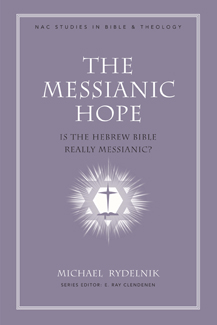

In reading Michael Rydelnik’s The Messianic Hope, one can’t quite help but see the effect of Enlightenment ideals upon modern critical scholarship. Interestingly, the primary concern isn’t liberal scholarship, but the growing tendency within conservative Evangelical scholarship to deny a strictly Messianic interpretation of many key Old Testament texts. While this does not indicate all of these scholars are denying a Messianic understanding of the text, Rydelnik’s concern is the detraction from a clear Messianic understanding to the original audience: the prophet delivering oracular (and later, written) revelation to God’s covenant people.

The Content:

Chapter 1 introduces the reader to the purpose of why Messianic prophecy is important. What is unique to this chapter is not simply the admonition of Rydelnik from Luke 24:44, but the perspective he brings to this study as a Messianic Jew. For Rydelnik, understanding the role of direct Messianic fulfillment is deeply personal. Growing up in an Orthodox Jewish home, he witnessed his father divorce his mother over her conversion to the Christian faith. Rydelnik, seeking to disprove his mother’s newfound faith, went to the Hebrew Scriptures, only to find they indeed spoke of the Messiah, Jesus Christ.

Chapter 2 addresses how modern interpreters approach the Old Testament’s Messianic prophecy. In this section, he deals respectively with Historical Fulfillment, Dual Fulfillment, Typical Fulfillment, Progressive Fulfillment, Relecture Fulfillment, “Midrash” or “Peshur” Fulfillment. While he acknowledges there are various other interpretive methods, these are the most common found in Evangelical scholarship.

Chapters 3-7 yield evidence to defending his thesis that direct prophetic fulfillment of the Messiah is the most frequent form of interpretation that should be seen. Chapter 3 deals with text-critical evidence, espousing that variant texts supporting the Messianic reading are to be preferred over the MT. Chapter 4 builds the case by examining innerbiblical evidence, namely, to display that later biblical authors read the former as Messianic.

Chapter 5 present canonical evidence to display the united theme of the closed Hebrew canon to reveal a Messianic understanding in the specific shaping of the canon, as well as the books included. Chapter 6 brings New Testament evidence to display that the NT writers and Christ believed the OT writers knew they were writing about the coming Messiah, rather than the NT authors adding a more full, inspired Messianic meaning to OT prophecy. Chapter 7 explores the hermeneutical principles of the NT in regard to understanding messianic prophecy; not all examples are direct fulfillment – thus, it is important for us to take note of these principles in order to see Christ in the OT.

Chapter 8 is devoted to trace the influence of Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki (otherwise known as Rashi) from his own time, the Reformers, and our current day. Most notably, Rydelnik builds the case that Rashi intentionally interpreted direct messianic passages in an anti-messianic fashion in order to dissuade Jews from believing in Yeshua.

Chapters 9-11 focus on key messianic texts, including Gen. 3:15, Isa. 7:14, 52:13-53:12, and the book of Psalms (namely Psalm 110). Genesis 3:15 he regards as Protoevangelium, that is, the “first gospel” account between the promised seed of the woman who will crush the head of the snake. From the prophets (Isa.) he critically defends reading the Hebrew almah as “virgin”, rather than “young maiden” and for the messianic interpretation of the passage rather than historical fulfillment. In using Psalm 110, Rydelnik again views this to be a messianic passage referring to the future King who will reign forever upon the throne of David.

Finally, in chapter 12 Rydelnik issues a plea to return to a messianic understanding of the Hebrew Bible, as this is the intended, historic meaning of the text.

Why Does This All Matter?

In anything we are studying, we ought to ask the simple question: what impact does this have upon the church? What are the natural consequences of rejecting a Messianic interpretation outright (Historical Fulfillment), holding to a Sensus Plenior interpretation (Dual Fulfillment), a Progressive Fulfillment, and so forth? Are there weaknesses for the argument of a Direct Fulfillment interpretation of these passages?

While I have generally viewed the discussed passages as inherently Messianic, it is troublesome for more than a few reasons to see many leaving these interpretations behind. One of the most problematic inferences to this would seem to pose an unintended detriment to scripture’s perspicuity. If the scriptures are clear in matters of Messianic expectation to us, it would seem self-evident that they should be so for those whom first heard the promises of God regarding Christ. The potential drawback to refraining from understanding the direct fulfillment of Isaiah 7 can easily lead to a slippery slope, failing to uphold the virgin birth of Christ. Many may claim this to be an overstatement – yet hermeneutically, we have seen this departure take place in more than one account of scholars who have espoused this view.

Beyond this, to assume the NT authors utilized creative exegesis to arrive at their conclusions emphasizes the inability for one to understand the text as it should be understood. I understand there are difficulties in arriving at the same conclusions regarding some of the NT usage of OT texts as messianic fulfillment, yet it would seem that this is not a hermeneutical problem of the NT authors. The problem of understanding is within us.

Final Thoughts on the Book:

While there were some things I could not fully get behind in Rydelnik’s treatment (such as Isa. 7:13-15 and v. 16 depicting another child other than the Messiah), the book was absolutely phenomenal. Within the footnotes is a treasure trove of information that the reader would be foolish to bypass; they are there for a reason. The format of the chapters and overall layout of the book is excellent and easy to follow, thus, it made for pleasurable reading.

There are difficult parts to follow if one doesn’t have a thorough background in the original languages (especially in dealing with text critical issues in why the MT should not be followed in certain passages) – yet it is not detrimental to understanding the breadth of his argument. I feel this work is pertinent to our time, as some Evangelical scholars are embracing more liberal treatments of the text and supplanting their own definition to particular doctrines (take for example, Blomberg’s current stance on inerrancy). It is an incredibly important topic, especially with regard to how we understand the revelation of Christ in the focus of redemptive history.

I would fully recommend this book.

Disclosure: I received this book free from Baker Academic through the media reviewer program. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.