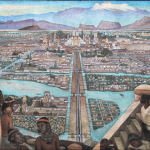

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Classical Arabic Civilization

The late Marshall G. S. Hodgson, one of the greatest Western students of Islam of the past century, developed an outline of Islamic history that I find very helpful.[1] In it, he distinguishes seven different periods. Let me summarize them here.

First, Hodgson states, there was the “Pre-Islamic Period.” It isn’t hard to understand what this is about, since it simply refers to the years from earliest time up to about 570 A.D., when the Prophet Muhammad was born. The next interval, which he calls the “Formative Period,” extends from Muhammad’s birth up to 692 A.D.[2] Among other things, this is the time in which the most important document of Islam, the Qur’an, was revealed and recorded, and the time in which the Prophet himself and his first four successors (the “rightly guided caliphs”) established powerful examples of what it means to live as a Muslim. We have already discussed important items from the Formative Period. Hodgson labels the next distinct phase of Islamic history the “High Caliphal Period.” I will discuss it in more detail below but, briefly, it was during this period that the Arab or Islamic empire attained its greatest power and prosperity. Things fell apart by 945 A.D., and the Muslims entered what Hodgson terms the “Middle Periods” of their history, which lasted until 1500. (Hodgson divides this era in two. He distinguishes the “Early Middle Period” from the “Later Middle Period.”) When gunpowder and other modern technologies made it possible for certain innovative states to swallow up those around them, the Muslims entered a period of partial recentralization. This Hodgson terms the age of the “Gunpowder Empires.” Finally, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Western imperialism entered the Islamic world—first in the person of Napoleon. With this, the Muslims moved into the Modern Period.

The High Caliphal Period

By the end of the seventh century, although institutions continued to be formed, the basic structures of Islamic belief and practice were pretty much in place. The Arabs who had poured out of the Arabian peninsula and launched their astonishing series of conquests had left the old local bureaucracies in control of day-to-day governance. The conquerors were uninterested in such lowly matters and probably had no competence anyway, since, as we have seen, the Arabian Peninsula really had no traditions of government in any recognizable sense. Thus, native Christians in one part of the new empire and Mazdaeans or Zoroastrians in the other continued to administer daily affairs in languages like Aramaic and Persian, just as they had in the years before the conquest.

Finally, in the late seventh century, Arabic was made the language of administration. This had notable consequences. Fluency in Arabic now became the passport to social advancement and prestige. People who wanted to get ahead in the new order had to learn it. This was relatively easy for speakers of Aramaic to do, since, as a Semitic language like Hebrew, it was closely related to Arabic. (The situation was similar to that of a speaker of Spanish having to learn Portuguese.) It is probably for this reason that Aramaic essentially died out. It was simply absorbed into the dominant language. Persian, on the other hand, is a language utterly unrelated to Arabic.[3] This made the speech of the conquerors perhaps more difficult for native Persian-speakers to learn, but it also led to a clear distinction between the native language and the learned second language that prevented Persian from assimilating to Arabic and simply vanishing or going extinct as Aramaic did. Thus, while Persian disappeared for a number of centuries from public or official use, it continued to be spoken at home. This is shown clearly by its reappearance in literary form around the year 1000 A.D. (Since then, of course, it has had a continuous history. Today, Persian is the language of the Islamic Republic of Iran.)

[1] In his stunningly brilliant three-volume work The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1974).

[2] Hodgson has his reasons for choosing precisely this year as his cut-off date for the Formative Period, but they are beyond the scope of this book.

[3] I will refer throughout this book to Persian, rather than speaking of the language by its own native title, Farsi. It has become fashionable in some circles to talk of Farsi when speaking English, and some will no doubt be puzzled by my refusal to do so. But there is a simple reason for it: We do not usually talk in English about Deutsch or Francais or Español or al-‘Arabiyya. I see no point in making an exception for Persian.