The following is from part of what I presented at the recent conference on Embodied Freedom: Exploring the Intersections Between Christian Freedom and Personal, Social, and Global Bodies. The event was part of the ELCA’s commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, and one among many things related to it in which I am involved this year.

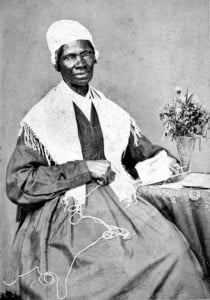

When Sojourner Truth queried, “… and ain’t I a woman?” in 1851, she called into question the racialization of womanhood that pervaded the nineteenth century and persists today. Being woman starts with a personal body that is inextricable from the political, which in this case means that the skin is raced and the politicized body is stratified accordingly. The freedom and limitations found in the embodied nature of being woman, ultimately holds intriguing resonance with Martin Luther’s 1520 claim of a paradoxical freedom inherent in being Christian:

“A Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none. A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.”

When Isabella Baumfree changed her name to Sojourner Truth, she was engaging in what Patricia Hill Collins calls “self-definition.” Collins says of Truth and other African American women throughout the generations:

“Their ideas and actions suggest that not only does a self-defined articulated Black women’s standpoint exist, but its presence has been essential to Black women’s survival.”

In a white racist society, Black women’s bodies have been commodified, objectified, and racialized. By claiming this embodied existence through what she calls an Afrocentric feminist standpoint theory, arguing that black women’s standpoint in this world affords them a distinctive view of the structures and processes that purport to limit them, Collins shows how black women are freed to challenge the very social constructs that exclude them.

The power of Sojourner Truth’s “ain’t I a woman?” query lies in the way it exposes the double standards applied to black women and white women when she spoke in 1851, what Collins calls the “contradictions inherent in blanket use of the term woman.” Because: “Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman?”

White women in 1851 were fighting to be seen and treated as equals to men, fighting for access and voice and vote. Black women were fighting to be seen as human, as women. And only a woman living in a black body would know – in with and through her body – that white women’s activism did not in fact include her.

Patricia Hill Collins details other ways that Truth claimed this category of “woman” for herself: “For those who question [her] femininity, she invokes her status as a mother of thirteen children ….” The fact that they were all sold into slavery speaks to a distinctive woman’s experience that no white woman in Akron, Ohio, in 1851 would ever know. Because of this, Collins concludes,

“Rather than accepting the existing assumptions about what a woman was and then trying to prove that she fit the standards, Truth challenged the very standards themselves.”

This deconstruction, self-definition, and claim of womanhood in a black body applies not only to this freed slave, but to the category of woman itself. She knew she was a woman, and she knew that those who said or inferred that she was not were wrong. Through her words and actions and through her body, she participated in breaking open assumptions and concepts that said she was not.

This paradox of embodied freedom is captured by Colson Whitehead in his Pulitzer and National Book Award-winning novel The Underground Railroad, particularly in a scene where the runaway slave Cora spends months in a cramped hiding space above an attic in North Carolina:

This paradox of embodied freedom is captured by Colson Whitehead in his Pulitzer and National Book Award-winning novel The Underground Railroad, particularly in a scene where the runaway slave Cora spends months in a cramped hiding space above an attic in North Carolina:

“What a world it is, Cora thought, that makes a living prison into your only haven. Was she out of bondage or in its web: how to describe the status of a runaway? Freedom was a thing that shifted as you looked at it, the way a forest is dense with trees up close but from outside, from the empty meadow, you see its true limits. Being free had nothing to do with chains or how much space you had. On the plantation, she was not free, but she moved unrestricted on its acres, tasting the air and tracing the summer stars. The place was big in its smallness. Here she was free of her master but slunk around a warren so tiny she couldn’t stand.” (179).

In “The Freedom of a Christian,” Luther understands the human person to have a twofold nature, spiritual and bodily, soul and flesh. This was central for his theological argument about the freedom conferred by grace and the proper role of works. The soul is free from having to earn salvation while the flesh is bound to serve the neighbor. The body, flesh and skin to be specific here, does not define a person and most importantly does not save a person, though it is a fact of this life.

In addition, Luther says we need not despise ceremonies, the things that our bodies do. We do need despise the false estimations and meanings ascribed to them, whether it be ceremonies, works, or the bodies themselves. Do not think that one hue of human flesh is better or worse than another, that color translates into merit and worth and value. Do not think that freedom of movement translates into freedom of the person.

Luther points out that “in the sight of men a man is made good or evil by his works…” and we can say that in the sight of a white racist patriarchal society, a woman is made good or evil by her skin color, her enfleshed body. It is our meaning-making processes that inscribe limits when it comes to the body.

Freedom isn’t found in abandoning the body, it is found in ascribing appropriate roles and meanings to it. Freedom comes when we integrate the flesh as part of a holistic vision of embodied freedom. “Look at my arm ….” Sojourner Truth implored. Look not just at the muscles in my arm bearing witness to a lifetime of labor, but look at the color and texture of its skin. “… and ain’t I a woman?”

Images via Embodied Freedom & wikimedia commons.