Day in, day out, I’m going through the manuscript:

Change was inevitable. The subject peoples began, slowly, to convert to Islam. There were good reasons for this, of course. Being Muslim was the key to social advancement. Even more tangibly, converts escaped the dhimmi taxes imposed by Islam upon non-Muslims in order to support the military and other institutions from which non-Muslims were exempt. (Such escape was permitted only after considerable Umayyad resistance. Far from forcing conversions, the Umayyads demonstrated by their resistance that they were actually more concerned about money, about fiscal revenues, than they were about the souls of their subjects.)

The old distinctions between Arabs and non-Arabs began to break down. In a sense, the Umayyads, with their old Arab notions, were being left behind by history. A new generation of Arabs was growing up in the provinces, a generation that had never seen Arabia. The new Arabs gradually ceased to be occupying troops. They sent down roots into the soil of Iraq or Egypt or Syria or North Africa and became a ruling class with local interests. They began to resemble the old landlords of the eastern Mediterranean and Iranian culture areas and began to function like the old local aristocracies.

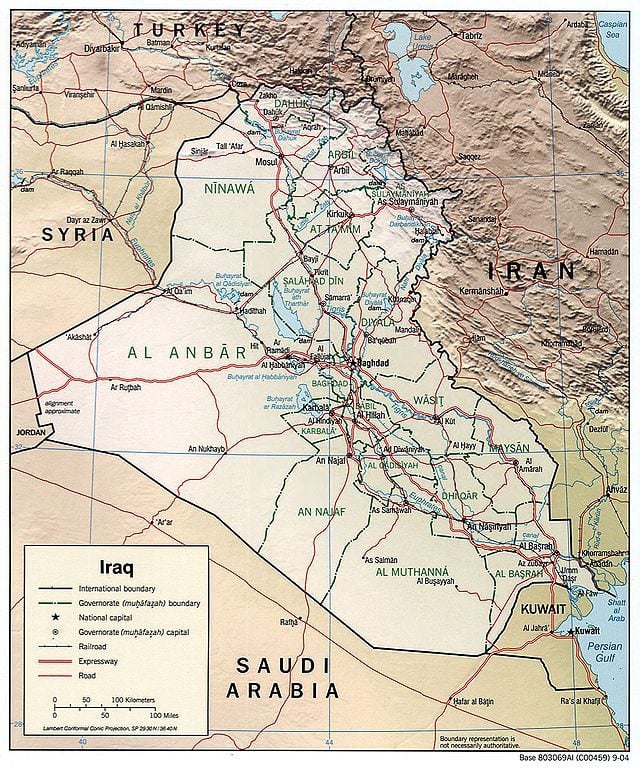

There was movement from the other side as well. Attracted by the concentration of wealth in the Arab garrison camps, local merchants and craftsmen moved out to them, learned Arabic, and converted to Islam. (This explains how the military camps of Basra and Kufa, in Iraq, and Fustat in Egypt eventually grew into actual cities.)[1] A whole Islamicate society was developing in which those who spoke Arabic (especially if they were Muslims) were privileged politically, economically, intellectually, and socially. The old notion of Islam as a religion for the Arabs survived for a considerable time, however, and resulted in a practice which is of some interest from a Latter-day Saint perspective: In order for a Persian or a native Syrian to be accepted as a Muslim, it was not enough simply to convert to Islam. In the Umayyad period, he or she also had to be affiliated with one of the old Arab tribes. Converts thus became mawali (“clients”) of Arab tribes and were, in effect, adopted into them. This was a practice that had existed in pre-Islamic Arabia, by which a person would be given fictional descent from the same founder of the tribe (who was sometimes himself fictional) to whom all the other members traced their genealogy. Eventually, the distinction between the person’s fictional genealogy and his real genetic lineage would be forgotten, and he would be considered a full member of the tribe.

[1] Grossly oversimplifying, Fustat became today’s Cairo.