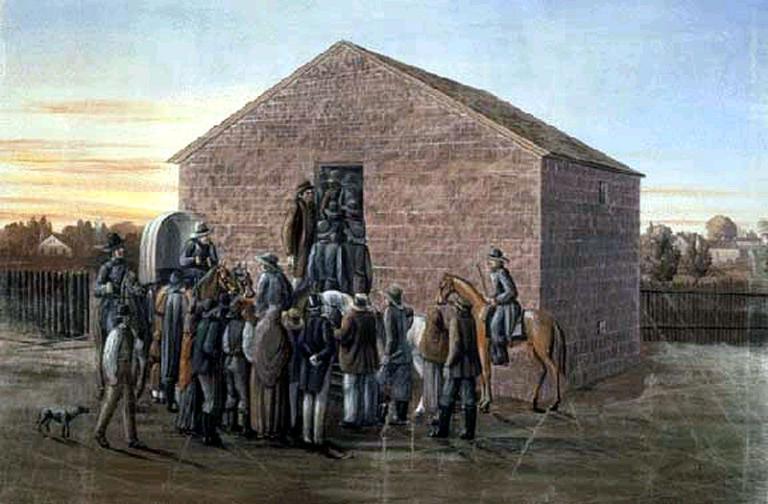

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

***

The big Deseret Book and Excel Entertainment event for the Witnesses film is tomorrow (Thursday) night, 14 October 2021. Don’t miss it. We’ll be reading a list of persons from the lectern who have been called on missions to the new Antarctica McMurdo Station Mission. Your name may be on it.

For further information, see here. To RSVP, see here. For a brief recent television interview related to the film and the event, see here.

***

Since I last mentioned any such thing, these new items have appeared on the entirely moribund website of the Interpreter Foundation:

Estimating the Evidence Episode Episode 15: On Trajectories of Truth

This is the latest installment — the fifteenth of a projected twenty-three — in Kyler Rasmussen’s series of Bayesian explorations into the truth-claims of the Book of Mormon.

During 1978, 1979, and 1980, Hugh Nibley taught a Doctrine and Covenants Sunday School class. Cassette recordings were made of these classes and some have survived and were recently digitized by Steve Whitlock. Most of the tapes were in pretty bad condition. The original recordings usually don’t stop or start at the beginning of the class and there is some background noise. Volumes vary, probably depending upon where the recorder was placed in the room. Many are very low volume but in most cases it’s possible to understand the words. In a couple of cases the ends of one class were put on some space left over from a different class. Even with these flaws and missing classes, we believe these these will be interesting to listen to and valuable to your Come, Follow Me study program.

The Interpreter Radio Roundtable for Come, Follow Me Doctrine and Covenants Lesson 43, “O God, Where Art Thou?” on D&C 121-123, featured Terry Hutchinson, John Gee, and Kevin Christensen. This roundtable was extracted from the 12 September 2021 broadcast of the Interpreter Radio Show. The complete show is available at https://interpreterfoundation.org/interpreter-radio-show-September-12-2021/. The Interpreter Radio Show can be heard Sunday evenings from 7 to 9 PM (MDT), on K-TALK, AM 1640, or you can listen live on the Internet at ktalkmedia.com.

***

I can scarcely express how much I’m looking forward to this:

“The Most Reluctant Convert: The Untold Story of C. S. Lewis”

My wife and I already have our tickets.

***

I’m reading Alexander L. Baugh, Steven C. Harper, Brent M. Rogers, and Benjamin C. Pykles, eds., Joseph Smith and His First Vision: Context Place, and Meaning (Provo and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2021). Here, I will share notes from one of the essays that I’ve read in it, Richard E. Bennett’s “Quiet Revivalism: New Light on the Burned-Over District,” 89-108:

Joseph Smith-History 1:5 reports Joseph’s experience of “an unusual excitement on the subject of religion” that surrounded him and led him into the woods for guidance. Many have jumped from an “unusual excitement” about religion to the idea of mass revivals and then on to boisterous camp meetings. Critics of the Restoration, seeking to discredit Joseph, have claimed that no such revivals were occurring there at that time, which would make him a liar. But it’s not clear that no such revivals occurred. And, anyway, it’s not at all obvious that they’re needed. After all, Joseph doesn’t mention revivals or camp meetings in his canonized account. And Professor Bennett seems to be entering into that fray with his suggestion that “revivals” needn’t involve mass camp meetings.

These “reviving and converting influences of the Holy Spirit,” this “season of refreshing from on high,” reached Palmyra not only via the sounds and and excitements of outdoor camp meetings. These influences also owed much, if not everything, to dedicated missionaries and ministers who called upon friends and family in the sanctity of their own cabin homes by the fire and the hearth to seek the Lord through mighty private prayer for forgiveness and salvation. Besides this, there was the personal outreach of female missionaries and visiting teachers — a very intimate, deeply personalized revival of faith and a face-to-face invitation to repent and come unto Christ, which I am terming quite revivalism. (90, italics in original).

It is important to understand what the term revival meant at that time to these men of the cloth. While it is true that later Presbyterian divines such as Charles Finney turned to outdoor camp meetings as the means of grace, most Old and New School Presbyterian pastors preferred a much different path to personal conversion, a form of quiet revivalism that extended into the parlor of most Palmyra homes. (95)

Thanks to the pioneering research efforts of the late Milton V. Backman, we know that these Presbyterian-flavored revivals bore particular fruit in 1819 and 1820, “more numerous, extensive and blessed” than in any previous years and greater than in any other state. Presbyterianism grew in New York State by 35% in 1820 with 1,513 of the 2,250 new converts coming from the burned-over district. (100-101)

The local Palmyra Register wrote in the spring of 1820 of his [Rev. Asahel Nettleton’s] recent successes and of the “religious excitement” of the times in the communities east of Palmyra. His style of Presbyterian preaching, his house-to-house visits, and his caring concern paint a very different picture from that of the loud Methodist-dominated camp meeting. The former was as still as the latter was boisterous and may beg a revision to what some readers assume was the dominant spirit of revivalism. (102)

And it was among the youth — both young men and young women — that revivals of all kinds bore the greatest fruit and where conversion most often occurred in private, in the stillness and quiet created by seeking for answers to probing, personal prayers. Indeed, as one scholar has concluded, “The most striking and consistent characteristic of the Second Great Awakening was the youthfulness of its participants.” One Baptist minister writing in January 1820 about mass conversions in Cornish, New York, told of “a number of young children: from “thirteen down to seven years of age” singing hosannas to the Son of David. (102)

It was common for ministers of all faiths to report from the field that “two thirds of [the] whole number of converts [were] under 20 years of age.” (103)

From this and scores of other similar descriptions, it is clear that while the answer to Joseph Smith Jr.’s teenage prayers would eventuate in the birth of a new world religion, his “determination to ask of God” on “the morning of a beautiful, clear day” and the way he went about approaching heaven that spring of 1820 were entirely consistent with the contemporary upstate New York culture of Presbyterian-led revivalism — a time known for its deeply personal, very quiet private pleadings to heaven, when young women and young men, with scriptures in hand or at least in mind, entered their own sacred groves to pray for the salvation of their souls (Joseph Smith–History 1:14). (104)