Is the only true way to deal with a homosexual inclination to “crucify” it? This is the question that has recently been raised at Crisis. Readers who are familiar with this debate will not be surprised to know that Crisis’ answer is “yes.”

I’d like to open my response by sharing the reaction of a friend of mine:

The problem with [this article] is that it seems to occupy a moral universe where the sole responsibility of the homosexual person is to crucify: crucify every thought, feeling, desire and passion. There’s no love, beauty, or relationship in this world view. Everything is suspect if you’re gay. This is why I find this writing so ‘triggering’, because after reading it one feels almost hopeless, and the truth is that the Church’s vision is so much more lovely, and so much more beautiful, and so much more hopeful.

– Aaron Saunderson-Cross

Aaron’s concern really gets at the nub of the problem. If our answer to LGBTQ people is “crucify your homosexual inclinations” and homosexual inclinations are identified as including our “desires for self-giving, for spousal relationship with another person, and for family itself,” then in effect what is being said is “you must crucify a large part of your personality, and most of your capacity to relate to other human beings.”

What does this look like? I understand that for some homosexuals it looks like a life lived as a “victim soul.” There are folks who embrace that kind of spirituality. They believe that their sexual orientation condemns them to a life of loneliness and continual self-denial, and they’re okay with that. And that’s fine.

To be honest, this is something that I can sympathize with and relate to – there is a kind of grim pleasure that one can take in the thought of a long, hard slog through the valley of the shadow of death. Sometimes you go through periods in life that are characterized mostly by forms of endurable but prolonged suffering and if you get into the right headspace that can actually be sort of appealing. You imagine your interior life as kind of a long siege, where all you have to do is hold out, stalwart until the reinforcements arrive. You gird up your loins, you tighten your belt, and you set your face like flint. It’s fun, in a way.

But it’s also exhausting. The Saints who express this kind of spirituality are generally the same ones that die young, often of complications related to their mortifications. Yes, there may occasionally be people who are called to this, just as there are occasionally people called to subsist for long periods on nothing but the Eucharist. But nobody would argue that every Christian who has a disordered appetite for ice-cream must therefore subsist entirely on locusts and honey.

Unless you have a very particular vocation, excessive self-mortification is actually a well-known spiritual danger. This is particularly true when the mortification is focused obsessively on a single aspect of your personality.

I experienced this myself. There was a period, a couple of years after I converted, where I bought into the idea that I had to crucify everything in my life or my personality that might pull me back towards “the world.” Mostly, this meant trying to crucify my feminism and my queerness. So, for example, I tried never to disagree with or contradict my husband in order to be humble and submissive. I wasn’t very successful at this, but I felt constantly guilty about my lack of success.

And I avoided anything gay. At its most extreme, I wouldn’t listen to Queen and felt conflicted about liking the Lord of the Rings movies when I knew that Ian McKellen was out and proud.

Instead of purifying me, this approach made me suspicious, judgmental towards others, paranoid about myself, scrupulous, and prone to despair. The myopic scrutiny to which I subjected my sexuality and gender made me negligent towards other aspects of my spiritual life. In straining to root out even the slightest strain of queerness from my personality, I completely failed to notice that more serious vices were taking root.

This is why we must be prudent. Pastoral care requires that we take into account all of the conditions that exist within the psyche, and that we allow the slow and painstaking processes of grace to bring forth holiness in a way that is appropriate to the individual. In a lot of cases, it’s necessary to leave imperfections alone because they are deeply intertwined with important, and fundamentally good, aspects of the self.

Christ elucidates this principle in the parable of the wheat and the tares. The servants in the parable ask if they should pull up the weeds that have been sown among the good seed, and the owner replies, “No…because while you are pulling the weeds, you may uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest. At that time I will tell the harvesters: First collect the weeds and tie them in bundles to be burned; then gather the wheat and bring it into my barn.’ ” (Matt 13:29-30)

Sometimes, imperfections in our personalities just have to wait for purgatory because there is no way of safely uprooting them now without destroying good fruit in the process. The roots are simply too badly entangled to separate them out.

This is, I think, very often the case with homoerotic desire. Just because a friendship is, in part, motivated by sexual attraction that does not mean that the friendship itself is necessarily unchaste or that it is therefore not a good thing. It means that the seed of friendship and the seed of lust grew up side by side – but provided it is the friendship, and not the lust, that is producing fruit, it’s just foolish to destroy good out of fear of evil.

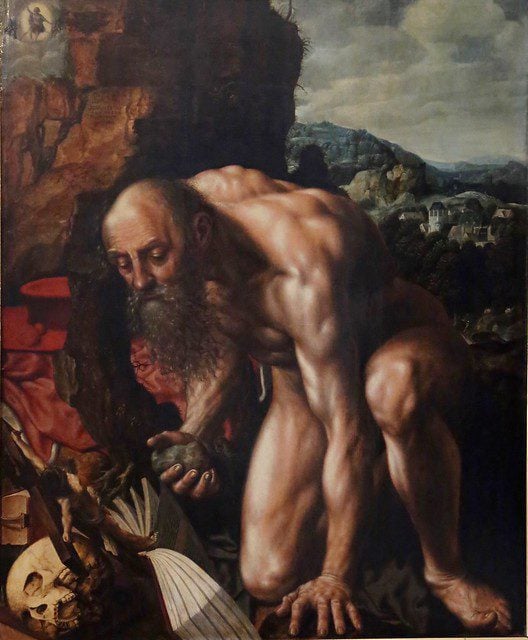

The same principle applies to works of art like Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam.” There’s no question, looking at this painting, that Michelangelo delights in the beauty of Adam, and anyone familiar with Michelangelo’s writings will be aware that this delight has a definite homoerotic basis. But the painting continues to haunt both the ceiling of the Pope’s chapel (not to mention the cover of many copies of John Paul II’s Theology of the Body) precisely because the work of art itself is good.

The problem with the call to simply crucify, crucify, crucify is that it demands that we put to death genuine goods – relationships, human touch, aesthetic experiences, etc. – out of a fear of anything that might be tainted by a disordered inclination. It gives evil veto power.

In doing so, it subjects the homosexual person to a hermeneutic of suspicion in which every friendship, every desire, every passion, every relationship, every moment of delight, is presumed concupiscent. It deprives God of the opportunity to perfect and transform our desires, to slowly burn away lust by the patient fire of divine love. Instead of calling us to submit humbly to the Cross as it is given to us, it calls us to take up nails, hammer and scourge and to become the agents of our own crucifixion.

Image credit: pixabay

Stay in touch! Like Catholic Authenticity on Facebook: