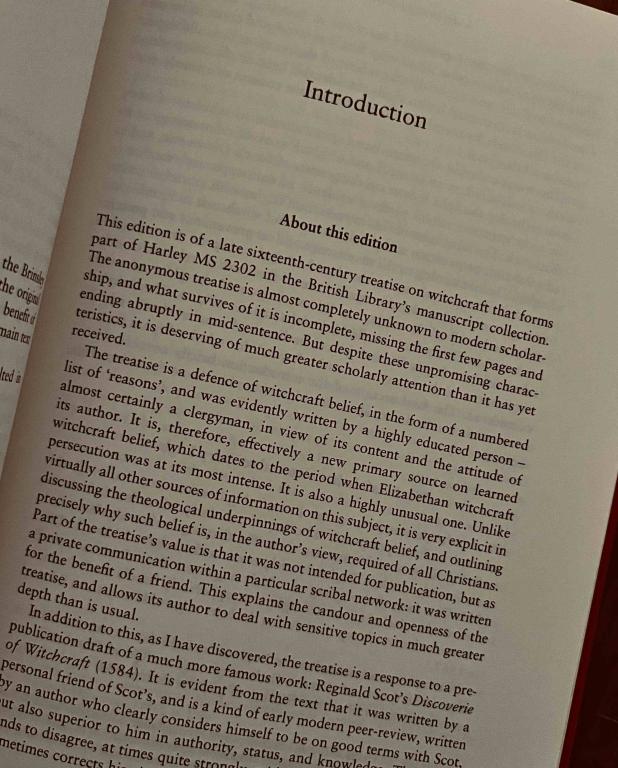

When Scot had penned his first drafts of the manuscript, he sent copies out to friends and colleagues to harvest early critique and, presumably, endorsement. This brings us to the book under review, A Defence of Witchcraft Belief: A Sixteenth-century Response to Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft, edited for Manchester University Press by Eric Pudney. This book is remarkable in that it preserves a treatise by one of these associates of Scot to whom he had evidently proffered his early manuscript of Discoverie. The unknown author of the treatise which forms the subject matter of A Defence of Witchcraft Belief, which exists only in a few pages preserved in the British Library as part of Hartley MS 2302, is thought to have been a personal friend of Scot, and the Introduction by Pudney speculates over the candidates for whom this could potentially be. The Introduction to A Defence of Witchcraft Belief is worth the price of entry itself, being a superb and thorough discussion of the key elements for consideration when approaching this significant work. It is worth noting that the manuscript of the treatise reproduced and discussed in Defence was written for Scot alone and therefore was never intended by its author for public reading or scholarly study — its familiarity and candour are reflective of that pertinent consideration. The Introduction, then, constitutes the bulk of the book and takes us on a very good and solid sojourn through witchcraft in late sixteenth-century England, the provenance and date of the manuscript, its authorship, the significance of the treatise and its relationship to Scot’s Discoverie.

Positioning the treatise in its own turbulent and difficult time, Pudney does an expert job of locating us within the spirit and mind of those early modern thinkers who were qualified and educated in such things as law and theology. In speculating over the authorship of the treatise, it is evident that the anonymous author had knowledge and experience of witch trials, so could have schooling and experience of legal and religious studies or concerns. Indeed, the main argument of the author of the treatise comes from the position of Scot’s inadequate and rather simplistic interpretations of scripture ad doctrine. Indeed, it is in this that the author makes the strongest case against Scot and, therefore, in favour of a belief in witchcraft on the grounds of theological exposition and understanding. The author of the treatise holds a peculiarly English view of witchcraft of the period, dismissing certain elements from the Malleus Maleficarum and Catholic demonology, as well as pacts with demons — although this doubt is qualified by stating that it is possible in theory at least. These arguments demonstrate the differences that later historians have observed between the trial record of witchcraft in England and that of continental and even Scottish samples. It also demonstrates that the author of the treatise appears to have a better familiarity and more acuity when thinking upon the subject than does Scot.

