(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

But the emphasis of the ‘ulama’ on law and on behavior came, in the eyes of some highly committed Muslims, to seem a mere concentration on the externals, on the letter and not the spirit of Islam. They yearned for a more personal and warm relationship with God than plain obedience to a law code could possibly supply on its own. Among these pious Muslims were the Sufis, the Islamic mystics, who were more concerned with contemplative or introspective spirituality. (Their name comes from the simple woolen clothing they preferred.)[1] The Sufis prevented Islam from becoming a cold religion of heartless external observance, and they gave to the Muslims and to the world in general some of the finest religious literature produced anywhere.

The worldly culture of the court and the “polite classes,” by contrast, proceeded without much real reference to the ‘ulama’. The courtiers and the administrators of the empire gave honor to the ‘ulama’—often, no doubt, sincerely—but generally followed lifestyles of which the ‘ulama’ did not approve. Etiquette, conversation, clothing, fine arts, literature, poetry, music—these were the concerns of the political and social elite. Manuals were actually published for the benefit of the courtiers and the scribes that listed in concise form the basic information that a cultivated man ought to know. (It was a kind of intellectual “Dress for Success” technique, with scraps of literature, history, geography and biology—especially of the “Believe It or Not” variety. The emphasis was on anecdotes and curiosities, to enable the would-be social climber to sparkle in polite, urbane conversation.)

The high point of the Abbasid caliphate and of the empire over which the caliph presided probably came during the splendid and luxurious reign of Harun al-Rashid.[2] Ruling from the great city of Baghdad around the year 800 A.D., Harun was a contemporary of Charlemagne. But his empire was incomparably more magnificent than Charlemagne’s, excelling it as far as Baghdad excelled Aachen, Charlemagne’s capital. Harun was a great patron of culture. Poets, musicians, jurists, historians, scientists, architects, creative minds and hands of all types found support from him. His reign is recalled so fondly in Arab tradition that he even finds a prominent place in the tales of the Thousand and One Nights. In those stories, he is depicted wandering around Baghdad in disguise, with his prime minister at his side, to see what his city and its residents were really up to. He gets into many adventures, and has many a narrow escape, but he emerges from it all as a kindly and good-natured man, sincerely interested in the welfare of his subjects. (However, these stories of the disguised and wandering ruler seem to have been directly inspired by an eleventh-century Egyptian ruler, al-Hakim bi Amr Allah of the Fatimid dynasty, rather than by the historical Harun al-Rashid. Harun’s name somehow became attached to the figure, and the scene of the action was somehow transferred from Cairo to Baghdad.) It was a time of peace and great prosperity; a check could be written in Egypt and drawn on a bank in Iraq (which may occasionally be more difficult nowadays than it was then.) The government’s policy was what we might today call laissez faire or the free market. This may have been one of the secrets of the era’s wealth. The purpose of the state was little more than to maintain law courts, to defend the frontiers, and to preserve the citizens’ security in the streets and on the roads of the empire. Government inspectors saw to it that weights and measures were honest and that the coinage was sound; otherwise, commerce was free and, on the whole, unregulated. The wealthy members of society, including the caliph, gave generously to charities in their capacities as private people.

By the time that the ninth century was well underway, however, the caliph’s office had grown much weaker. There were several reasons for this. First, the caliphs had begun to rely upon imported soldiery. The old military fire had gone out of the Arabians—those who had actually come from the Arabian Peninsula, or whose ancestors had done so. They were rich, comfortable, and had little enthusiasm for toilsome and risky adventures. How, after all, could they possibly be more comfortable than they already were? Why look for more? And there was a good chance that military service might cost them more than mere comfort.

So the caliphs began to import young barbarian slaves, mostly Turks from central Asia, who had never known the soft life. But these soldiers, barbarians though they might be, were not at all stupid. They soon realized, much as the Roman Praetorian guard had, centuries before them, that, if they were in total control of the ruler’s safety, they could also control the ruler himself. And if they controlled him, they knew, they would profit immensely. Indeed, after 860 A.D. they actually named the caliph, preferring to choose weak men whom they could control in their own interests. Needless to say, both the institution of the caliphate and the empire itself suffered. To make matters worse, the center of the empire was growing weak, while the extremities were strong.

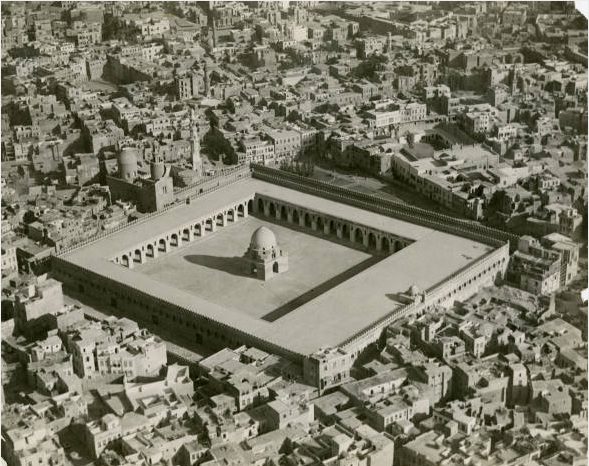

A kind of political centrifugal force began to pull the empire apart. Strong military governors in outlying areas became de facto independent, while still formally declaring their loyalty to Baghdad. They had long since lost their enthusiasm for sending the tax revenues of their provinces to Baghdad; they wanted the money to stay at home, to do good—or to do mischief—in their own lands. They were far away, communications were poor, and it would have been difficult for the caliph to impose his will on them at the best of times, when the caliphate was robust. But it was not robust. And, to take one example, when the provincial governor of Egypt, Ibn Tulun (d. 884), wrote to the caliph asking that his son be recognized as his successor, there was little the caliph could do. He knew, of course, that approving father-son succession was tantamount to blessing the rise of a new and more or less independent dynasty, but he also knew that, if he said “no,” he would be ignored and there would be a dynasty anyway. So both sides decided to maintain the myth of loyalty to Baghdad. The new dynasty received a certain kind of legitimacy from the transaction, while the caliph managed to save face and to receive, if everything went well, some token tax revenues from the provinces. But these were not enough, and the caliph’s finances deteriorated even further. To complicate things, the vastly important irrigation canals of Mesopotamia had begun to silt up and to deteriorate, and the central authorities lacked the funds to repair them. Finally, it became clear that Baghdad was, for all intents and purposes, bankrupt.

[1] The Arabic word suf means “wool.” It is pronounced “soof,” and the individual mystic is a “SOO-fee.”

[2] Pronounced “Hah-ROON ar–Rah–SHEED,” the name or title of this ruler is Arabic for “Aaron the Rightly-Guided.”