Arthur C. Brooks, of the American Enterprise Institute, is a hero of mine. Here are some excellent remarks that he delivered at the BYU graduation services just a few days ago. Please watch. They last less than twelve minutes:

This is the sort of thing — our current tendency to withdraw into mutually contemptuous, mutually uncommunicating, mutually demonizing “communities” — that I had in mind some weeks ago with my little blog entry “Infected with Doubt” and its reference to the so-called “Incel subculture.” Some responses to that blog entry illustrated my point precisely.

I’ve intended to return to that subject a bit but, thus far, have been distracted from doing so by other things.

***

Here’s a Deseret News column that I wrote about some of Dr. Brooks’s work — on a rather distinct subject — all the way back in 2012:

One of the most interesting and provocative social analysts in America today is Arthur Brooks, currently president of the American Enterprise Institute.

In his 2006 book “Who Really Cares,” Dr. Brooks summarized scores of academic studies demonstrating that religious people give far more to charity — even to non-religious charities — than do the non-religious. They’re also more likely to volunteer to serve with such charities, as well as to assist family and friends, to donate blood, to give food or money to homeless people on the street, and even to return change mistakenly given to them by a cashier.

Faithless acquaintances have assured me all my life that religious believers concentrate on “pie in the sky when we die,” while they and their fellow secularists focus on improving life in the here and now.

In any particular case, of course, this may be true. On average, though, the supposed contrast is apparently quite false.

In 2008, Brooks followed up with “Gross National Happiness.” I don’t especially like that title, but it’s a very stimulating book. Brooks first discusses the value and accuracy of self-reporting in social surveys. Then, drawing once again on his wide reading in the relevant sociological literature, he presents his case for what makes us happy and what doesn’t.

I can’t reproduce the nuances or convey the richness of Brooks’ data in a newspaper column, but I summarize a few highlights from just one relatively short chapter:

Religious people of all faiths are, on average, markedly happier than secularists, and this is true even when wealth, age and education are taken into account. In one major survey, 23 percent of secularists reported being “very happy” with their lives, versus 43 percent of religious respondents. Believers are a third more likely to express optimism about the future. Unbelievers are almost twice as likely as the religious to say, “I’m inclined to feel I’m a failure.”

In 2004, 36 percent of those who prayed every day said they were “very happy,” while only 21 percent of those who never prayed said so.

Data from 1998 reveal that people who were certain that God exists were a third more likely to describe themselves as “very happy” than those who denied his existence. Curiously, agnostics were more gloomy than atheists; only 12 percent of agnostics surveyed claimed to be very happy. People who asserted that there was “little truth in any religion” were roughly half as likely to assert a high degree of happiness as those who believed that religion contains significant truth.

Believers in life after death are about a third more likely than nonbelievers to call themselves “very happy.” By contrast, people who say that we don’t survive death are three-quarters more likely to say that they aren’t very happy.

Correcting for other cultural factors and comparing apples with apples, people who live in religious communities also fare better financially than do those who live in relatively secular communities. Brooks cites an economist who investigated the effect on one’s income when others in one’s community are religiously active. For instance, he measured how the church attendance of Italian-American Catholics affected the incomes of African-American Protestants in the same neighborhood. His conclusion? The more your neighbors go to church, the more you will tend to prosper. This is probably because of the cultural benefits that accrue to a community as a whole when a significant proportion of the community follows typical religious standards: There’s likely, for example, to be less divorce and drug abuse — both of which cause economic woes. And such influence in a community attracts like-minded people into a neighborhood, thus improving it further.

An advocate of greater secularism might concede that religious fantasies provide a helpful crutch for stupid, ignorant and/or irrational people, whereas better educated and more honest unbelievers face reality without such comfort.

A 2004 study, however, showed that religious adults were a third less likely than secular adults to lack a high school diploma, and a third more likely to have at least one college degree. Given two people, one of whom has a college degree and one of whom doesn’t, but who earn the same salary and are identical in age, gender, race and political views, the college graduate will be 7 percent more likely to be a churchgoer.

Secularizing writers often like to imagine how much better the world would be without religion. They should pray that they don’t get their wish.

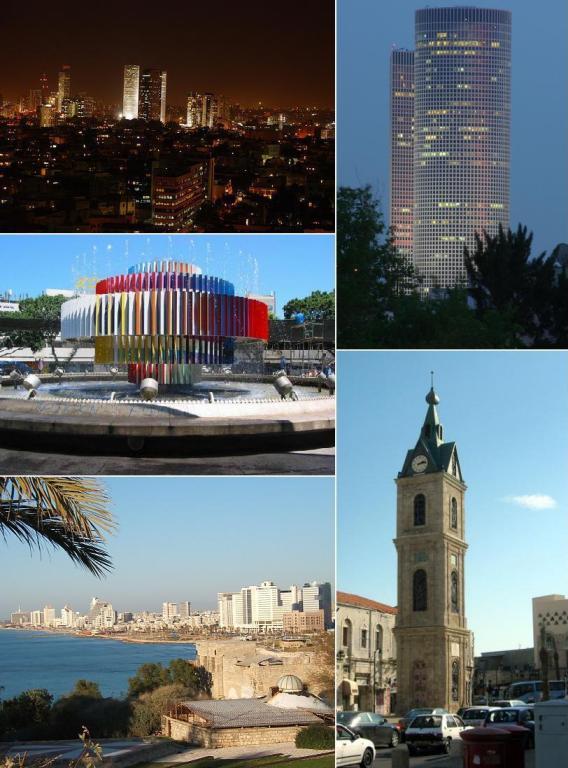

Posted from Tel Aviv, Israel