***

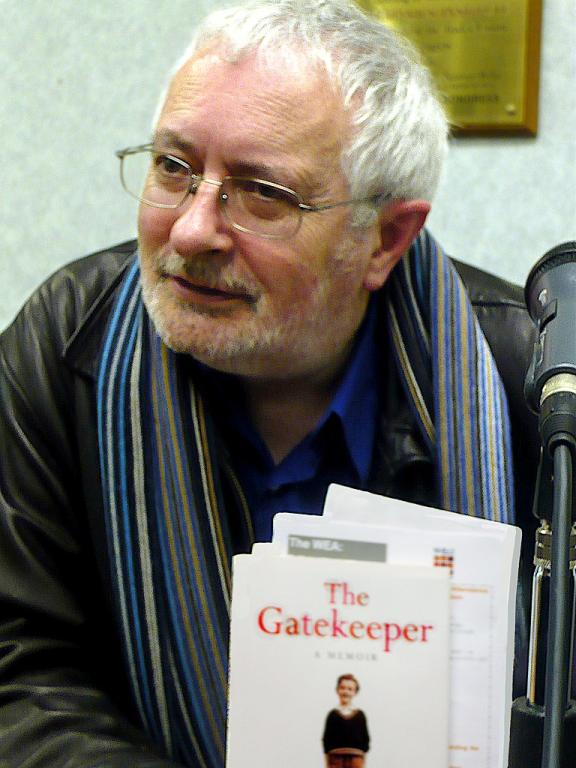

I’ll be on the Interpreter Radio Show later this evening. I’m looking forward to the conversation.

***

Some time ago, I read Terry Eagleton, Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009). The book is based on the 2008 Dwight H. Terry Lectures that Eagleton delivered at Yale University.

A British literary critic and a committed Marxist radical, Eagleton is both stimulating and provocative and, from my vantage point, often seriously wrong. I don’t think he’s a theist; he’s certainly not a mainstream Christian. In particular, he’s not a fan of Latter-day Saints or of the doctrines of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Quite a few years ago, he visited Brigham Young University, leading a smallish faculty seminar for a week or two in which I participated. I recall enjoying it, but I had the distinct impression that he was quite unimpressed with us and even somewhat hostile. And, in fact, he gets in a dig at BYU on page 59 of Reason, Faith, and Revolution.

All of that notwithstanding, I enjoyed the passage that I quote below. While I’m not committed to the notion that Jesus was married, I’m also not . . . umm, wedded to the idea that Jesus was celibate, let alone to the explanation for that putative celibacy that Eagleton (in company with many others) offers. So what did I like about the passage? I found myself thinking, as I read it, not about a permanently celibate professional clergy but about our young missionaries, who forego dating for eighteen months to two years in order to serve, even while the overall ideal for Latter-day Saints is eventual temple marriage and a family:

If self-denial is not an end in itself for Christianity, neither is celibacy. Jesus was probably celibate because he believed that the kingdom of God was about to arrive any moment, which left no time for mortgages, car washes, children, and other such distracting domestic phenomena. This brand of celibacy, however, is not hostile to sexuality as such. On the contrary, it sees giving up sex as a sacrifice, and sacrifice means abandoning something you hold precious. It is no sacrifice to give up drinking bleach. When Saint Paul looks for a sign (or “sacrament”) of the future redeemed world, he offers us the sexual coupling of bodies. It is marriage, not celibacy, which is a sacrament. Fullness of life is what matters; but working for a more abundant life all round sometimes involves suspending or surrendering some of the good things that characterize that existence. Celibacy in this sense is a revolutionary option. Those who fight corrupt regimes in the jungles of Latin America want to go home, enjoy their children, and resume a normal life. The problem is that if this kind of existence is to be available to everyone, the guerrilla fighter has to forego such fulfillments for the moment. He or she becomes what the New Testament calls “a eunuch for the kingdom.” The worst mistake would be to find in this enforced austerity an image of the good life as such. Revolutionaries are rarely the best image of the society they are working to create. (25-26)

A bit more from Eagleton’s 2008 Reason, Faith, and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate:

Dawkins falsely considers that Christianity offers a rival view of the universe to science. Like the philosopher Daniel C. Dennett in Breaking the Spell, he thinks it is a kind of bogus theory or pseudo-explanation of the world. In this sense, he is rather like someone who thinks that a novel is a botched piece of sociology, and who therefore can’t see the point of it at all. Why bother with Robert Musil when you can read Max Weber? . . .

Dawkins makes an error of genre, or category mistake, about the kind of thing Christian belief is. He imagines that it is either some kind of pseudo-science, or that, if it is not that, then it conveniently dispenses itself from the need for evidence altogether. He also has an old-fashioned scientistic notion of what constitutes evidence. Life for Dawkins would seem to divide neatly down the middle between things you can prove beyond all doubt, and blind faith. He fails to see that all the most interesting stuff goes on in neither of these places. Christopher Hitchens makes much the same crass error, claiming in God Is Not Great that “thanks to the telescope and the microscope, [religion] no longer offers an explanation of anything important.” But Christianity was never meant to be an explanation of anything in the first place. It is rather like saying that thanks to the electric toaster we can forget about Chekhov. (6-7)

One can hardly fail to be reminded in this context of an exchange in C. S. Lewis’s early novel The Pilgrim’s Regress — a book that seems to me more prescient with each passing year. The conversation revolves around the “Landlord,” who, in Lewis’s allegory, represents God:

“But how do you know there is no Landlord?”

“Christopher Columbus, Galileo, the earth is round, invention of printing, gunpowder!!” exclaimed Mr. Enlightenment in such a loud voice that the pony shied.

“I beg your pardon,” said John.

“Eh?” said Mr. Enlightenment.

“I didn’t quite understand,” said John.

“Why, it’s plain as a pikestaff,” said the other.

“Your people in Puritania believe in the Landlord because they have not had the benefits of a scientific training. For example, I dare say it would be news to you to hear that the earth was round-round as an orange, my lad!”

“Well, I don’t know that it would,” said John. feeling a little disappointed. “My father always said it was round.”

“No, no, my dear boy,” said Mr. Enlightenment, “you must have misunderstood him. It is well known that everyone in Puritania thinks the earth flat. It is not likely that I should be mistaken on such a point. Indeed, it is out of the question.”

(C. S. Lewis, The Pilgrim’s Regress: An Allegorical Apology for Christianity, Reason, and Romanticism [Grand Rapids, MI.: Ecrdmans. 1992], 20-21 .)

Aw heck. Eagleton is simply quotable. Here’s another:

I suppose that where science and religion come closest for the Christian is not in what they say about the world, but in the act of creative imagination which both projects involve — a creative act which the believer finds the source of in the Holy Spirit. Scientists like Heisenberg or Schrödinger are supreme imaginative artists, who when it comes to the universe are aware that the elegant and beautiful are more likely to be true than the ugly and misshapen. From a scientific standpoint, cosmic truth is in the deepest sense a question of style, as Plato, the Earl of Shaftesbury, and John Keats were aware. And this is at least one sense in which science is thoroughly and properly value-laden. (7)

[In this context, an article titled “In Search of God’s Perfect Proofs: The mathematicians Günter Ziegler and Martin Aigner have spent the past 20 years collecting some of the most beautiful proofs in mathematics” might be relevant.]

Science is properly atheistic [as a matter of methodology]. Science and theology are for the most part not talking about the same kind of things, any more than orthodontics and literary criticism are. This is one reason for the grotesque misunderstandings that arise between them. (9-10)

The difference between science and theology, as I understand it, is one over whether you see the world as a gift or not; and you cannot just resolve this just by inspecting the thing, any more than you can deduce from examining a porcelain vase that it is a wedding present. (37)

[I]t is scarcely a novel point to claim that for the most part Ditchkins [Ditchkins is Eagleton’s amalgamation of Christoper Hitchens and Richard Dawkins] holds forth on religion in truly shocking ignorance of many of its tenets — a situation I have compared elsewhere to the arrogance of one who regards himself as competent to pronounce on arcane questions of biology on the strength of a passing acquaintance with the British Book of Birds. . . . As Denys Turner remarks, “It is indeed extraordinary how theologically stuck in their ways some atheists are.” (49)

Eagleton refers to Daniel Dennett’s commission of

the Ditchkins-like blunder of believing that religion is a botched attempt to explain the world, which is like seeing ballet as a botched attempt to run for a bus. (50)

It is, in fact, entirely logical that those who see religion as nothing but false consciousness should so often get it wrong, since what profit is to be reaped from the meticulous study of a belief system you hold to be as pernicious as it is foolish? . . . So it is that those who polemicize most ferociously against religion regularly turn out to be the least qualified to do so, rather as many of those who polemicize against literary theory do not hate it because they have read it, but rather do not read it because they hate it. (51-52)

It’s hard not to be reminded here of the 1957 quip from the Catholic sociologist Thomas O’Dea, that “the Book of Mormon has not been universally considered by its critics as one of those books that must be read in order to have an opinion of it.”

***

As you can easily see, I’ve been assembling and organizing my notes for future writing projects. I’m pretty excited about them. I hope that health (so far very good) and time (so far still too cluttered) will permit.