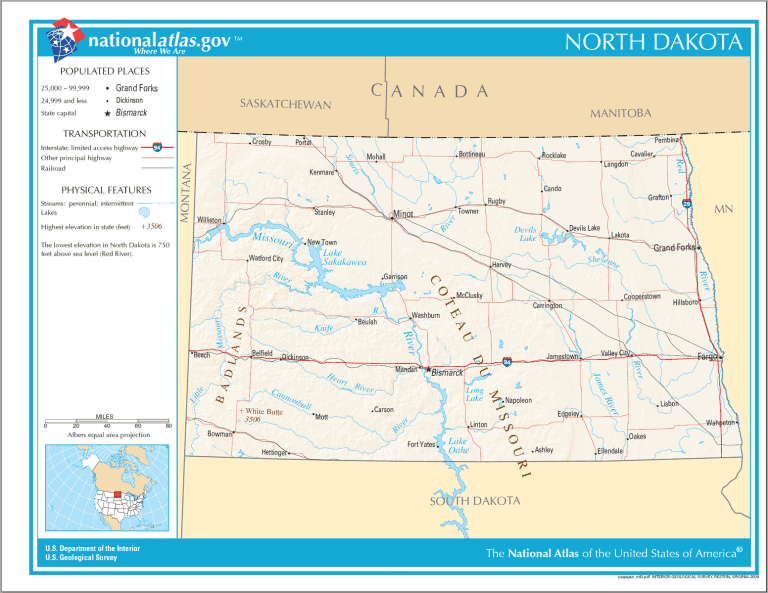

My father grew up on an isolated farm outside the tiny, unincorporated town of Garske, Ramsey County, North Dakota, in the upper right hand corner of the state. When the time came for him to attend high school, he was obliged to board with relatives in the comparatively large town of Devils Lake, the county seat, which was located roughly fifteen or twenty miles away. (In the late 1920s, in a remote and rural area very few cars and lacking good roads, a distance of fifteen to twenty miles was considerably further away, practically speaking, than it is today.)

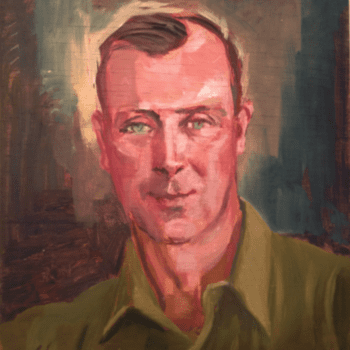

My grandfather — my father’s father — was Danish, though he grew up in America. My grandmother had arrived in the United States from Norway at the age of eighteen.

She was a fairly strict Lutheran, in her way, and she taught her children, including my father (whom she actually wanted, at least for a brief while, to study for the Lutheran ministry) that swearing would send them to Hell.

This posed a problem for my Dad. One of his duties on the family farm was to milk the cows. (His father’s rule was that the boys could stay up as late as they wanted — so long as they were up before dawn to attend to their milking duties. That put a natural brake on their propensity to be adolescent night owls.)

Anyway, as a boy, my father was convinced that it was impossible — simply, literally, impossible — to milk cows without swearing. They would invariably hit you in the face with their indescribably filthy tails. Or, alternatively, just when you had filled the milk bucket, they would kick it over, or plant an incredibly filthy foot in it. So you simply had to swear. And they were so stupid, he said, that swearing was the only language that they could understand.

This worried him. Was he bound for Hell?

But then, when he went off to Devils Lake to stay with his “city cousins,” the theological problem of evil became even more acute for him:

Because they lived in the city rather than on a farm, of course, his cousins never had to milk cows. Which meant that they didn’t need to swear. Therefore, it seemed to him, salvation depended upon geography. Because they had grown up in a town, his cousins had a very good chance of going to Heaven. By contrast, though, and solely because he had had the misfortune of being raised on a farm, my father was fated to be damned.

Thus did the theological problem of evil begin to weigh upon the mind of a young North Dakota boy in the late 1920s.

Posted from Seaside, Oregon