A few weeks ago, Pope Francis made news for spontaneously embracing a severely disfigured man named Vinicio Riva during a public audience at the Vatican.

According to CNN, Riva, “has long been accustomed to the unkindness of strangers. He suffers from a non-infectious genetic disease, neurofibromatosis type 1. It has left him completely covered from head to toe with growths, swellings and itchy sores.”

The reason the picture became so popular worldwide is that it demonstrated that Pope Francis was looking at Riva through the compassionate and loving eyes of Jesus, an ability that’s much easier to preach about than practice. Riva himself was shocked by the embrace, admitting, “I felt a great warmth.”

Since then, he has become emboldened by this transformative act of love: “I feel stronger and happier. I feel I can move ahead because the Lord is protecting me.”

A Unique Burden

I was reminded of Riva when I began reading best-selling author Dean Koontz’s latest novel, “Innocence.” Its main character and narrator, Addison, is a young man for whom the unkindness of strangers (and even family members) is the norm.

I was reminded of Riva when I began reading best-selling author Dean Koontz’s latest novel, “Innocence.” Its main character and narrator, Addison, is a young man for whom the unkindness of strangers (and even family members) is the norm.

Addison says, “When I entered the world, the twenty-year-old daughter of the midwife fled the bedroom in fright…When the midwife tried to smother me in the birthing blanket, my mother, although weakened by a difficult labor, drew a handgun from a nightstand drawer and, with a threat, saved me from being murdered.”

Though Addison loved his mother, she could barely tolerate being around him. He observed, “She tried hard to love me, and to an extent she did. But I was a unique burden.”

Shortly after his eighth birthday, Addison’s mother sent him away from their home in the woods and told him never to return. Having lived a solitary life thus far, he was surprised and scared when people who saw him reacted to him so violently that they wanted to kill him.

After making his way to the city, Addison crossed paths with a grown man whose nature he shared: “By the standards of humanity, we were exceedingly ugly in a way that excited in them abhorrence and the most terrible rage.”

As the only person who’d ever shown Addison unconditional love and acceptance, the boy came to call this man Father. Together, they lived underground for 12 years in an area far below the city that no one knew existed. Father taught Addison to never feel bitter about the treatment they received in the outside world.

That lesson proved especially important after Father was murdered by two men who spotted him during one of his infrequent forays above ground. Addison was left orphaned, having no human contact for six years and realizing “there is sorrow baked into the clay and stone of which the world is made.”

And yet, Addison yearned for more from life: “Books had shown me, however, that all people everywhere wanted their lives to have purpose and meaning. This longing was universal. Even I, in my terrible difference, wanted nothing less than purpose and meaning.”

A New Hope

One December day, Addison meets Gwyneth, a young woman trying to escape from the man who murdered her father and tried to rape her. Addison’s intuition tells him that Gwyneth is different: “Always I had remained hopeful that, among the millions on this Earth, there might be a few who could summon the courage to know me for what I am and have the self-confidence to still walk part of this life with me. The girl, mysterious in her own right, was the first in a long time who seemed as if she might have that capacity.”

Together, they embark on an adventure that involves a heroic homeless man, a degenerate and sadistic art thief, holy and unholy men of the cloth, and even demonic marionettes. But as usual with Koontz’s novels, there is a lot more to the story than the individual pieces. In fact, there are examples of light in the darkness influenced by the author’s deeply Catholic worldview and theology.

Love, Power, Hope and Beauty

Koontz’s keen understanding of human nature, love and hate, good and evil, and the supernatural world makes him one of the wisest and insightful writers of our modern era. In one instance, he takes on shallow, selfish understandings of love and points the reader toward a mysterious, higher, divine love.

Addison, reflecting on his feelings for Gwyneth, says: “Love is absorbing, related to affection but stronger, full of appreciation – and delight in – the other person, marked by a desire always to please and benefit her or him, always to smooth the loved one’s way through the roughness of the days and to do everything possible to make him or her feel profoundly valued. All of that I had experienced before, and this was all those things but also a new and poignant yearning of my soul toward some excellence that this girl embodied, not just physical beauty, in fact not physical beauty at all, but something more precious that she epitomized, although I couldn’t name it.”

