(Tuxyso / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bill Hamblin and I published the column below in the Deseret News for 21 August 2015:

There is something instinctive in us that causes us to stand in awe before the majesty of nature. In the earliest known forms of religion, the veneration of natural beauty, fecundity and power held a central place in the hearts of mankind. All great polytheistic religions have gods and goddesses associated with the powers of nature. Rain, fertility, storms, rivers, mountains, oceans, earthquakes and volcanoes were all associated with gods and goddesses.

Ancient art is, in many ways, fundamentally an attempt, however inadequate, to imitate the power and beauty of the great artist’s manifold achievements in nature.

For many ancient religions, all nature was infused not only with life but also with divine power. For the Romans, whatever moved had “anima,” or soul. Hence, our term “animal” derived from “anima”; anything that moved was “animate” — possessed of “anima.”

Animals were obviously animate, but so, too, were plants, which not only moved in the breeze but also by growing, and hence had anima/souls. The flowing of a river made it animate. The heavens, planets and stars moved, and the names of all of our planets are still those of animate Roman gods. More rarely, even the earth moved — for example, in earthquakes and volcanoes. Hence, all nature was “soul-full” — full of anima/soul. Non-moving things were “in-animate” — that is, lacking in anima. When you die, movement ceases, for your anima/soul has departed.

A part of this nearly universal human religious belief of seeing the divine in nature is the association of mountains with the home of the gods. Mountains are the largest things in nature, with their peaks seeming to ascend into the heavens. Scripture is filled with sacred mountains where man encounters God: Moses on Sinai (Exodus), Nephi’s vision on a high mountain (1 Nephi 16:30, 17:7, 18:3), and the brother of Jared on Mount Shelem (Ether 3:1).

Many ancient peoples believed that their gods dwelt upon the top of a majestic mountain — the idea of the Mountain of the Lord, found in the Bible, is a nearly universal belief. Zeus dwelt upon Mount Olympus, Baal of the Canaanites upon Mount Zaphon. The Hindu gods found their abode on Mount Meru.

Somewhat paradoxically, a canyon is in many ways an inverse mountain, and one of the greatest canyons in the world, the Grand Canyon, has evoked a sense of awe since the first Native Americans gazed upon it in wonder. As the Colorado River and its tributaries cut their meandering paths through northern Arizona over millions of years, those rivers created a sequence of mountains all lying within the vast depth beneath the rim of the canyon.

Most visitors to the canyon today don’t realize that, in addition to the magnificent geological vistas, they also encounter a mini-catalog of world mythology. Many of the early canyon geologists, such as Clarence Dutton (1841-1912), applied mythological names to the prominent mountain peaks within the canyon, seeing in the grandeur of the canyon the sacred mountains and temples of the gods and goddesses of mythology.

The Greek and Roman gods are represented with temples to Jupiter, Apollo and Diana, the goddess of the hunt, which stand somewhat incongruously beside Solomon’s Temple. Most readers are perhaps unaware that the Viking paradise of the gods is actually found in the Grand Canyon, on Walhalla (Valhalla) Plateau — where these words were actually written at sunset. Nearby, Wotan (Odin) sits enthroned. England’s medieval mythology is represented, with King Arthur’s Castle nestled beside the Holy Grail Temple.

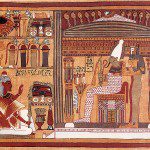

But early geologists went beyond Western mythological traditions. The Egyptian gods are clustered in temples to Isis, Osiris, Horus and the Tower of Set. Nor is Asia’s mythology neglected. Hindus have temples to their “trinity” of Vishnu, Brahma and Shiva, as well as a shrine to Rama, one of the legendary incarnations of the god Vishnu and the hero of the great Hindu “Ramayana.” Even preeminent philosopher-prophets such as Confucius, the Buddha of India and the Persian Zoroaster receive temples.

Much of this is merely fanciful. But in a sense, the Grand Canyon is transformed into a mythological paradise for all of the gods, dwelling harmoniously in their temples upon their own sacred mountains. This poetic mythos of the Grand Canyon reminds us that the mechanistic interpretations of modern science need not destroy the sacred mystery of the cosmos, and that we, like our ancient ancestors, can still see divine power manifest in nature and in natural wonders like the Grand Canyon.