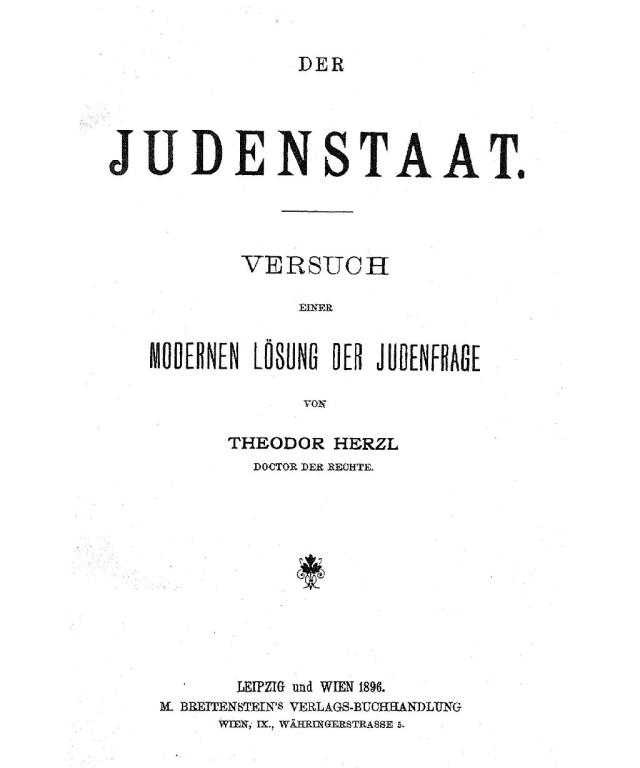

This book, in many ways, marks the beginning of the Zionist movement. (Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

In 1882, young Jews calling themselves “Lovers of Zion” began actively to promote immigration to Palestine among their people. This was the beginning of what came to be known as “practical Zionism,” which advocated building Jewish settlements in Palestine. (It was “practical” in the sense that it pushed for real action to implement the dream Jews had been dreaming for nearly two millennia.) Jews returning to Palestine in the late 1800s and early 1900s began the heavy work of draining swamps, digging wells, replanting forests, and reclaiming arid land for cultivation through the establishment of irrigation systems. Farm settlements, following various patterns of cooperative organization, began to appear throughout Palestine. These were an important part of Zionist colonization, since many of the Zionists were influenced by the socialist ideals and theories that were widespread among “progressive” European thinkers at the time.

“Political Zionism,” which went beyond merely calling for Jewish settlement in Palestine and sought the establishment of a Jewish state, was largely the creation of an Austrian journalist by the name of Theodor Herzl. Obviously, Theodor Herzl wasn’t the first Zionist, the first to dream of a Jewish return to Palestine, but he gave that dream life.

Born in 1860 in Hungary, in what is today eastern Budapest, Herzl grew up in a secular, German-speaking Jewish family. He was, in fact, a passionate lover of German culture, and his youthful hope was that, through education, Hungarian Jews like himself could shed what he regarded as their “shameful” Jewish characteristics, acquired over centuries of poverty, humiliation and persecution, and become fully European.

In his late teens, his family moved to Vienna, where he studied law at the university and even joined a German nationalist fraternity. After a brief legal career, he became a successful Paris-based journalist and a moderately successful playwright. He didn’t write about Jewish topics.

However, although some biographers dispute this, according to Herzl himself it was in Paris that the focus of his life changed. The notorious “Dreyfus affair,” in which the French Jewish army officer Albert Dreyfus — falsely accused of treason and of spying for Germany — was framed, convicted and imprisoned on Devil’s Island, convulsed France from 1894 until 1906. His Jewishness was a central factor in the case. Prominent figures such as the great stage actress Sarah Bernhardt, the poet Anatole France, and the mathematician Henri Poincare denounced the blatant anti-Semitism of the case. Most spectacularly, the vocal outrage of the great novelist Emile Zola led him to write a now famous open letter, J’accuse—”I accuse”—that brought the government’s wrath down upon him and forced him into hasty English exile. But it also helped to win Captain Dreyfus a new trial and, eventually, acquittal.

