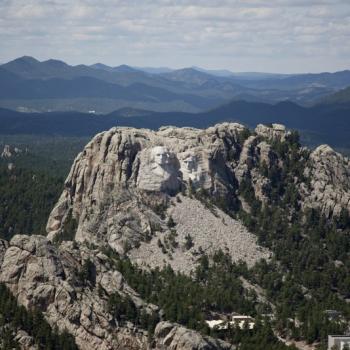

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Educated at Princeton University and trained at Harvard Medical School, Lewis Thomas served as dean of Yale Medical School and the New York University School of Medicine and then as president of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center prior to his death in 1993. Somehow, though, he found the time to write a great many very fine essays that were gathered into such books as Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher, and The Medusa and the Snail — and to win the National Book Award three times.

Here are some passages from his 1992 volume The Fragile Species:

There is [a] feature of [the] level of oxygen that seems to me . . . remarkable: it stabilized at its present level around 400 million years ago, and it seems to be fixed there. It is a lucky thing for us, and for the life of the earth, that it did stabilize at that concentration. If it were to increase by more than two percentage points, most of the planet would ignite. If it were to decrease a few points, most of the life would suffocate. It is nicely balanced, against all hazards, at an absolutely optimal level.

Other gases in the atmosphere, including carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and methane, also seem to have been regulated and stabilized over long periods of time at optimal concentrations, despite the constant intervention of natural forces tending to push them up or down. (118-119)

How it is regulated so that the methane concentrations are everywhere fixed and stable is not known, but it is known that if the level were to decrease appreciably the concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere would begin to rise to hazardous levels. (119)

[T]he surest, unmistakable evidence of coherent life, all of a piece, is its astonishing skill in maintaining the stability and equilibrium of the constituents of its atmosphere, most spectacularly and improbably the fixed levels of oxygen and, pace us, CO2, the pH and salinity of its oceans, the diversity and developmental novelty of its kingdoms of live components, the vast wiring diagram that maintains the interconnectedness and interdependence of all its numberless parts, and the ultimate product of the life: more and more information.

One thing eludes me, always has and likely always will: If the earth is what I think it is, an immense being, intact and coherent, does it have a mind? If it does, what is it thinking? We like to tell each other these days, in our hubris, that we are the thinking part, the earth’s awareness of itself; without us and our marvelous brains, even the universe would not exist — we form it and all the particles of its structure, and without us on the scene the whole affair would pop off in the old random disorder. (191)

[M]y friends will object to the word “mind,” worrying that I am proposing something mystical, a governor of the earth’s affairs, a Presence, something in charge, issuing orders to this part or that, running the place.

Not a bit of it, or maybe only a little bit. (192)