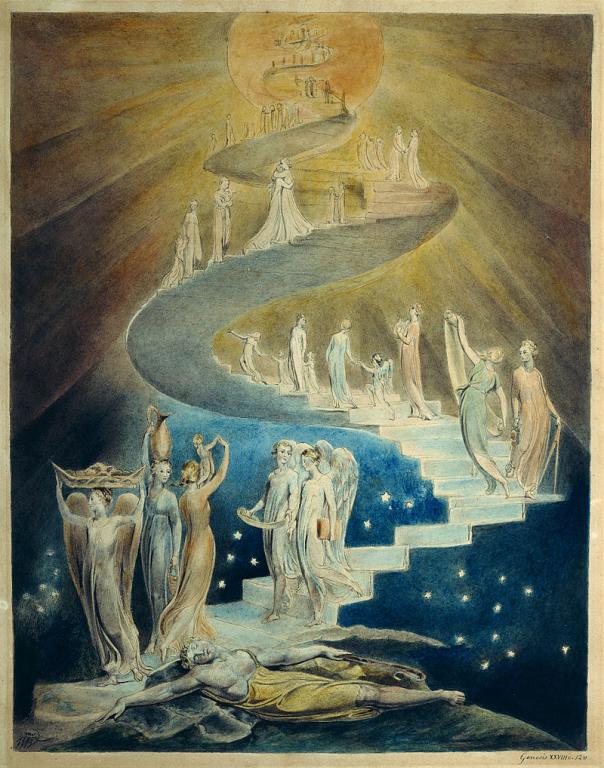

Wikimedia Commons public domain image

A recurring theme in the texts that we’ve been reading in my Islamic philosophy class — particularly, I think, in the Faṣl al-Maqāl (“The Decisive Treatise”) of Ibn Rushd and in Ibn Ṭufayl’s Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān (“Alive, Son of Awake”) — is the notion that the real theological and philosophical truth should be restricted only to the elite and that it should be carefully and deliberately withheld from people unqualified by their (presumably inferior) natures from being able to deal with it.

I’m afraid that intellectuals are often prone to elevate themselves to the electi and to look down upon the mere auditores. Consider this passage, from the Gospel of John:

So the people were in two minds about him—some of them wanted to arrest him, but so far no one laid hands on him.

Then the officers returned to the Pharisees and chief priests, who said to them, “Why haven’t you brought him?”

“No man ever spoke like that!” they replied.

“Has he pulled the wool over your eyes, too?” retorted the Pharisees. “Have any of the authorities or any of the Pharisees believed in him? But this crowd, who know nothing about the Law, is damned anyway!” (7:43-49)

How does God spend his time? According to Aristotle, he spends it like a philosopher — but contemplating the only thing in the universe worthy of his attention: himself. According to some of the classical rabbis, he spends it like a rabbi, studying Torah.

What about the masses? Who cares?

It’s a dramatically undemocratic and elitist point of view, and one that is quite foreign to most Christian sensibilities and, in fairness, to mainstream Islam and probably to most Jews. The Sermon on the Mount has absolutely nothing to say about intellectual attainments or cultural sophistication. Neither Jesus nor Joseph Smith came from the academic aristocracy.

One of my absolute favorite passages from C. S. Lewis occurs in a sermon, entitled “The Weight of Glory,” that he delivered in the Church of St Mary the Virgin, Oxford, on 8 June 1942:

“It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which,if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree helping each other to one or the other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all of our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations – these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit – immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.”