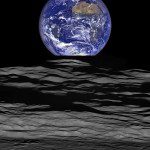

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Herewith, I post another brief set of preliminary notes for (this time) a couple of chapters in my projected book on the Beatitudes. The first two entries in this littler series are “Introducing a Blog Focus for the Sabbath” and ““Blessed are the poor in spirit.”” So here, for whatever it’s worth, is my third installment:

In the King James Version of the Bible, Matthew 5:4 reads as follows: “Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted [παρακληθήσονται].”

The Greek word παρακληθήσονται (in transliteration, paraklēthēsontai) is the term that is rendered in the KJV as “they shall be comforted.” It might perhaps ring a bell even with non-readers of Greek: The Holy Ghost is commonly called the “Comforter.” The first place in the Bible where that term is used in that sense is John 14:16-17:

“And I will pray the Father, and he shall give you another Comforter [παράκλητον], that he may abide with you for ever; even the Spirit of truth; whom the world cannot receive, because it seeth him not, neither knoweth him: but ye know him; for he dwelleth with you, and shall be in you.”

The word that the KJV renders as “Comforter” is παράκλητος [Latin paracletus], which often shows up even in English as “[the] Paraclete.” It might also plausibly be translated as “helper” or “advocate.” In any case, it’s clearly a close relative of the Greek verb in Matthew 5:4, which suggests, quite truthfully, that mourners will — or, at least, can — receive the Spirit, the Comforter.

This is certainly true for believers. Because of the assurance of life beyond the grave, and because of the miraculous defeat of death effected by the resurrection of Christ, they can have confidence that mourning is not the final word. To borrow language from the Psalmist, “weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning” (Psalm 30:5). And resurrected life won’t merely be a resumed life. It will be a glorified life. Moreover, as the Prophet Joseph Smith testified, “All your losses will be made up to you in the resurrection. By the vision of the Almighty I have seen it.”

In the meantime, though, our confidence in the future making-right of all things can and will be sorely tried and wrenchingly tested. (For some thoughts on that, see my recent remarks to the U.S. Hazāra Conference 2022, which have now been published as “Beautiful Patience.”). Many of us have asked ourselves the perpetual question implicitly posed by the biblical Job:

“The tabernacles of robbers prosper, and they that provoke God are secure.” (Job 12:6)

I remember when I myself began, as a teenager, to grow serious about the gospel. I quickly discovered that, where some of my high school friends could get drunk and be immoral and swear and do everything else with a seemingly clear conscience and in apparent happiness, I agonized over being late to priesthood meeting. It wasn’t fair. My newly-hypersensitive conscience seemed to make me less happy than they were!

I was envious at the foolish, when I saw the prosperity of the wicked . . . They are not in trouble as other men; neither are they plagued like other men . . . Their eyes stand out with fatness: they have more than heart could wish . . . Behold, these are the ungodly, who prosper in the world; they increase in riches.

Verily I have cleansed my heart in vain, and washed my hands in innocency.

For all the day long have I been plagued, and chastened every morning. (Psalm 73:3, 5, 7, 12-14)

Your words have been stout against me, saith the Lord. Yet ye say, What have we spoken so much against thee?

Ye have said, It is vain to serve God: and what profit is it that we have kept his ordinance, and that we have walked mournfully before the Lord of hosts?

And now we call the proud happy; yea, they that work wickedness are set up; yea, they that tempt God are even delivered.

Then they that feared the Lord spake often to one another: and the Lord hearkened, and heard it, and a book of remembrance was written before him for them that feared the Lord, and that thought upon his name.

And they shall be mine, saith the Lord of hosts, in that day when I make up my jewels; and I will spare them, as a man spareth his own son that serveth him.

Then shall ye return, and discern between the righteous and the wicked, between him that serveth God and him that serveth him not. (Malachi 3:13-18)

Well, that’s a hasty first pass at Matthew 5:4. We now move on to an even hastier glance at the verse immediately following:

The King James translation of Matthew 5:5 is: “Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.”

The first thing that leaps out here is the positive valuation of “the earth.” This is very biblical. Consider, for example, the final verse of the creation narrative given in Genesis 1:

“And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good. And the evening and the morning were the sixth day.”

Such a positive attitude wasn’t universally shared in antiquity, though, and it isn’t universally shared today. In his dialogue Phaedo, for instance, Plato has Socrates refer to philosophy as “the practice of death.” What he seems to have meant by this is that the philosopher tries to remove herself from the distractions of the sensible world — in effect, to will a separation of mind or spirit from body — in order to reflect more perfectly on the eternal, unchanging, and invisible world of the Platonic “Forms” or “Ideas.”

With this sort of attitude, who would want to “inherit the earth”? Why, for that matter, would anybody want to be resurrected? Who would want that old, distracting physical body back? Who, after the liberation of death, would want to return to dragging a physical carcass around? Consider, too, this passage about the great founder of Neoplatonism, Plotinus (204/5-270 AD), from the first chapter of On the Life of Plotinus and the Arrangement of His Work, by his student, admirer, and editor Porphyry of Tyre (ca. 234-ca. 305 AD):

“Plotinus, the philosopher our contemporary, seemed ashamed of being in the body. So deeply rooted was this feeling that he could never be induced to tell of his ancestry, his parentage, or his birthplace. He showed, too, an unconquerable reluctance to sit to a painter of a sculptor, and when Amelius persisted in urging him to allow of a portrait being made he asked him, ‘Is it not enough to carry about this image in which nature has enclosed us? Do you really think I must also consent to leave, as a desired spectacle to posterity, an image of the image?’”

Perhaps influenced by Platonism, the gnostics wanted nothing more than to escape this world. And, curiously, they have been followed by generations of Christians — as is illustrated, I think, in hermeticism and monasticism, but not only there. Is a resurrected physical body really necessary for, or even relevant to, the notion of salvation as “beatific vision” (understood by some, at least, as a largely if not purely intellectual contemplation of God)? Would it not, rather, be if anything an obstacle and a distraction?

However, what about the “meek” who are pronounced “blessed” in Matthew 5:5?

Meek comes from an old Germanic root meaning “mild,” “gentle,” or “soft.”[i]. The Greek is πραεῖς, meaning not only “meek” but “gentle” or, in the case of animals, “tame.” It can also have the sense of “gentle,” “low,” or “soft” when used with regard to sounds.

But we are certainly not talking, here, of anything weak or Casper Milquetoast:

“Now the man Moses was very meek, above all the men which were upon the face of the earth.” (Numbers 12:3)

In fact, Jesus describes himself as “meek and lowly in heart” (Matthew 11:29).

[i] The English word meek is ultimately related to the word mucus, astonishingly enough. See Eric Partridge, Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English (New York: Greenwich House, 1983), 394.

There’s lots more to be said about these two verses, obviously, but that’s enough for today.