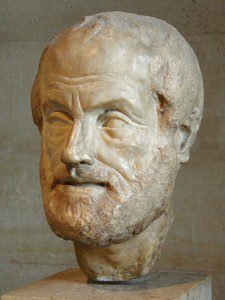

The principles of logic have been formalized since at least his day, and there’s much to be learned from and about them.

A critic of the Church, writing last night, has faulted a list of scholars formerly associated with the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies and/or the subsequent Maxwell Institute because they’re all Latter-day Saints.

It’s not the first time I’ve seen such a thing. Nor even the hundredth time. This dismissal, on this basis, is very common among a certain type of critic.

So I’m going to cut to the chase. Arguments — and I use the term here as scholars and logicians typically do, to refer to orderly presentations of evidence intended to support propositions, not to mere “disagreements,” let alone to “fights” — are properly assessed on the basis of two elements:

1) Is the adduced evidence solid, and adequately representative of the situation?

2) Is it arranged according to the principles of sound logic?

They aren’t properly evaluated on the basis of who made them.

Thus, if Polyneices says “All men are mortal, and Socrates is a man, so, therefore, Socrates is mortal,” it doesn’t matter whether Polyneices is a Mormon, or a Jew, or Black, or an adulterer, or a saint, or a serial killer, or an undertaker with a personal financial interest in the mortality of Socrates. It doesn’t matter whether his assertion has been peer reviewed, whether it’s been published in the prestigious Journal of Truths Acceptable to the Fashionable Elite, or whether it’s merely been inscribed into a watermelon using a dull Swiss Army knife. What matters is whether or not all men really are mortal, whether Socrates really is a man, and whether the logical syllogism “All A are C, B is a member of the set of A, therefore B is C” is logically valid. It is, by the way: The conclusion follows from the premises, and the premises are true. If the argument is going to be overturned, that will require disputing either the truth of the premises or the validity of the logic. Pointing to Polyneices’s movie preferences, or his hot temper, or his poor taste in shoes, or his bad hair, would be perfectly irrelevant.

By the same token, if Alexandros says “All cacti are mammals, and Paris is in Germany, so, accordingly, Shakespeare is Thailand’s greatest architect,” that argument will be, um, problematic even if it passed peer review and was published in the Academic Journal Greater than All Other Academic Journals. Even if Alexandros holds views that most high-status folks share on religion and politics. And even if a poll of professors of dentistry shows that virtually all orthodontists, whether in North America or Europe, endorse it. Why? Because its premises are factually false — cacti aren’t mammals, and Paris isn’t in Germany — and because its logic is invalid. (“All A are B, C is D, therefore E is F” is a thunderously, screamingly, invalid logical form.)

To pronounce an argument dismissible solely because its author is Jewish, or Catholic, or Republican, or White, or even ugly and unpleasant (i.e., yours truly) is an instance of the ad hominem logical fallacy — which, despite common misconceptions to the contrary, isn’t about being nasty. It’s about focusing on irrelevancies. (Which may explain why it’s often classified as a “fallacy of irrelevance.”) To dismiss an argument because it wasn’t published in the Right Kind of journal is similarly irrelevant. An argument can be sound even without being published at all. In fact, all sound published arguments were, prior to publication, originally sound unpublished arguments. (Duh.)

I addressed several of the recurring objections to the scholarly legitimacy of the publications of FARMS (e.g., concerning peer review) back in 2006, in an article entitled “The Witchcraft Paradigm: On Claims to ‘Second Sight’ by People Who Say It Doesn’t Exist.” These objections still recur, of course, although now they’re often focused on the Interpreter Foundation (FARMS having since been absorbed into the Maxwell Institute, which has now set its face resolutely against publishing the sorts of things that once generated controversy — and attention, and, in a way, general relevance — for it.) But I stand by what I wrote in that article, and I encourage those who want to quarrel with me on these matters to read it first. We’ll all save time that way.