I’ve just finished reading Kristy Burmeister’s new book, “Act Normal”. It’s a memoir of her experience of being stalked by a schizophrenic member of her congregation, and of the aftermath of that trauma. Although she does eventually return to Christianity, her church community’s response drives her away, leaving her spiritually homeless for a number of years.

Basically, to boil it down, the elders of her church refused to take action to protect her. At first they deny that anything is going on. Then, when there is obvious physical evidence (a pair of her underwear left on a pew with a picture of her folded inside of it, letters with scriptural verses about burning whores, a bridal Barbie doll set on fire in her bed during a midnight break-in…) they insist that someone else must be to blame.

They dismiss the fact that there is a man who is obviously following this young girl, that he has a history of mental illness and domestic abuse, that the events follow a classic progression of stalking activity, that such cases almost always involve a male perpetrator, and that the police believe it is him (though they are unable to act due to functionally unenforceable anti-stalking laws). Instead the elders decide that the girls’ mother must be doing this to her daughter in order to frame the guy, for reasons that are ill-defined.

Ultimately, when the situation escalates to the point of blatant death threats, Burmeister’s family packs their bags and flees.

Burmeister’s story raises a question that it’s not able (for obvious reasons) to answer: how do we welcome people with severe mental illness without exposing others to danger. I’m not talking here about the common forms of mental illness, like depression, anxiety and OCD. Obviously there are a lot of mental illnesses that only pose a threat to the person who suffers from them. But some forms of mental illness can, under the right conditions, lead to violent or abusive behaviour.

It needs to be talked about in a Christian context specifically because Christian communities are often one of the only places in society where people with obvious, severe mental illness are welcomed socially.

In most cases, these are folks who live on the margins of society. They may have extremely repetitive behaviours, where it’s impossible to carry on a conversation because they just say the same thing over and over again. They might suffer from delusions that cause them to have constant crises over imaginary problems. They may have emotional regulation problems and have extreme reactions to triggers that nobody could possibly predict. They might have such severe anxiety that they are constantly monitoring the behaviour of others and voicing their concern over trivial or non-existent dangers.

Most people find it draining or intimidating to interact with people like this, so they just don’t. Churches are one of the few social settings where charity and patience are specifically practiced in a directed, communal way and where inclusion of the abandoned and the friendless is often seen as important community value.

In smaller congregations, especially, you’ll often find one or two people with severe mental or cognitive impairments who have been “adopted,” as it were, by someone in the congregation. This is actually a super important function that churches perform. Even in places with a robust safety net, people who have the kind of severe mental illness that impedes basic functioning are still at high risk of falling through the cracks.

Accessing social services often requires attending appointments (often at offices located in urban centers), filing paperwork and having a legal address. People who are disabled by mental illness often lack transportation, have poor executive functioning, fear government employees or the psychological establishment, don’t have stable housing or personal documentation and they may suffer from co-morbid depression or addictions that make it difficult or impossible for them to access public supports unless someone privately steps in and helps them out.

To make things worse, mental illness often runs in families and when it’s not being managed it can cause relationships to break down. So you end up with people who are completely socially isolated, not capable of caring for themselves, and paranoid about asking for help from professionals whose job it is to help them. If you do outreach to the homeless, you encounter these folks all the time.

Churches and Christian organizations are often the ones who step in, especially in rural communities, to help these folks get help. Christians who see the face of Christ in the “least of these” may be more willing to put in the time and effort required to earn a really difficult and paranoid person’s trust and Christian communities may be more willing to accept and welcome someone who really just isn’t able to function in other social settings.

Now, once you’ve adopted someone in this way, you naturally gain sympathy for them and for their perspective. You put in a lot of work and they become like family. In the majority of cases, this is a very great good, because in the majority of cases people with severe mental illness are not any more dangerous than people with anxiety disorders. They are rejected and outcast because of the challenges involved in befriending them, and the love of a Christian community can make the difference between a life of dignity and inclusion and a life of homelessness and addiction.

But what about the minority of cases in which a person’s mental illness does pose a threat to others?

In the same way that a mother does not want to believe that her violent child could actually do anything that bad, a Christian community may not want to accept that a person’s paranoid delusions or erotic obsessions make them genuinely dangerous.

This is what happened in Kristy’s case. Having taken in a man with schizophrenia, the elders of her church community did not want to believe that he was capable of sending death threats to an innocent girl, of obsessively stalking her and breaking into her house to set her belongings on fire. The problem was complicated by the fact that at least some members of the community also believed that they had “cured” his schizophrenia through prayer – and accepting that he was doing these things would have meant acknowledging that the miraculous healing had not actually taken place.

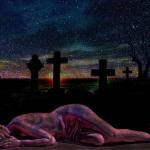

Image credit: pixabay

Stay in touch! Like Catholic Authenticity on Facebook: