With “The Gospel According to St. Matthew,” we looked at one of cinema’s most straightforward adaptations of the Christ story. With “Jesus Christ Superstar,” we come to one of the more unorthodox.

Where Pasolini’s film was sparse and no-frills, “Jesus Christ Superstar” is frantic and loud, fueled by music from Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice’s popular rock opera. Those wanting a clear look at who Jesus was will likely walk away confused — the Christ on display here is elusive, mysterious and confounding. Norman Jewison’s 1973 film is less concerned with fidelity to the original text and more fascinated by the reactions every one seemed to have to Christ. Some loved him, some were frustrated by him and many eventually killed him. What was it about him that made it impossible to walk away with a neutral response, and why is that story still celebrated 2,000 years later?

“Jesus Christ Superstar” is a fascinating take on the gospel story, even as it deviates from the biblical narrative and ventures into some theologically questionable waters. It’s told with energy and passion, powered by fantastic music and constantly finding new ways to breathe fresh life into the story.

In fact, it doesn’t even really take place in Christ’s lifetime. As the overture plays, Jewison opens with shots of ancient ruins in the Israeli desert. A bus pulls up and a caravan of actors emerge, quickly gathering all of their props, putting on makeup and getting into costume. The movie is full of anachronisms — not just the 1970s rock music. The dialogue is pure 70s, from the song “What’s the buzz?” to the cry of “Hey J.C., J.C. you’re alright by me” in “Hosanna,” the song sang during the Triumphal Entry. The musical filters the Christ story through a modern lens — it’s not just interested in what happened, but in how the people surrounding Christ may have felt and how we can relate to them today.

The music, a fusion of 70s rock, disco, ballads and R&B, enlivens a story that’s been told so many times that it’s in danger of feeling staid. It brings emotion to a tale whose tellers are often more focused on faithfulness to the biblical narrative and theological orthodoxy than on emotional impact. But Christianity involves a heart response to who Christ is, so it’s essential to remember that the people who encountered him were emotionally affected by him in one way or another. It’s hard to identify with their fears, frustrations, hopes and dreams through a straightforward retelling of the story; “Jesus Christ Superstar” gets to the hearts of the people whose decisions led one week to the Triumphal Entry and the next to a crucifixion at Golgotha.

The Pharisees, for instance, are scheming, obsessed with power and not letting Roman opposition ruin the system they’ve worked so hard to keep in place; Jesus’ death is a means to keep the status quo in their favor. Jesus’ earliest followers are as a mix of revolutionaries and hippies, some wanting just to enjoy being part of the circus that follows Jesus around and others wanting to ride into Jerusalem with swords blazing; when he refuses to conform to their image, those same people rally with the Pharisees to crucify him. Even the majority of the apostles just want to relax in the garden, write their books and achieve the fame that comes from studying at the feet of a popular rabbi. Everyone has their own desire for what Christ should do for them and their own hopes for what he’ll be — a revolutionary, a scapegoat, a great rabbi. In one of the film’s goofiest but most amusing moments, King Herod, at Christ’s trial, simply wants to see a magician. If Pasolini’s film focused on the broken humans around Christ looking for someone to give them hope, “Jesus Christ Superstar” looks at people who either didn’t know what to make of Jesus or wanted to use him as a means to an end, and lashed out when he wouldn’t fit into their plans.

Mary Magdalene (Yvonne Elliman) is probably the most sympathetic of Christ’s followers in this movie. As tradition — but not necessarily scripture — holds to, she is a former prostitute whose life was changed after encountering Jesus. We meet her rubbing Jesus’ face with oil and ointment, wiping his feet and face with her hair. The sensuality of the scene is a bit startling, as is the infatuation she has with Christ — but this account is in the Bible, and because we’ve heard the story so many times we often don’t realize what a scandal it probably was for her to not only pour expensive perfume on Christ’s feet but also to do something so tender and, yes, intimate. Mary seems mystified by Jesus, but confused because the love he requests isn’t the same that other men have demanded of her. Her standout song “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” is an aching, poignant reminder of how much we’ve cheapened the concept of love and how much purer — and more demanding — Christ revealed it to be.

More fascinating is the role of Judas, played by Carl Anderson in the film’s best performance. Aside from Peter — who has his denial moment — most of the disciples are largely ignored. But Judas is the first character we see onscreen, presented much differently than in the Gospel stories. We meet him just as he’s decided to turn against Christ, afraid that his good ideas have evolved into something insane and dangerous.

We don’t learn much in the Bible about Judas Iscariot. We know that he was one of the 12 disciples, but not even the only one named Judas. He was in control of the money purse. And he was the one who betrayed Jesus with a kiss. He’s usually portrayed in art as scheming and money-grubbing, ready to sell out his savior for 30 silver coins at a moment’s notice. And it wasn’t until thinking about Anderson’s portrayal here that I began to wonder how wrong we might have it.

After all, the men Jesus called to follow him likely had good intentions at the start. Do we really know that Judas started following Christ because he wanted to sell him out? Was he always the “trouble disciple” on the outer fringes — the fact that he identified Christ with a kiss in Gethsemane speaks to the fact that he had a closeness with Christ. And while it’s generally accepted that John was Christ’s closest friend, who’s to say that Judas wasn’t close to him as well? And even if he wasn’t, and this is all artistic conjecture, it’s a fascinating way to get into the maligned disciple’s head and try to understand why someone who followed Jesus for so long would betray him.

Judas is a tragic figure, one who cares deeply for Jesus but who also wants to save his own skin. He signed on to follow a man who would give to the poor and help the sick–not one who was going to upset the status quo, claim to be God and challenge the religious rulers. When it comes time for Judas to collaborate with the Pharisees, he’s all excuses and justification, not even wanting to take the money offered to him because he believes he’s doing a right thing; but, of course, it drives him to suicide when he sees that he’s sentenced an innocent man to die.

Everyone in this movie sees Jesus in a different light — a threat, a deluded leader, a potential revolutionary, a caring friend. The superstar of the title is a man whose presence affects everyone around them — he challenges leaders, moves sinners to repent, frustrates those who hope he’ll help them get ahead. And by not showing Christ performing any miracles and not giving us a great deal of insight into his mind, the film focuses on people’s responses to Christ and his claims of deity. This is a movie not about people reacting to Christ specifically but to their idea of who he is and what they expect him to be. When he doesn’t meet with those expectations — indeed, seems more than willing to crush them — they’re either left confused or they lash out. After all, you don’t crucify someone who says they want to help people; you crucify someone when they claim godhood and call you not to power, but to service.

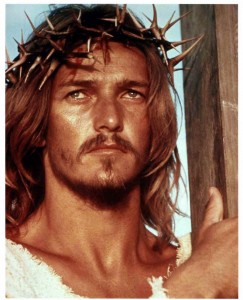

As Jesus, Ted Neeley is a bit perplexing. It’s not just that he fits the Western mentality of a blue-eyed, blonde haired Jesus. It’s that there’s something a bit too wispy and even weak about him. There’s so much fervor and energy throughout the film that it’s surprising to hear Neeley’s high voice and still mannerisms when we first meet Jesus. It bothered me upon my first viewing, but now I find his performance spot on. Everyone expected Christ to be a revolutionary, a teacher with power. But they didn’t expect his meekness and kindness. He seems almost blindsided by the love he has for people, and overwhelmed by the amount of need surrounding him, and I find Neeley’s work affecting and moving, arresting through its meekness.

His standout moment is “Gethsemane,” when Jesus prays to the Father to let him avoid crucifixion. While one could quibble with the scene’s theology, the song is powerful and angry, capturing the intense anguish the Bible describes Christ feeling in the garden at that moment, which the Bible says caused his sweat to become like blood. And in that moment, Neeley captures the authority and control Christ had over his fate — the Bible repeatedly states that Christ was fully aware where his life was heading and that he was in control of the moment he would lay it down.

The film’s finale is intriguing and, I suspect, frustrating to many followers of Christ. After the crucifixion, the acting troupe tears down the sets and gets back into the van. There’s a sense of resignation to them. And we’re left with the film’s final shot — the empty cross. There’s no resurrection; just a shot of a shepherd leading his sheep through the desert as a metaphor.

I can see why some might find it frustrating, but I think it’s actually the perfect ending for a film about people’s reactions to Christ. After all, if this is the story everyone has been telling for years, and if Jesus had such an impact on the people he encountered, than whether that cross was the end of the story — or if the shepherd does still lead his people — is of utmost importance. Is Christ’s story one of tragedy — a charismatic leader killed at a young age by his followers? Or is it one of triumph and hope? The film’s final song, “Superstar,” sung by Judas and interposed with scenes of the crucifixion, poses that question:

“Jesus Christ, who are you, what have you sacrificed? … Jesus Christ Superstar, do you think you’re what they say you are?”

By not giving us a resurrection — and, in fact, not really showing us any of Christ’s miracles — the question is left open-ended for the audience. Was his story tragic or was it triumphal? Why is it still told if it’s the story of a man deserted by his followers and executed by the state? And if there is something true to it, then isn’t it worth paying attention to? Everyone who encountered Christ had to come to a decision point of what they were going to do about him. And those of us who are his followers today realize that he’s not a man you can encounter and be left lukewarm on.

This is the second part in my Lent 2016 series, The Road to Easter, where I write about a movie about the life of Christ every Sunday. Previous entries can be found below: