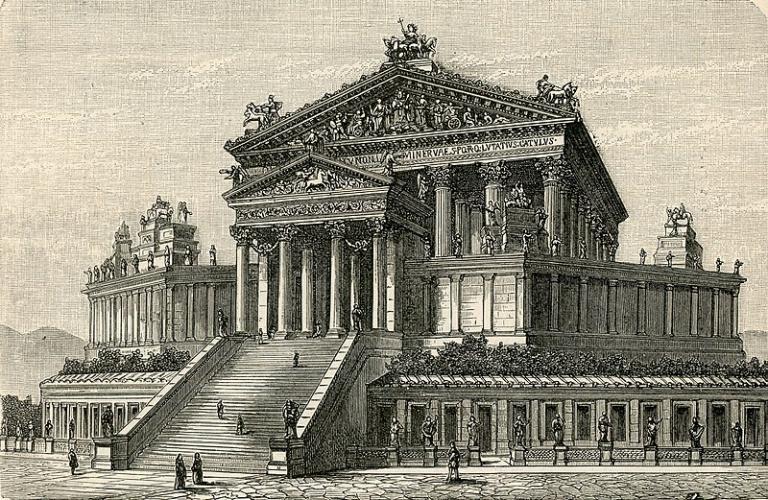

An artist’s reconstruction of the ancient Roman temple of Capitoline Jupiter

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I’ve been writing regular newspaper columns for the Deseret News for roughly eleven years. Over several of those years, I was writing three columns every two weeks — a weekly solo column, called “Defending the Faith,” on Latter-day Saint issues, and a biweekly column (co-authored, until his shocking and too-early death at the end of 2019, with my friend Bill Hamblin) on world religions. (Links to most of the former, though not quite all, are gathered here. Links to most if not all of the latter are gathered here.)

Well, that’s all come to an end.

After a month of uncertainty occasioned by the transition of the Deseret News away from a principally printed format to an electronic one — a reflection of the turbulence and change happening in the world of print journalism more generally — I received word last night that my bi-weekly column on world religions no longer fits the design of the newspaper, meaning that my tenure as a columnist for the Deseret News is now finished. The “Mormon Times” section disappeared quite a while ago, and now the “Faith” section is gone. My LDS-oriented column had already been terminated somewhat more than a year ago, and now I’m done with the bi-weekly column on religions of the world.

I won’t deny that I’m saddened and disappointed by this development. The columns had come to be a fixture in my world. Part of my regular routine.

I’m still trying to decide what I’m going to do instead, how I’m going to use the time that regularly went to the Deseret News.

Here, in the meantime, is the last column that I submitted to the editor of the Deseret News. It was never published. As you will easily see, it was written before the inauguration of President Joe Biden; it was submitted on 8 January. Perhaps, though, you’ll still find it of some interest:

The United States Capitol, often simply called the “Capitol Building,” is much in the news these days. On 6 January, it was breached by a mob, the first time it had been actually invaded since the British partially burned it in 1814 (during the somewhat misleadingly named “War of 1812”). On Wednesday, 20 January, it will be the location of the 59th presidential inauguration in American history.

The Capitol is, of course, the seat of the national legislature of the United States of America—the first of the three branches of the federal government mentioned in the Constitution and thus, literally, the first among equals. In imitation of it, state legislatures from Alaska to Florida and from Hawaii to Maine also meet in buildings called “capitols”—many of them (including Utah’s) architecturally patterned after it.

But why is it called the “Capitol”?

Curiously, nobody really knows for sure, except that Thomas Jefferson was involved in it.

Generations of American elementary school students have puzzled over the difference between “capital,” as in “capital city,” and “capitol,” referring to the prominent building that sits in that capital city. But, although they’re ultimately related, the two words are quite distinct in their origins as well as in their spellings.

The word “capital” derives from the Latin “caput,” meaning “head.” Perhaps that fact will be a little bit easier to believe if we note that the genitive or possessive form of “caput” is spelled “capitis.”

The word “capitol,” by contrast, comes from the “Mons Capitolinus” or “Capitoline Hill,” the most important of the famous “Seven Hills” of ancient Rome, which divided the Roman Forum from the “Campus Martius” or “Field of Mars.”

In 1793, while he was serving as Secretary of State under President George Washington, Thomas Jefferson gave the name “Capitol Hill” to the area where federal legislators meet today, and, somehow, he made it stick. Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the French-American engineer who developed the overall layout for the new national capital, had known the area as “Jenkins Hill” or “Jenkins Heights.”

Because of its slight prominence in a mostly flat area, the 1791 “L’Enfant Plan” had marked Jenkins Hill as the future location for what it called “Congress House.” It was, L’Enfant said of the hill, a “pedestal waiting for a monument.”

Reviewing the city design, though, Jefferson insisted that Jenkins Heights be termed “Capitol Hill,” instead. And “Congress House” was to be the “Capitol.”

Why Jefferson wanted these names is not at all obvious. Perhaps it reflects a confluence of his classical education and his grand dreams for the country that he and the other Founders were inventing. But the source for “Capitol” as the name of a building is reasonably clear:

Ancient Rome’s Capitoline Hill had originally been sacred to the god Saturn, who was linked with time, the agricultural cycle, wealth, and plenty. Accordingly, it had borne the name “Mons Saturnius.” But then, late in the sixth century before Christ, a temple was built atop the hill to Jupiter, Saturn’s eldest son and the king of the classical Roman gods. Called the “Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus” (meaning “Temple of Jupiter, the Best and the Greatest”), it was the largest of the ancient temples in the city and the most important of them. It may be for that reason that it began to be known as “Capitolium,” which, like “capital,” comes from “caput,” the Latin word for “head.” Eventually, because of its splendor and significance, the entire hill on which it stood took on its name.

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on Capitoline Hill never served as an official place of government or political debate or legislation; the Roman Senate met in the Curia Julia over in the Forum. Nevertheless, it is from that ancient pagan sanctuary that, at the slightly puzzling insistence of Thomas Jefferson, Washington DC’s “Capitol Hill” and the seat of the national legislature of the United States take their names.

Today, in the same way that such geographical descriptors and building names as “Vatican,” “the Kremlin,” “Whitehall,” “Downing Street,” “the White House,” “London,” “Moscow,” and “Washington” itself are used as metonyms or rhetorical substitutes for the governments of Russia, Great Britain, the United States, and so forth, “Capitol Hill”—originally the location of the foremost Roman temple to Jupiter, “djous-pater,” the “sky father”—has become a common stand-in for the actions and deliberations of the legislative branch of the United States federal government.