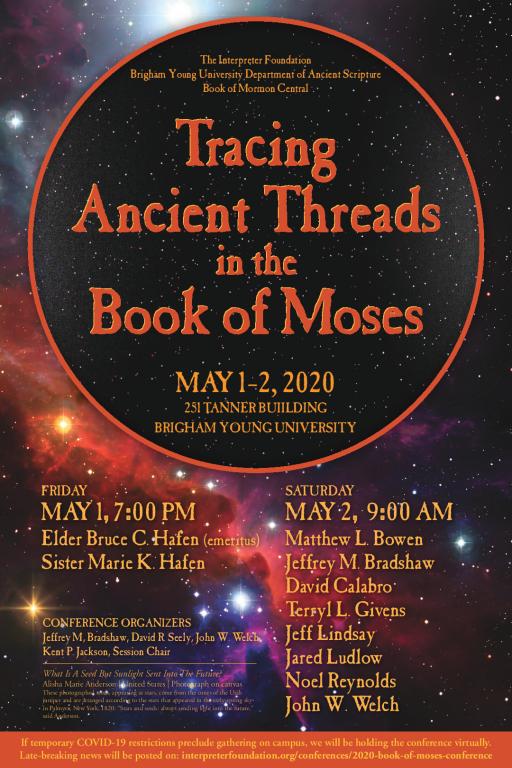

Don’t forget the Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses Conference, which begins on Friday evening, 18 September 2020, and continues on Saturday, 19 September 2020. You can watch it at no charge.

In honor of the conference, I share again a column that I first published in the Deseret News on 30 January 2014:

The scripture John 11:35 (“Jesus wept”) is well known as the shortest verse in the King James Bible. It’s less known, however, as one of the Bible’s most significant passages. But it is precisely that.

Why? Because it demonstrates the Savior’s personal care for humanity and shows him, though divine, to be emotionally involved with us.

But, in that regard, Moses 7:28-29 in the Pearl of Great Price is even more remarkable:

“And it came to pass that the God of heaven looked upon the residue of the people, and he wept; and Enoch bore record of it, saying: How is it that the heavens weep, and shed forth their tears as the rain upon the mountains? And Enoch said unto the Lord: How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity?”

How is it possible for God to weep? For centuries, classical Jewish, Christian and Islamic theologians have agreed that it isn’t. Such behavior would be unworthy of him. God’s emotions seem, it’s true, to be on display throughout the scriptures, but the passages describing them have typically been dismissed as metaphorical, as symbolic of something else.

Recent biblical scholarship, however, is reconsidering the emotions of God. The sections of the book of Jeremiah that precede the Babylonian captivity, to choose from among many possible examples, are absolutely replete with images and divine statements that depict God as deeply caring, worried even, about the punishment that he himself has to impose upon his people.

In Jeremiah 12:7-8, for instance, the Lord is represented as saying, “I have given the dearly beloved of my soul into the hands of her enemies.”

These words remind us of the internal conflict within the soul of a father who loves his children, but who must still punish them and to not intervene when consequences occur. The God speaking here is no distant, uninvolved, unemotional monarch. He loves Israel.

But even while biblical scholars increasingly recognize God’s “passions” as genuinely scriptural, doing so is deeply problematic in the view of many traditional systematic theologians.

For how is it possible to have emotions without a body? Emotions are inseparably connected with such things as tears, rapid heartbeat, “feelings.” Pure mind, if such a thing exists, would seem incapable of anything remotely recognizable as emotion. If, these theologians argue, God has emotions, it must follow that he has some sort of body. But he cannot have a body. Thus, he can have no emotions. Which means not only that he can’t be angry with us but that he can’t love us in any human-like sense of the word, or care for us, or feel our pain, or mourn our poor choices.

Like Enoch, theological commentators have been astonished at the sheer notion that God might weep. Unlike Enoch, though, who was an eyewitness, they flatly reject it. Classical theology has historically tended to depict God as a distant, dispassionate and literally apathetic being unmoved by emotion. The unmoved mover doesn’t weep. He (or, perhaps better, it) moves, but is not moved. Nothing can have any impact on him.

If emotional displays such as tears require a body, classical theism’s solution is to deny all the emotions mentioned for God in the Bible, just as it denies or reinterprets the many passages that seem to describe him as having bodily form. (The embodied Jesus of John 11:35 can be permitted emotions precisely because he assumed flesh and human nature; it’s far less acceptable to grant such “feelings” to his Heavenly Father or to God before the Incarnation.)

The question is whether Christians will in the final analysis opt for their traditional theology, or for the Bible. The two are difficult if not impossible to reconcile.

The Pearl of Great Price’s account of Enoch offers a spectacular instance of a suffering and weeping God, far clearer, even, than anything in the Bible. Fortunately, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are entirely comfortable with an embodied deity.

For those who accept the scriptures of the Restoration, Heavenly Father is not only a being with emotions, but a God who, because he is perfect and perfectly embodied, feels more deeply than we can even begin to imagine. “God is love,” says 1 John 4:8. He not only has and enjoys an emotional life, but the most perfect emotional life possible. His love is richer, deeper, than any love we can imagine. Therefore, he feels both pain and sorrow for his children, and boundless love and joy for them.