I first posted this blog entry on 14 September 2017. Because of some recent exchanges, I think it advisable to repost it:

A reader of this blog who is deeply alienated from Mormonism and, I think, from theism generally, has posed an important question in a comment. I think it’s worth replying to his challenge in an actual blog entry, rather than merely in the “comments section.” He is responding to my recent description of myself — one of many such self-descriptions — as leaning strongly libertarian on economic issues:

When I saw the “economic libertarian” declaration, I began to formulate the wrestling I wanted to have with you, Daniel, and with those who are similarly pro-freedom, like my own father. I had wrestled for years inside my own mind on why so many Mormons believe in this economic libertarianism, and yet on Sunday sing “In a world where sorrow ever will be known, where are found the needy, and the sad, and lone . . .” and here comes my question. If not by government mandate, than what mechanism would you use, Daniel and others, to show your empathy and kindness and love to the sad and lone, only on Sunday in singing a hymn? Here we are at Sic et Non on a religious website called Patheos debating how to be kind to others, and how relieve the loneliness, and yet we are talking of beliefs in unlimited freedom? I’ve been to hell and back in my own mind on this and similar questions, having lived as good a Mormon life as any, both during the week and on Sunday, using Mormonism as my guide, and yet I find my father, and much of my Mormon family, in direct opposition to Jesus on so-called social issues like this one. In the world of letting all businesses do what they want, where is the motivation to do good and be kind? If in religion only, then here we are in religion right now, and we’re still causing sadness and loneliness because . . . God?

First, a preliminary note:

Since I don’t believe that Jesus said anything programmatic at all on questions about labor regulation, public ownership of the means of production, tax policy, the ideal scope of the state, or the like, I don’t grant the premise that any particular sort of economic policy position can be described as “in direct opposition to Jesus on . . . social issues” like these. Many years ago, when Rev. Jerry Falwell was preaching about “the biblical position” on the then-proposed Panama Canal Treaty, I thought he was abusing the scriptures. My reaction today is just the same when I hear leftists insinuating that socialism or the minimum wage is mandated by the teachings of Jesus and, in exactly the same way, when I hear folks on the right seeming to suggest that there is a single gospel position on corporate tax rates or on the personal income tax.

I do believe that there are some basic moral principles that need to be kept in mind — the preservation of human freedom being a bedrock one — but, on the whole, most matters of public policy are issues on which decent, reasonable people of good will can (and do) differ. I hope that they can differ without demonizing each other, civilly.

I’m committed to free markets principally for moral reasons, because I believe in freedom.

Moreover, I do not believe that the people who run the State are intrinsically wiser or inevitably more virtuous than are people outside of government. Indeed, one might argue, given the track record of governments since, say, 1900, that the evidence strongly leans to the contrary: Governments have killed scores and scores of millions of people — in wars, yes, but also, amazingly, in peacetime and among their own citizens. (Think not just of the Third Reich, but of the Soviet Gulag, North Vietnamese reeducation camps, the Cambodian “killing fields,” and Mao’s “cultural revolution.”) They’ve created famines, too, either deliberately (as in the Ukrainian terror-famine of 1932-1933) or, more commonly, through incompetence and indifference (as in Ethiopia and Eritrea and in today’s North Korea).

Governments, especially unelected ones, need not please their customers. They enjoy a monopoly of force, and can (and do) compel support. In free and voluntary exchanges, by contrast, no party to the exchange can coerce. Each seeks to obtain something from the other and, if a bargain is successfully struck, each gives something that it values less in order to obtain something that it values more. Both parties win.

A couple of specific examples will make this much less abstract:

You have a refrigerator. I have cash in the amount of x. If we make the trade, it’s because I value my cash less than I value your refrigerator, and you value your refrigerator less than you value my cash. Each of us gets something we want at a price that we’re willing to pay.

The same thing goes for exchanges of labor: You value a certain amount of time and effort less than I value the repair of my car. I want my car repaired and am willing to hand money over for it. You want my money more than you want to nap. Accordingly, I pay you a certain amount of money that we’ve agreed upon, and we both emerge from the transaction having gained from it.

The brilliant Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith, generally considered the founder of economics, understood this well and expressed it memorably in his classic 1776 book The Wealth of Nations:

In almost every other race of animals each individual, when it is grown up to maturity, is entirely independent, and in its natural state has occasion for the assistance of no other living creature. But man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can interest their self-love in his favour, and show them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them. Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages. (The Wealth of Nations 1:2:2)

The genius of free markets is that they harness human self-interest, even greed, and make it work for the welfare of others.

Thieves, who are greedy and self-interested, simply take what they want, whether by stealth or by force. People in business, however, know that, on the whole, they must produce goods and services that other people desire (cars, mowed lawns, computers, ocean cruises, televisions, novels, movies, doughnuts, or gourmet meals) in order to get what they want.

