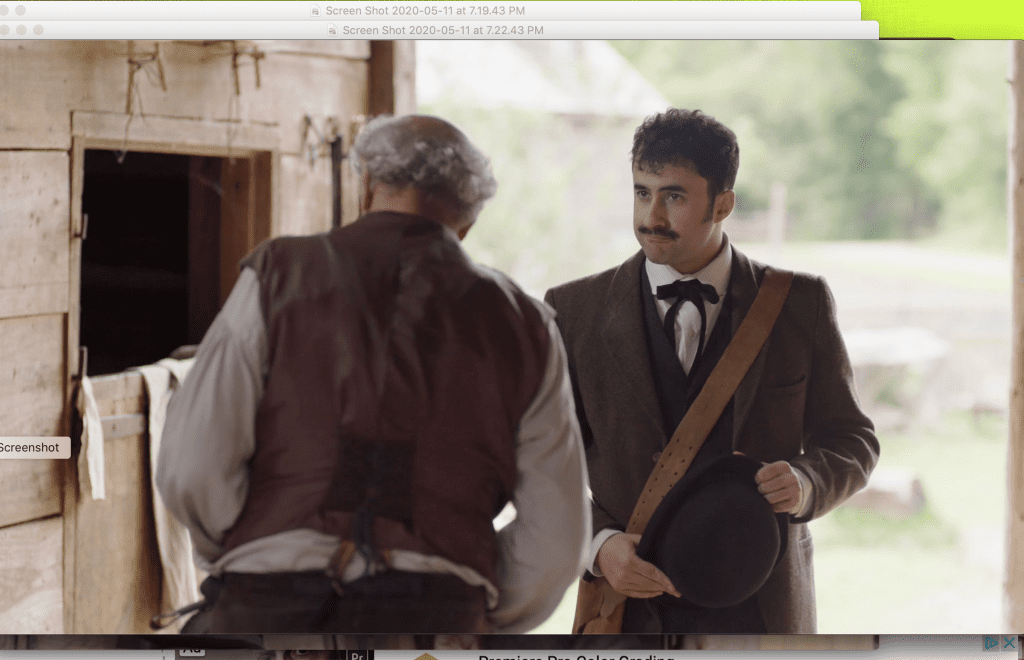

In response to my immediately previous blog entry, entitled “David Whitmer’s June 1829 journey from Fayette to Harmony and back,” I received the following comment and question: “If you zoom in on the actor’s (who is playing David Whitmer) lower back, you can clearly see an electronic device of some sort with a bundle of wires. What is this?”

Now, I wasn’t on the set for the filming of the older David Whitmer in his livery stable. So, although I was confident that I knew the answer, I wrote to both the film’s executive producer, Russell Richins, and its director, Mark Goodman, for The Authoritative Word. Here are their replies:

Russell Richins: “It is a tie, part of his vest. Any mics or mic packs that were used were hidden very well. . . . We can vouch that it is not a mic or electronic device.”

Mark Goodman: “[I]t is a part of the clothing — period accurate clothing. There is actually a built in suspender that buttons to the pants along with ties.”

This isn’t our first go-around on this topic. So, in view of that fact, it seems that I need to re-post the blog entry below. I first posted it on 29 February 2020. Perhaps the problem derives from the fact that 29 February is a day that comes around only once every four years. In any event, the claim has plainly persisted in certain circles. So we now transition to the post of nearly two and a half months ago, including the photograph of “Martin Harris’s” back immediately below:

Still photograph courtesy of Mark Goodman.

I’ve found myself thinking of the lyrics to an old Simon and Garfunkel song today. (See the title of this blog entry, taken from “The Boxer.”)

There is, in an odd corner of the Web, an odd message board that is devoted, to a really surprising degree, to anonymously criticizing me and all my works, day in and day out, month after month, year after year. This has been going on for about a decade and a half. Over the past year or two, some of the participants there have been posting blisteringly negative reviews of the Interpreter Foundation’s Witnesses film project, for which even the dramatic portion is still only in its roughcut version, still undergoing editing, and which will only be released to theaters in October 2020.

The early bird catches the worm, I suppose. It reminds me of the old joke where one academic asks another, “Have you read Rosenbloom’s new book?” “Read it?” responds the first professor. “I haven’t even reviewed it yet.”

