The Black Fast

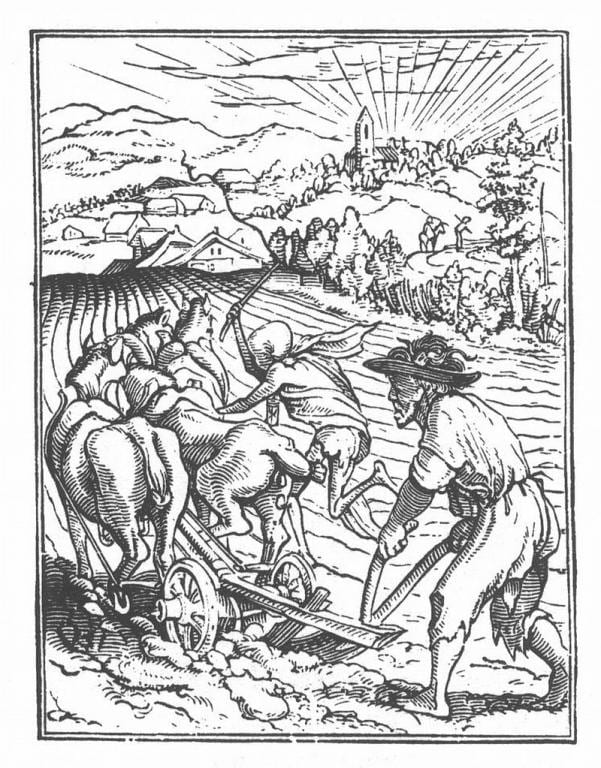

In the Year of Our Lord, 1537, the potato arrived in Europe, the Dissolution of the Monasteries (which commenced the year prior) was under way in England and the ten year old John Dee (derived from Welsh du, meaning ‘black) attended Chelmsford Chantry School. In the Summer of that same year, Mabel Brigge, a widow and serial faster, house servant to the Lokkar family in the East Riding of Yorkshire, was hired to perform the Black Fast. Around Lammas 1537, on the Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Brigge performed the Black Fast on behalf of Isabel Buck, who was unable to carry out the rite herself due to having recently lost an infant. The purpose of the fast, we are told, was in order to recover some lost moneys of Buck. Brigge was paid with a ‘peck’ (equivalent to 2 dry gallons) of wheat and half a yard of linen and informed her employer, John Lokkar, that it was a charitable fast. (Alvarez, 2016).

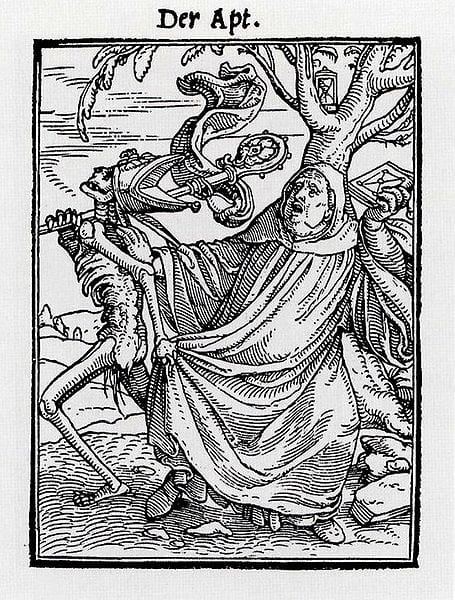

Mabel Brigge was subsequently hanged on 7th April 1538 in the city of York following a trial which found her guilty of the crime of treason. The 32 year old mother of two, it is alleged, had previously performed the Black Fast, also known as the St Trinian’s fast (Alvarez, 2016), in order to kill a man who, indeed, subsequently broke his neck. According to the charges levelled against Brigge, as well as Isabel Buck, this latest fast was actually performed in order to kill the King, Henry VIII, as well as Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, uncle to no less than two of the King’s wives (Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard). That the Black Fast is a feature of extreme Christian devotion, and that the accused had received permission from the Chantry Priest, Sir Thomas Marshall, who confirmed his consent during the trial, nevertheless it was deemed an act of witchcraft employed to bring about the death of the monarch. And the penalty for treason was death by hanging.

