The vivid, imaginal world of my childhood oscillated between two kinds of mythology: the great, epic Celtic legends told to me by my grandfather, whom I called, Daddy Jim, that involved Cúchulainn, Fionn MacCumhaill, Oisín, Niamh Chinn Óir and the Lochlannaigh, on the one hand; and on the other hand, Cowboys and Indians, courtesy of the Saturday morning children’s matinees in Cork City’s movie theatres.

But while the Celtic myths made me feel proud, the matinees frustrated me. I was continually annoyed by the portrayal of the Indians as stupid, painted savages who simply circumnavigated the encircled wagons waiting to be picked off by the sharp-shooting Whites.

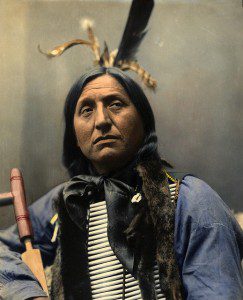

My matinee heroes were not John Wayne, Gene Autry or Roy Rogers but Cochise, Geronimo, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. When we re-enacted these battles as kids, I always insisted on being an Indian and it was a point of honor, not just for egoic reasons, to be the last man left standing. This was the beginning of a life-long passion for social justice.

A while ago, I was trekking in the forest near my home in Tír na nÓg outside the little town of Healdsburg, when I stumbled upon a Caol Áit (a Thin Place) and got sucked into a time warp. At the other end of this “tunnel”, I found myself in a strange location watching two men angrily facing off, one an “Indian” and the other a “Cowboy”. I could see inside their psyches and read their minds.

The “Indian” was a very athletic brave fuming at the indignities that had been visited upon his people by the Pale Faced invaders. He was spoiling for a fight, and his nemesis, the “Cowboy”, gave him an ideal opportunity. Meanwhile the “Cowboy” grinned smugly, totally secure in the knowledge that his six-shooter was more than a match for this “savage’s” tomahawk.

As I watched, a dignified, wrinkled elder took the brave aside and said, “You have to think of the long-term consequences of your actions. If you injure this man, his people will come in hordes and kill our men, women and children. I want you, instead, to go on a Vision Quest and see what the Great Spirit has to tell you.”

The brave reluctantly agreed and, following the time-honored custom of his tribe, spent the next ten days in the wilderness, alone and fasting. And indeed the Great Spirit did speak to him in a series of inner visions that rocked him to the core of his being. He saw, in graphic detail, his previous three incarnations and he wept in shame.

In one he had been a conquistador, arrogantly oppressing the native population. In the second one, he had been a member of the US cavalry, pushing the Indians into more and more inhospitable and resource-less reservations. And in the last-before-the-present incarnation, he had been a bounty hunter, making a killing, literally, from the scalps of the Indians, which he sold to the authorities who were committed to ridding the continent of these “varmints”. His greed was stoked and his cruelty disguised by the “patriotism” of general Philip Sheridan who declared, in 1869, that “the only good Indians I ever saw were dead.”

The young brave sobbed uncontrollably for several hours. Then he asked the Great Spirit, “Is that why I chose to be an Indian in this present incarnation?” The Great Spirit nodded. The brave realized then that he had simply swapped one set of prejudices for another. He saw that his anger came from the sleepwalking of being unaware of his past lifetimes and of his present mission – which was to develop compassion and forgiveness for the human condition.

Meanwhile the “Cowboy” had taken a very bad fall from his horse and was clinically dead for about 20 minutes. During this time he had a Near Death Experience: the tunnel, the white light, the mentor, the life review. He, too, was rocked to the core of his soul. He recovered the memories of his last three incarnations, in each of which he had been a Plain’s Indian, suffering unspeakably at the hands of the Whites.

At the end of the third lifetime, his mentor had asked him, “How well do you think you’d handle being a White with greater numbers and superior technology? Do you think you’d use these advantages compassionately? Or would you simply forget?” He obviously had forgotten. After three lifetimes of being oppressed, he had just as mindlessly been an oppressor, despising and hunting “his own people” of the three incarnations just past.

He cried bitter tears of contrition. And it was the tears that revived and awakened him; that and the taste of cool water on his lips from the cupped hands of the brave who was kneeling at his side, shielding his face from the blazing sun and his defenseless body from the circling coyotes.

Two pairs of eyes embraced in complete love; two souls recognized each other; two brothers separated by incarnation had been re-united by remembering.

My vision ended. I stepped back through the Caol Áit and found a madrona tree. Sitting under its generous shade, I wondered, “Where do my prejudices come from? What task did I set myself for this incarnation? Why have I been asleep?” The tears flowed silently – and my dog, Kayla, licked them lovingly from my face.