On the other end of the equation, Koontz comments on evil in the human heart through Gwyneth’s observations about the man who killed her father: “Ryan Telford has a reputation, respectability, much education, a prestigious position, but under all that….it’s about the same thing – power. Having power over others, to tell you what to do, to take what you have, to use you any way they wish, to demean you and break you and make you obey, and finally to rob you of your faith in truth, make you despair that there’s no hope and never was…Everyone talks about justice, but there can be no justice where there is no truth, and there are times when truth is seldom recognized and often despised.”

Though hope is a regular feature in Koontz’s novels and is present in “Innocence,” I’d have to qualify it as a tempered hope. The world in the book is basically our world in which more and more people indulge their self-absorbed, greedy, perverse passions instead of gravitating toward a higher good. These people may not be the majority, but they don’t need to be because their evil acts generate outward to touch many beyond their small circle, either intentionally or unintentionally. Koontz likely sees what’s going on in the world and is simply reflecting that in his work as a caution about how the sins or virtues we choose produce consequences that can’t always be corrected. Though God and “good” are assured of final victory, the road to that victory may be strewn with innocent victims.

Despite the horrors experienced by characters in this book – and if you’re fainthearted, be aware that the violence, while not graphically described, is brutal nonetheless – Koontz reserves the possibility of redemption for all his characters, as evidenced by Gwyneth informing Telford with a Flannery O’Connor-esque turn of phrase, “You can still save yourself. There’s always time to save yourself until there’s no time left.”

Koontz also conveys his own appreciation of beauty through Addison’s observations: “Through the stillness, snow fell not in skeins but in infinitely layered arabesques…laying boas on the limbs of leafless trees, ermine collars on the tops of walls, a grace of softness in a hard world. You might have thought it would fall forever, endlessly beautifying all it touched, except for the reminder of the river. When the snowflakes met the undulant water, they ceased to exist. Everything and everyone we treasure in this world comes to an end. I loved the world not for itself but for the marvelous gift it was, and my only hope against eventual despair was to love something larger than the world…”

Author, Philosopher, Theologian

One of the strengths of “Innocence” is that the direction it takes in its final quarter took me completely by surprise. It’s not a ‘deus ex machina’ situation in which the ending comes out of nowhere; Koontz plants the seeds and weaves the threads throughout. I just never saw all the pieces of the puzzle coming together the way they do – and that surprise is always a delight to a reader.

The ending includes elements that should resonate with Catholic audiences in particular. But I’m reluctant to say too much because there’s nothing like the joy of discovering the truth yourself.

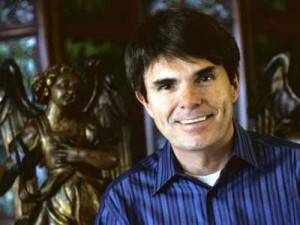

Though Dean Koontz is described as an author who’s sold a gazillion books, maybe he should also add philosopher and theologian to his credits. He has long been a champion of the disabled and infirm in his work, challenging society’s movement toward euthanasia and its tendency to say that certain people’s lives are not worth living.

Though Dean Koontz is described as an author who’s sold a gazillion books, maybe he should also add philosopher and theologian to his credits. He has long been a champion of the disabled and infirm in his work, challenging society’s movement toward euthanasia and its tendency to say that certain people’s lives are not worth living.

In this story, he creates a new kind of outcast who leaves us remembering that the choices we make have consequences both in this world and the next – and that it’s important to take an honest look at our own, less-visible disabilities so we can raise ourselves up toward who God wants us to be.

Much like Pope Francis, Koontz views “the least of these” with a Christ-like vision. It’s a vision that he conveys with a wealth of heart and spiritual depth in novels like “Innocence.” It’s a vision that can put us each on a better path if we pay attention to it.