(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Some readers will already have noticed a number of similarities between the Qur’an and the standard works of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And, indeed, there are many. The present section will highlight some of them. In this regard, perhaps the most obvious feature of the Qur’an is the fact that it contains many of the same stories and refers to many of the same historical figures that are familiar to the West from the pages of the Bible.

The Qur’an speaks, for instance, about the fall of Lucifer and the temptation and fall of Adam and Eve.[1] It is familiar with the story of Adam’s naming of the animals and the conflict between Cain and Abel.[2] The story of Noah appears more than once.[3] Job is mentioned, as is a figure called Idris, who is universally identified by Muslim commentators with Enoch.[4] Even Jonah is mentioned.[5]

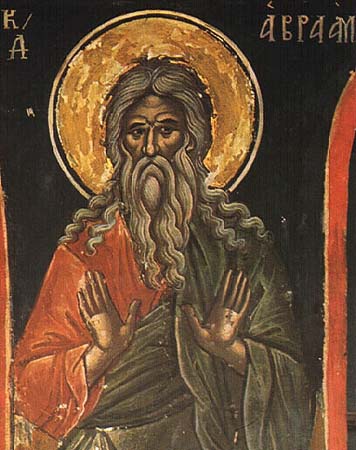

Told often, and in considerable detail, are the stories of Abraham and his nephew Lot, including the miraculous annunciation of Isaac, Abraham’s near-sacrifice of his son, and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.[6] The story of Abraham’s youthful renunciation of his idolatrous family and people is favored and referred to numerous times throughout the Qur’an.[7] The Qur’anic retelling of the story, however, contains a number of interesting details that either do not occur in the Bible or are not emphasized at all. Abraham appears in the Qur’an as a watcher of the skies, much as he does in the third chapter of the Book of Abraham. And the prayer for wisdom and righteousness that the Qur’anic Abraham offers seems to parallel his quest as recorded in Abraham 1:2. Some details are even amusing, as in the following dialogue between the patriarch and an unidentified royal idol worshiper:

Have you not heard of him who argued with Abraham about his Lord because He had bestowed upon him the Kingdom?

Abraham said: “My Lord is He who has power to give life and to cause death.”

“I, too,” replied the other, “have power to give life and to cause death.”

“God brings up the sun from the east,” said Abraham. “Bring it up yourself from the west.”[8]

A personal favorite of mine, however, is a story to which the Qur’an merely alludes, without telling it all in detail.[9] This is the story of Abraham and the idols of his father, with which some Latter-day Saint readers will already be familiar, from the book called Jasher:

Attempting to demonstrate to his father Terah the futility of worshiping idols, Abraham one day went into his father’s shrine with a hatchet and hacked all of the gods to pieces—except for their chief. Then, before leaving the room, he placed the hatchet in the hands of the still-intact chief god. His father, hearing the noise of violent chopping in his private sanctuary, ran and met Abraham at the door. Pushing past his son, Terah went into the shrine. There he found all the idols fallen down and broken, while the chief idol still stood with the hatchet in its hand. He was furious. Knowing his son’s attitude toward idolatry and having seen his son emerging from the shrine, he naturally demanded to know what Abraham had done to the gods of his father. But Abraham denied having anything to do with the destruction of the idols. “No,” he said, “it was the chief god who did it, out of jealousy when the other, subordinate gods had tried to beat him to the meat offering.” Terah roared with anger. “You are lying!” he told his son. “These gods are just wood and stone. I made them myself!” How could they possibly have done anything like what Abraham had described? “Ah,” said Abraham, “but that is precisely the point! They are merely wood and stone, which can neither hear nor speak nor act. So why pray to them?”[10]

I have already spoken about the common assumption that the Qur’an identifies the son of Abraham who was nearly sacrificed upon Mount Moriah as Ishmael, rather than the Bible account’s Isaac. We have seen, though, that the Qur’an nowhere names the son who came so near to human sacrifice. And, in fact, the Qur’an has a great respect for Isaac. Of Abraham, the God of the Qur’an says, “We gave him Isaac and Jacob and bestowed on his descendants prophethood and the Scriptures.”[11] Clearly, this passage teaches the continuation of the prophetic gift in the Jewish line, through Jacob or Israel. Ishmael appears in the Qur’an and is treated with immense respect as a chosen servant of God and a messenger, but Isaac is described as a prophet.[12]

[1] 2:30_39; 7:11-25; 15:26-44; 17:61-65; 20:115-23; 38:71-85.

[2] 2:31-33; 5:27-31.

[3] As at 10:71-73; 11:25-49.

[4] 21:83-84; 19:56-57, with perhaps a hint of his translation. Idris is pronounced with a hissing “s,” as Ih-DREES.

[5] 37:139-49; 68:48-50.

[6] 11:69-83; 17:50-77; 27:54-58; 29:28-35; 37:99-111, 113-38; 51:24-37; 54:33-40.

[7] For instance, at 6:74-79; 19:41-50; 21:51-72; 26:70-102; 37:83-98.

[8] 2:258.

[9]. This is the usual Qur’anic approach. It frequently refers to stories that it presumes its audience will already find familiar. This somewhat elliptical or allusive quality of the Qu’ran is probably the main reason that many Western readers find the book so off-putting.

[10] This story is told at Jasher 11:16-51. See The Book of Jasher (Thousand Oaks, CA: Artisan Sales, 1990), 25-27. This translation of the Book of Jasher first appeared in 1840. It was reprinted, at Salt Lake City, in 1887.

[11] 29:27; compare 4:54.

[12] 19:54-55; 37:112.