The details of the case of Mabel Brigge are as confusing as any from the Witchcraft trials of the early modern period. Indeed, it seems that the allegation arose from Agnes Lokkar, wife of John, who asserted at the trial that Mabel Brigge had undertaken the fast for treasonous purpose. It appears that John Lokkar put Brigge out of his household and into the service of another, where she performed another Black Fast (as she called it). For being thought to have stolen money, she was beaten and thrown out – although she denied these charges too. It transpired that the Lokkar family levelled the accusation that Brigge had fasted as a magical means to bring about the King’s death after receiving payment for such from Isabel Buck. Indeed, Brigge alleged that it was not Buck who had tried to buy her fasting services against the crown, but John Lokkar himself, who offered seven shillings to bring about the death of Henry VIII and the Duke of Norfolk. The same Chantry Priest, Thomas Marshall, who confirmed his assent to the fast “…alleged that Mabel had said to John and Agnes that her fast was for mischief, and that he himself rebuked all three of them for slandering each other.” (Maxwell-Stuart, 2014).

Clearly, the case of the Black Fast and Mabel Brigge is one where three parties cast blame upon each other for nefarious actions. We can know with some degree of certainty that Brigge was apt to perform a fast for various purposes and, it would appear, somebody likely did ask her to perform this to bring about the end of Henry VIII and the Duke of Norfolk. These were tumultuous times after all, and the King is still notorious today for his Protestant Reformation and many wives. So, apart from plotting to kill the King, what are we to surmise from this case of the Black Fast and its use?

Firstly, we must consider that the Black Fast as a term that Mabel Brigge used herself during her trial, also referring to it as the St Trinian’s fast. I have been unable to discern the meaning behind the latter, while the former is a legitimate fast that was undertaken on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday in medieval Europe in certain Christian traditions.

The folklorist Christina Hole remarked upon the Black Fast case in passing, reporting that “…during the fast, the witch concentrated all her will-power upon the victim until he died.” (Hole, 1945, p.16). While that may be the effective use purported in the trial of Brigge, it is a far less common intention of the Black Fast in historical context. The Black Fast was designated, according to the Catholic Encyclopaedia, “…the most rigorous in the history of the church legislation” (Hebermann, et al. 1907-12). Although variations over time are noted, in essence the Black Fast consists of a solitary meal permitted in a day, usually after sunset, which precludes a number of prohibited ingredients. At the most basic level, bread, salt, herbs and water are among the foodstuffs allowed. Among the prohibited items at the one meal, it appears that foods obtained from living animals is most common to avoid, as the Catholic Encyclopaedia illustrates: “meat, eggs, butter, cheese, and milk were interdicted” (Hebermann, et al.). The different exclusions and timings of the Black Fast throughout the Middle Ages became concentrated such that, by the early nineteenth century, “… a crust of bread and some coffee in the morning was introduced” (Herbermann, et al.). During the twentieth century, successive Popes relaxed the Catholic requirement to fast, with Pope Paul VI presiding over the most significant reduction of the rigours of practice, although fasting still plays a part in Catholic and other religious observances.

