I published this little item in the Provo Daily Herald back on 20 October 1999. Considerable history has come and gone since then. For example, Rudy Giuliani became “America’s Mayor” a little less than two years later amid the catastrophes of 9-11 and, since then, has become a national embarrassment:

Blasphemous Art in Brooklyn Stirs Controversy

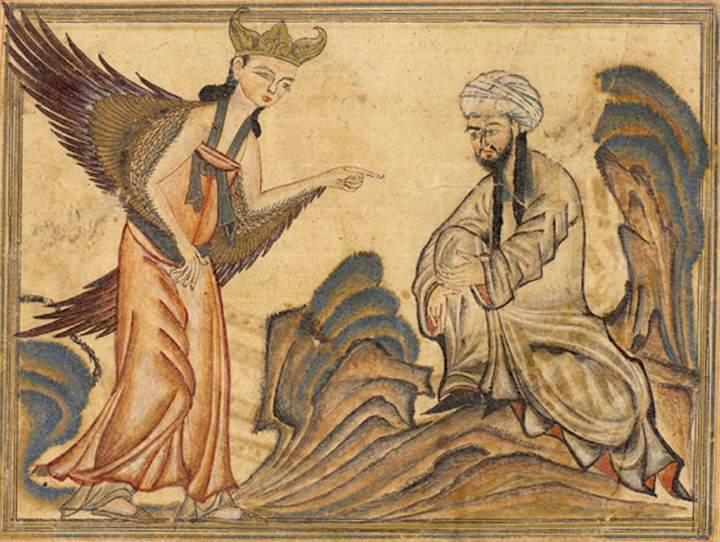

Religious controversies about art are hardly new. Michelangelo’s depiction of nude figures on the Sistine Chapel caused a scandal; so, presumably, did Akhenaton’s eccentric innovations in ancient Egypt. Some iconoclastic religions find blasphemous the very act of creating religious art. Until recently the most notorious modern case of artistic blasphemy was Andres Serrano’s vulgarly titled 1989 depiction of a crucifix immersed in a jar of urine. (Would the art critics who praised Serrano’s work have been equally enthralled with a depiction of the corpse of Martin Luther King, similarly submerged and titled?)

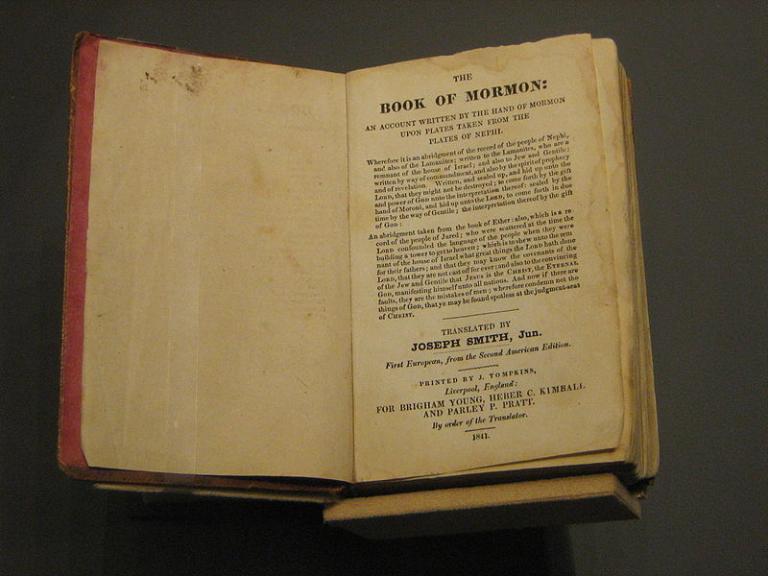

An artistic and religious controversy at New York’s Brooklyn Museum has again brought this issue to the forefront of public attention. The museum is currently displaying Chris Ofili’s “Holy Virgin Mary,” an abstract portrait studded with preserved animal genitals and elephant dung. Naturally, Catholics and many others have found this offensive, blasphemous, and without artistic merit. New York mayor Rudy Giuliani has threatened to cut seven million dollars of museum funding if the portrait is not removed. Supporters of the artist and the museum have denounced his threat, claiming it violates constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech.

But does government refusal to fund a particular work of art deny freedom of speech? In reality, for every artist the government subsidizes in some way, hundreds receive no subsidy. Since its resources are limited while the amount of potential art is essentially unlimited, government must necessarily choose which artists to subsidize and which not to subsidize.

Who, then, decides which specific art works receive these limited government subsidies? Should such decisions be left exclusively to museum directors and the art establishment? Do their unique skills and insights allow them to transcend the need for public scrutiny or accountability? There is, in fact, no consensus in the art establishment as to what constitutes art, let alone what constitutes “good” art. One prominent national art museum recently displayed the following three masterpieces: a canvas painted completely black, a string of light bulbs hung on a wall, and a circle of stones on the floor. That such nonsense can pass among museum directors for serious art suggests legitimate grounds (at least) for outsiders to question their aesthetic judgment.

A government subsidy means taxpayers are patronizing the art. If a patron asked an artist to paint a naturalistic portrait of his daughter in her wedding dress, and the artist returned with an abstract nude painting of the bride smeared with elephant dung, it is doubtful that the patron would pay the artist. And he would have every right not to do so. He bears no constitutional obligation to pay. Unless one is willing to argue that the patron of a work of art should have no say about the type and quality of art produced, the people whose government patronizes art with their taxes should likewise be allowed to decide which specific art should receive subsidies.

But the Brooklyn controversy raises another equally important issue—a religious one. The First Amendment states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This means, first, that the government may not create state-sponsored religions (as are found, for example, in many European countries). Second, if the government does patronize religion, it should give all faiths equal treatment. Thus, when the government provides chaplains for the armed services, it allows clergy of all religions to serve.

As a corollary to these two ideas, it seems clear that government should not be involved in attacking the beliefs of any particular religion. To do so implicitly establishes those religions not critiqued as superior to the religion that is. For the state to sponsor art that, by Roman Catholic standards, is clearly blasphemous, is to establish non-Catholic religions as superior to Catholicism. Thus, Mayor Giuliani has it exactly right: “You don’t have a [First Amendment] right to government subsidy for desecrating somebody else’s religion.”

While the First Amendment clearly states that the government cannot prevent blasphemous art from being created, sold, or exhibited, it seems equally clear that government should not be involved in subsidizing blasphemous art. If it does so, it is implicitly (and illegitimately) establishing certain religious ideas as superior to others.