Overall, Defence is a scholarly and serious look at a rare and previously unaddressed aspect of early modern belief in witchcraft. The anonymous author of the treatise presents a precious glimpse into the thoughts of contemporaries of Scot, providing a critique that was not just current but directly addressed to the author of Discoverie. That Scot’s friend so widely criticised his reasoning and arguments is indicative of an educated mind and a range of views around the subject at the time. It is not clear that Scot adopted much of the counter-arguments of the anonymous author, nor that his imploring of Scot to reconsider some of his poorly argued points or interpretations had much affect upon the published work. Indeed, in parts, the treatise is a scathing attack on the logic and reasons of Scot, always with a view to the author’s experiences of witchcraft — which appear to be more significant that Scot’s — together with his knowledge of law and theology. As an alternate view of the reasoning of Elizabethan England, it is important that this work is taken into account when regarding any serious study of Scot in particular, and early modern witchcraft in general. Indeed, it transpires that Discoverie is not singularly representative of the pervading intellectual belief of the time and, according to the treatise in Defence, not particularly the most studiously argued. Pudney does an excellent job of exposing where Scot likely expanded areas of Discoverie, comparing manuscripts and editions that reveal that the earliest drafts may have been especially and purposefully sparse in detail and rather more like a list of arguments.

In all, A Defence of Witchcraft Belief is a wonderful book, thoroughly covering a lot of ground that is pertinent to the belief in witchcraft in the late sixteenth century. The time period, theologically and politically, was a very nuanced and difficult area of study, sufficient that professors have dedicated entire lives to the study thereof. Therefore, the elucidation provided by Pudney is equal in quality to the import of the treatise presented. There is no issue, then, recommending this work to any serious student of witchcraft in the early modern period — indeed, it may arguably become required reading. Having read the astute and considered arguments, from what remains of the manuscript treatise, I have no qualms in expressing the description of Scot with which this review was opened. There is certainly a case for the fact that Scot’s argument against witchcraft belief is not perhaps as strong — using his own parameters of the day — as his conviction in the pursuit!

[1] In 1580, the Somerset Herald Robert Glover drew up a list of those entitled to the use of the term esquire, which included those so styled in the execution of the King’s commission, such as Sheriff or Justice of the Peace, and who cease to hold the title when no longer in office. It has been assumed, then, that Scot was perhaps a JP when publishing Discoverie to afford himself this title.His grandfather, Sir John Scott, was a Knight Bachelor who had served in Henry VIII’s campaigns in France. His uncle, Sir Reginald Scott, Sheriff of Kent, inherited Sir John’s estate after the death of the eldest male heir, William, and was himself knighted in 1542 as Captain of Calais and Sandgate (W A Shaw. The Knights of England, Vol. II, Sherratt and Hughes, 1906, p. 52).

Scot’s father was thus untitled, but seems to have also styled himself esquire — although this may have been legitimate as he was the son of a Knight, who himself was the son of a Knight (Sir William Scott).

Knight Bachelor is the most ancient, common and non-Chivalric order of knighthood in England and is non-hereditary. In the modern British Honours system, this is the most frequent Knighthood bestowed annually for good works.

The Witch Compass: Working with the Winds in Traditional Witchcraft

The Witch Compass is Ian Chambers’ first book, published in 2022 with Llewellyn, and is available through all good booksellers. Signed copies of The Witch Compass are available from the author’s website: surrey cunning.co.uk

Explore the compass of the eight winds, a magical circle at the heart of Traditional Witchcraft. More than a tool for protection or raising power, this framework provides the ritual means to traverse the worlds and a mythic landscape that can be accessed at any point in time and space. Traditional Witch Ian Chambers teaches how the Witch Compass represents an entire worldview, a cosmological map, and a method for magic and revelation. He helps you develop your own compass and use it for divination, spirit work, and practical sorcery. This book shows you the world through the lens of your Witch Compass and reveals the many realms and spirits available to you.

“With this invaluable book, the aspirant unto traditional Craft and the seasoned practitioner alike are carefully guided through the workings of the compass as the map, via which the Crafter may traverse magical realities, encounter spiritual presences, and commune with ultimate Truth.” – Gemma Gary, author of Traditional Witchcraft, A Cornish Book of Ways.

“A scholarly, inspiring, and eminently informative work. I give it my highest recommendation.” – Lon Milo DuQuette, author of The Magic of Aleister Crowley.

“I found this a most fascinating and informative book, describing as it does the rationale behind the actual working of the compass, with plenty of practical demonstrations and exercises to enable the reader to experience the compass for themselves…This is a sorely needed book that gets to the heart of the inner workings of the compass and provides a wealth of most valuable material for both the beginner and more experienced practitioner alike. I congratulate Ian on producing an approachable and understandable book which will add greatly to the sum of available knowledge on a sometimes obscure and difficult subject.”―Nigel G. Pearson, author of Treading the Mill.