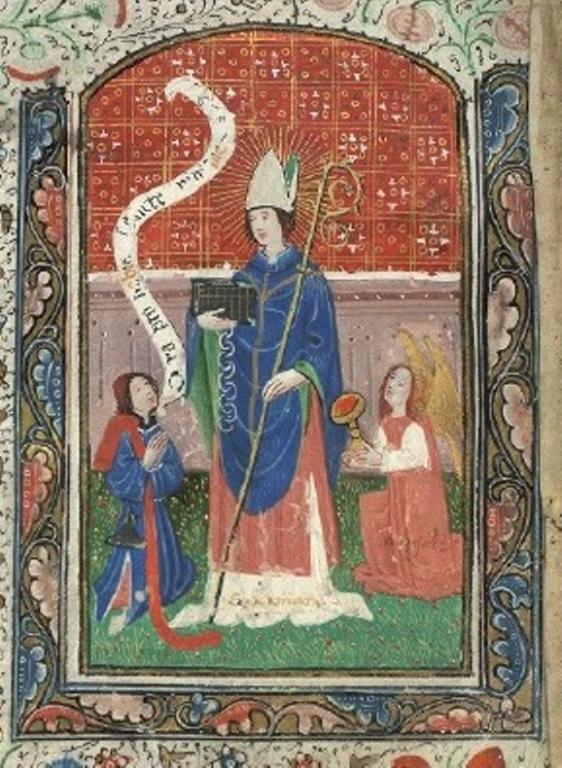

Mabel Brigge referred to her method of witchcraft as Black Fast, but she also called it St Trinian’s Fast. This last name eludes definition somewhat, but it is interesting to investigate, nonetheless. St Trinian is believed to be a corruption or variation of the early Celtic Christian Saint Ninian. Ninian is thought to have lived some time between 360 and 432 CE and is credited with converting the southern Picts, establishing a stone church building at Withorn (OE hwit ærn – White House), Galloway, and here at the ‘Candida Casa’ (White House) trained many Irish Saints.

There is little to no historical relevance of the designation of St Trinian, or Ninian, to the Black Fast used as witchcraft in the case of Mabel Brigge. However, and here we must diverge from historical recorded history and enter speculative theory, there is a precedent for Celtic peoples and law, especially those pertaining to the Irish and Pictish lands of which Ninian belonged, making use of fasting to assert justice and one’s rights – the troscead ritual of fasting. I reiterate that this is my own theory and not necessarily accurate, but it is as good a hypothesis as any.

The purpose of fasting in a religio-spiritual perspective, and in the social context of Brigge, must be understood to place the subject of the trial in its proper place. Of course, the historic time period of Mabel Brigge includes a transitional religious attitude as protestantism began to replace the majesty of Catholicism in England. Whilst Henry VIII is held up as the originator of the separation of England from Papal authority, he was, nonetheless, a deeply Christian man who held to the Catholic ideals in every sense. The conflict between the church and its dissenters, who later formed independent churches in their own right, including the Anglican Church, would play out over the next several centuries and with much bloodshed in Britain and throughout Europe. At the time of Brigge, however, Catholicism would have been the fundamental worldview and informed the respective habitus of the population at large. It is fair to say, then, that the subject of fasting was well established in terms of the common people, as well as those designated as somehow possessed of supernatural power to use the practice for single-minded aims. Often, these individuals would be holy people, especially those who have taken vows to a religious order such as a monastery or nunnery. Outside of the establishment, people would make recourse to those they are familiar with and who had been observed to either be informed in the magical arts, possessed of some power, or else, in the case of Mabel Brigge, able to exercise and brandish their willpower to affect changes in circumstances. The application of the Black Fast in the instance of Brigge included both locating or recovery of lost funds, as well as murder – such a broad spectrum of use is quite surprising today and one would imagine quite unbalanced considering the perceived ‘energy’ one might require to find money, as opposed to kill another. Nevertheless, these were among the remit of Mabel Brigge’s capability and it was regarded perfectly feasible that she could employ her willpower to the same degree with such drastically differing results. Needless to say, life was considerably cheaper in the 16th Century and death a constant companion.