For the past couple of days, these dedicated critics have focused their fire on a new video sampling, drawn from both the theatrical film and its accompanying documentary, that we’ve posted on the Witnesses website. Their unanimous consensus, of course, is that the movie will stink because the preliminary trailer stinks. It’s pathetic, amateurish, and so forth. Worst of all, I’m involved with it. As a prime example of our buffoonish incompetence, they point to the wireless microphone and wires hanging from the back of one of the actors, which they can clearly “see.”

But we didn’t use such wireless microphones and wires. We used boom mikes. Or, if you prefer, “boom mics.” (I really dislike that spelling, which seems to be prevalent despite my opinion of it.) What these ardent critics are seeing isn’t a wireless microphone and wire, it’s a vest that ties in the back.

I pointed this out to one of them who mustered up the courage to confront me directly (but anonymously) about the supposed wireless microphone right here on my own blog. He responded that I was entitled to “my opinion.” But, of course, it isn’t my “opinion.” We used boom mikes, not little wireless mikes mounted on the actors’ backs.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

However, this absurd little circus doesn’t just remind me of Simon and Garfunkel. It also makes me think of A Midsummer Night’s Dream III.ii.115: “Lord, what fools these mortals be!” And it reminds me of a blog entry that I originally posted back in August 2019 (accompanied by the photograph immediately above). In the early days, explorers and proto-archaeologists were often literally walking over the remains of Pre-Columbian fortifications — walls of timber and cast-up dirt that encircled abandoned cities but that had “melted” in the heavy Mesoamerican rains — without seeing them. And why did they not see them? Because they didn’t expect to see them.

Here’s what I posted last August:

“Ancient Mayan city burned in ‘act of total war,’ scientists say”

And thanks to Jason Holker for calling this article to my attention:

I’m reminded of Mormon 8:7-8:

And behold, the Lamanites have hunted my people, the Nephites, down from city to city and from place to place, even until they are no more; and great has been their fall; yea, great and marvelous is the destruction of my people, the Nephites.

And behold, it is the hand of the Lord which hath done it. And behold also, the Lamanites are at war one with another; and the whole face of this land is one continual round of murder and bloodshed; and no one knoweth the end of the war.

I’m also reminded of something that I wrote in a review of a now long and deservedly forgotten anti-Mormon book back in 1989 or 1990:

The Book of Mormon speaks of terrible wars occurring among its peoples, as Bartley correctly points out. Yet the Maya “were on the whole a peaceful people. Their ceremonial centres had no fortifications, and were for the most part located in places incapable of defence” (p. 53). Bartley here assumes a simple equation of the Maya with the peoples of the Book of Mormon which may or may not be accurate—but, more importantly, he fails to mention Sorenson’s treatment of this issue. Nor does he show the slightest awareness of the evidence now available on “the state of war that existed constantly among many Maya cities. The modern myth that the Maya were a peace-loving, gentle people who only tended their milpas and followed the stars has fallen with a thunderous crash.” Yale Mayanist Michael D. Coe puts it simply: “The Maya were obsessed with war. The Annals of the Cakciquels and the Popol Vuh speak of little but intertribal conflict among the highlanders, while the sixteen states of Yucatan were constantly battling with each other over boundaries and lineage honour. To this sanguinary record we must add the testimony of the Classic monuments and their inscriptions.” A brief glance at the volume The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art is all that is needed to show clearly that the Maya were among the most bloodthirsty people in world history.

Which, in turn, reminds me of this:

From the article:

“Modern scientists have found that the real ancient Maya were just as war-prone as Aztecs or Europeans. . . . Contrary to their reputation, the ancient Maya engaged in plenty of warfare.”

Also from the article:

“The presence of pirates of the ancient Caribbean might . . . explain the tall pyramid [at the coastal site of Vista Allegre, not far from Cancún near the point of the Yucatán Peninsula] that could serve dual functions: for religious ceremonies and as a lookout.”

Which, in turn, reminds me of the portion of the story of Gideon and King Noah recounted in Mosiah 19:5-6:

And it came to pass that he fought with the king; and when the king saw that he was about to overpower him, he fled and ran and got upon the tower which was near the temple.

And Gideon pursued after him and was about to get upon the tower to slay the king, and the king cast his eyes round about towards the land of Shemlon, and behold, the army of the Lamanites were within the borders of the land.