A heretic is defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “a person who differs in opinion from established religious dogma.” Of course, that begs the question of, “Established religious dogma according to whom?”

A heretic is defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “a person who differs in opinion from established religious dogma.” Of course, that begs the question of, “Established religious dogma according to whom?”

In the Christian traditions, Roman Catholics say that dogma is established by the Roman Catholic church’s decrees and councils. The Orthodox Church says that dogma was established by the seven ecumenical councils held between 325 and 787. Protestants say that dogma is established primarily by the word of God. At the very least, all three traditions believe that the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed are basic standards of orthodoxy.

I have always been very careful about throwing around the words heresy and heretic. Those words are used way too quickly and frequently in debates, both in person but probably more frequently online, and are often just code for ‘someone who doesn’t agree with me.’ Still, the Bible calls out false teachers and therefore calling out false teachers seems to be at least one aspect of what it means to be a faithful church leader today.

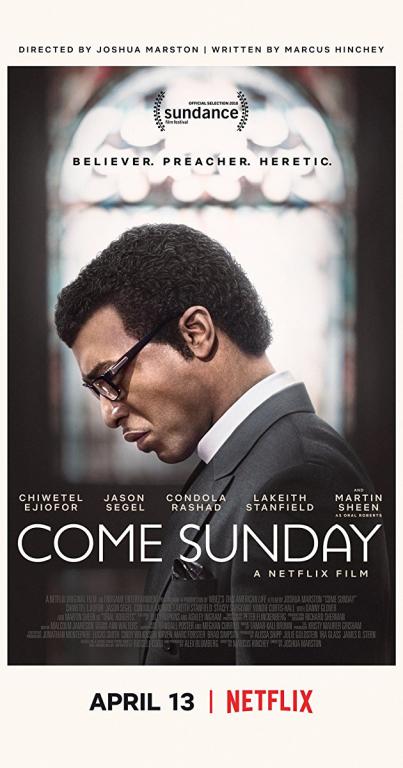

‘Heretic’ was the name of a story broadcast on the NPR show This American Life in 2005 about the crisis of faith that Pentecostal Bishop Carlton Pearson went through in the late 1990s. A new Netflix film, Come Sunday, is based on the NPR show, liberally quoting from it, and from Pearson’s life.

The crisis of faith that Bishop Pearson (as he’s referred to in the film) went through is a fairly common one for many people, and a similar story could have been told about Rob Bell and probably Brian Mclaren. Confronting the news about a genocide in another country, along with coming to grips with his unbelieving uncle’s suicide, Pearson begins to question how a loving God could send somebody to hell. As he wrestles with his previous beliefs about the afterlife and passages such as 1 John 2:2 and Romans 5:18, Pearson believes that he hears the voice of God saying that people don’t need to be saved, because they already are saved. Essentially, Bishop Pearson became a universalist, a position he still holds, by all accounts, today as he ministers at All Souls Unitarian Church in Tulsa, OK.

The way that the film treats these new beliefs is interesting. Though it seems to have been made by those outside the Christian community, it is respectful of Christian faith. The film doesn’t set up obvious good guys or clear bad guys, but has empathy for all the main players, from Pearson (Chiwetel Ejiofor) and his wife (Condola Rashad) to his mentor Oral Roberts (Martin Sheen) and his assistant pastor Henry (Jason Segel) who leaves Pearson to start a new church. In the end, the film certainly sides with Pearson, but shows the difficult toll his theological change made on him, as well as on those around him.

The problem with universalism, the idea that there is no hell and everyone is going to be saved, is that it has no respect for human choices. As G.K. Chesterton wrote, “Hell is God’s great compliment to the reality of human freedom and the dignity of human choice.” It also completely undermines the work that Jesus came to do. After all, if we’re all fine, why would Jesus have to come to earth, be put under the law and be put to death? If we’re all going to heaven, why would Jesus say that we must be born again to see the kingdom of God? If sin has no eternal consequences, why would the Bible be so explicit about the dire need of justification for sinners before God? And, as a few different characters in this film say, if there is no hell or punishment in the next life, why would the Bible talk about hell and punishment so much?

Sheen’s Oral Roberts speaks clearly but sympathetically to Pearson in a memorable scene, “[Your teaching that everyone is saved] is heresy. Are you certain it is God’s voice you heard?… Satan is a snake and he chose to speak through you.” Roberts distances himself from his protege Pearson, but holds out an olive branch, that if Pearson will repudiate his false teaching, then there will be a place for him at Oral Roberts University. Pearson cannot go back on what he believes God has told him so he is, in effect, shunned by the charismatic evangelical community in which he had been a star. However, since that time, he has found some measure of new fame in the liberal mainline church and on shows like The Edge with Paula Zahn and Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher.

The confessions of the church objectively show that Carlton Pearson is guilty of heresy, that he has stepped outside of the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints. That doesn’t mean that his story is not worth watching. Come Sunday is a thought-provoking film that asks us to walk a mile in the shoes of a conflicted man and to consider whether and how we should judge him. It’s not as easy as the heresy hunters on the internet would have you believe.