The Troscead

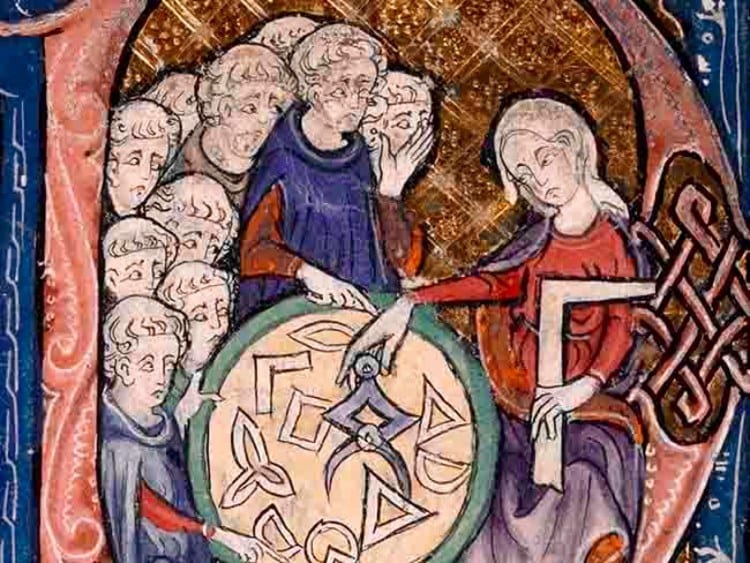

The troscead must first be understood in terms of ancient Brehon Law, an historic body of law held in common amongst the Irish peoples and named for the wandering lawyers, the brehon. These early civic laws constitute a medieval series of statutes which governed how people held themselves responsible and accountable, rather than criminal punishments. The brehon acted as mediators where decisions were required to settle disputes, guided by rules memorised through an oral tradition. As Christianity introduced clerics, a custom of recording these into concrete laws was established and lasted for centuries, although the Norman invasion, 1169 AD, introduced a more formal and feudal legal mechanism through land ownership and property. Brehon Law represents one of the oldest attested surviving legal system in Europe. Daniel Anthony Binchy (1899 – 1989), scholar of Irish linguistics and Early Irish Law, compiled and edited legal texts in a six volume series, including tracts as old as the 8th century. In his journal article, Irish History and Irish Law (1975), Binchy notes the similarity with the Hindu Laws of Manu, including the custom of fasting employed to recover debt or right some wrongdoing. How did it work?

The troscead, “fasting upon one”, was a method under Brehon Law which required the plaintiff to exercise this ancient rite prior to distraining, asserting their claim and seizing the property in recompense if no satisfaction or pledge is received. The troscead required the plaintiff, or representative thereof, to place themselves at the debtor’s door and remain there for a period of time without food. Reporting in Brehon Laws: A Legal Handbook (1894), Laurence Ginnell notes:

“The text says, ‘He who refuses to cede what should be accorded to fasting, the judgement on him… is that he pay double the thing for which he was fasted upon… if the plaintiff has fasted without receiving a pledge, he gets double the debt and double the food.’” (Ginnell, 1894)

It is interesting to note the superstitious application of this method of extracting justice and the possible continuance of fasting as a means of protest, or bringing about ends one desires in accordance with the will. Indeed, the entire process is concerned with the single-minded willpower of the practitioner who undertakes the fast. A muslim friend, while undertaking the Ramadan fast, outlined the importance of observing the fast; that is, attending to the process rather than just mindlessly fulfilling an obligation. Indeed, my associate went into detail to express his understanding that the fast was meant to be a singular devotional act of concerted focus, and included not merely abstinence from tangible things but in all areas, such as anger or pride. This provides a tantalising clue as the process and purpose of Mabel Brigge’s Black Fast.

Any research into the ancient practice of fasting to bring about justice, or else bend circumstance to our will (a magical act in its own right), will include comparison between the Brehon troscead and the Indian non-violent sit-in protest, dharna, which includes fasting at the door of an offender – a direct correlation with the Irish counterpart. In particular, this practice has been used to gain recompense for a debt, much like the troscead, or Brigge’s fasting for Isabel Buck. In addition, like Brigge, those undertaking dharna are often required to seek permission for the fast. Dharna and fasting has more recently been used as a form of peaceful protest, including by Mohandas Ghandi (1869 – 1948) during the contest for India’s independence, as well as by Irish Republicans in the 20th century (Bobby Sands is remembered as the first of ten Irish republican prisoners of the British Government who died during the 1981 Hunger Strike).

Whilst fasting can be seen as an historic method of bringing attention to, and recompense for, an injustice, it is also widely used to bend events to the practitioner’s favour or will. Rather surprisingly, Wikipedia provides the following, and most fortuitous definition to end upon on its page for dharna:

Dharna generally refers to fixing one’s mind on an object. It refers to whole-heartedly pledging toward an outcome or to inculcating a directed attitude. Dharna is consciously and diligently holding a point of view with the intent of achieving a goal. (Wikipedia, 2020)

Bibliography

Alvarez, Alyson (2016). “Mabel Brigge”. A biographical encyclopedia of early modern Englishwomen : exemplary lives and memorable acts, 1500-1650. Taylor & Francis.

Binchy, D. A., “Irish History and Irish Law: I”, Studia Hibernica 15 (1975): 7-36.

Ginnell, L., The Brehon Laws: A Legal Handbook, 1894

Herbermann, Charles G., Pace, Edward A., Pallen, Thomas J. Shahan, Wynne, John (1907-12). The Catholic Encyclopaedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline and History of the Catholic Church. Robert Appleton Co.

Hole, Christina (1945). Witchcraft in England, B. T. Batsford Ltd.

Maxwell-Stuart, P.G. (2014). The British Witch: The Biography. Amberley Publishing Ltd.