But Theodor Herzl later recalled mobs outside his hotel during the trial, chanting “Death to the Jews!” Himself a nonreligious Jew, he was shocked to the core. If anti-Semitism, prejudice against the Jews, could become so powerful in a modern, enlightened country like France, it seemed to him that things could only be worse elsewhere. The hope of many Jews to fit in, to assimilate and be accepted as Frenchmen and Germans and Englishmen just like anyone else, now appeared to Herzl to be an illusion. If, after nearly two thousand years of Christianity, it had not yet happened, there was good reason to believe that it never would. Concluding that anti-Semitism would never go away, that it could only be fled, and that, therefore, an independent Jewish state was urgently necessary, he embraced Zionism and his own Jewish identity.

The only possible solution, in Herzl’s view, was for Jews to create an independent Jewish state, in which they would not need to depend on the fickle goodwill of Christians. He decided to devote the rest of his life to that cause. It was Herzl, essentially, who put the international Zionist movement in motion. He worked tirelessly, appealing to Jewish leaders and the rulers of many nations, writing, speaking, and traveling indefatigably.

In 1896, he published a short but pivotal book entitled Der Judenstaat (“The Jewish State”) as a kind of charter for political Zionism, bearing the subtitle Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage (“Proposal for a Modern Solution to the Jewish Question”). In it, he contended that Jews should leave Europe for Argentina or, even better, for their historic homeland in Palestine. There, free from bigots, they would be able to practice their religion and express their culture without oppression. (Late in life, Herzl also considered the east African territory of Uganda as a possible Jewish homeland.).

Enormously influential from the start, his book was also controversial. In fact, it still is, even among some Jews. Many secular Jews, for example, feared that Zionism endangered their efforts to integrate into European society, to be accepted and assimilated. (They didn’t see Hitler coming.) They feared, in fact, that it might make things worse. If Jews themselves were claiming that they were not really Germans, or not true Frenchmen, but had primary loyalty to another, foreign nation, how could they possibly complain when German and French anti-Semites accused them of precisely that? Many religious Jews saw in it an attempt to usurp the role of God and the Messiah. They rejected political Zionism on the belief that only God could or should restore the Jews to their ancient homeland.

To Herzl, though, Zionism was the Jews’ only realistic hope.

“The Jewish question,” he wrote, “persists wherever Jews live in appreciable numbers. Wherever it does not exist, it is brought in together with Jewish immigrants. We are naturally drawn into those places where we are not persecuted, and our appearance there gives rise to persecution. This is the case, and will inevitably be so, everywhere, even in highly civilised countries.”

“We have sincerely tried everywhere to merge with the national communities in which we live,” he said, “seeking only to preserve the faith of our fathers. It is not permitted us. In vain are we loyal patriots, sometimes superloyal; in vain do we make the same sacrifices of life and property as our fellow citizens; in vain do we strive to enhance the fame of our native lands in the arts and sciences, or her wealth by trade and commerce. In our native lands where we have lived for centuries we are still decried as aliens.”

Shortly thereafter, an international gathering of Zionists was planned for Munich, but Jewish opposition prevented that. So the First Zionist Congress was held in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897. It was a milestone; the movement that would eventually culminate in the establishment of the state of Israel was now well underway.

Although the Basel gathering elected him president, Herzl never saw his dream realized. He died of heart disease in 1904, shortly after his 44th birthday, and was buried in Vienna. “I wish to be buried in the vault beside my father,” he declared in his will, “and to lie there till the Jewish people shall take my remains to Israel.” In many respects, his short life must have seemed a failure. His widow died only three years after him. She was cremated and her ashes were misplaced. Of the three children produced by their unhappy marriage, one died of a heroin overdose, another by suicide, and the third was executed in the Nazi death camp at Theresienstadt. In 1946, his only grandchild jumped to his death from Washington, D.C.’s Massachusetts Avenue Bridge.

In 1949, though, a year after Israel’s founding, Theodor Herzl’s remains were moved from Austria to Jerusalem’s Mount Herzl, which had been named in his honor.