As Adam Smith put it, describing a typical tradesman or businessman:

He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. . . . [H]e intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was not part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it. (The Wealth of Nations 4:2:9)

As I say, my principal commitment to free markets and voluntary exchange is a moral one. But it’s deeply gratifying to know that free markets offer the most fundamentally powerful way to alleviate poverty, as this 4:40-minute video explains:

“If You Hate Poverty, You Should Love Capitalism”

So I reject as a false dilemma the idea that singing “In a world where sorrow ever will be known, where are found the needy, and the sad, and lone . . .” on Sunday while believing in economic libertarianism indicates hypocritical inconsistency. And I absolutely deny that the only or even the best solution for sorrow, need, sadness, and loneliness is a “government mandate.”

Seriously? Are government bureaucrats, functionaries of the State, really better at comforting the sorrowful and easing the sadness of the lonely than family and clergy and good neighbors are?

And how good is the government, really, even in alleviating tangible, material want?

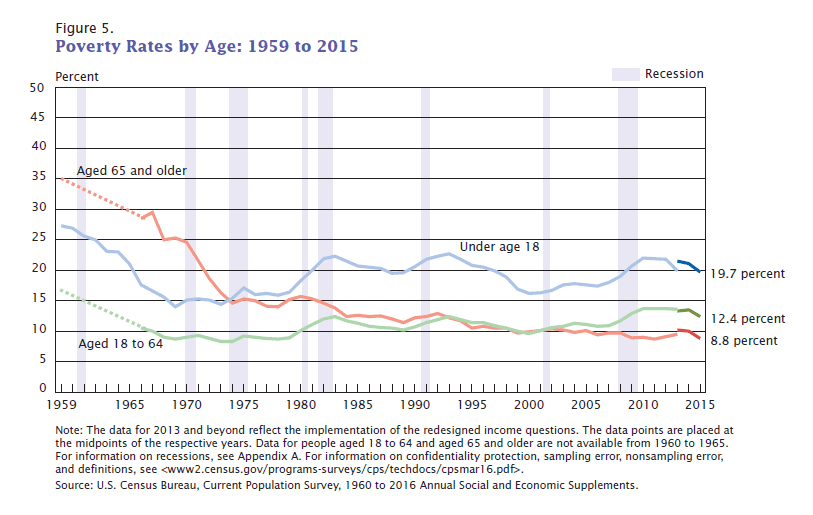

President Lyndon B. Johnson announced the “War on Poverty” in January 1964. As the chart below indicates, the poverty rate for the large majority of American adults, those between ages eighteen and sixty-four, seems to have been dropping rather sharply from 1959 until then, but hasn’t changed a great deal since, despite billions upon billions upon billions of dollars given out as welfare:

Of course, measuring poverty (or even defining it) is notoriously difficult, as is eliminating it. Poverty among the elderly seems to have improved considerably (at least, from 1959 to about 1973 or 1974), but it’s not clear why. Social Security was already in place well before 1959. Perhaps it’s a result of better and more widespread pension plans. But what’s striking about the above chart generally is the relatively stable (if not increasing) overall poverty rate since the inception of the government’s “War on Poverty.” If nothing else, this should demonstrate that a naïve faith in the efficacy of government for eliminating poverty needs to be nuanced a bit, to become somewhat more realistic.

Now, I’m neither naïve nor stupid enough to believe that free capitalistic exchanges will eliminate all suffering, erase all poverty, ward off all catastrophes. There are, certainly, situations in which charitable aid is required, and, in such cases, such aid is obligatory for Christian disciples (and others) in a position to give it. Sometimes, surely — as with the recent hurricanes in Texas and Florida — government assistance is essential.

But my questioner asks a directly personal question: “What mechanism would you use, Daniel and others, to show your empathy and kindness and love to the sad and lone, only on Sunday in singing a hymn?”

And I answer it directly and personally: Like other Latter-day Saints (and others not of our faith), my wife and I contribute in various ways to help. Not least among those ways are contributions to the LDS Fast Offering Fund and the LDS Humanitarian Aid Fund and the Perpetual Education Fund. (I feel more than a bit awkward about writing of such things, since we strongly prefer to keep these matters confidential, but the question deserves a specific answer.) We’ve given, recently, directly to two specific families impacted by Hurricane Harvey and, again, to the LDS Humanitarian Aid Fund. For at least a couple of years now, I’ve pushed (and we’ve given to) the Liahona Children’s Foundation. (I wish we could give more.) And we try, as well, to do non-monetary things for those within our orbit who are sad or lonely.

My questioner asks, with regard to those of us who believe in free markets and voluntary economic exchanges, “where is the motivation to do good and be kind?” I answer that such motivation is where it has always been, in fundamental human nature, in the commandments of God, and in the whisperings of the Spirit (even to those who don’t recognize such whisperings for what they are). It is unjust and untrue to suggest that people who believe in freedom can’t simultaneously be good and kind, let alone believe in goodness and kindness.

Well. That’s a rather quick and inadequate response, but it suggests the general lines of my reaction to my reader’s challenge.