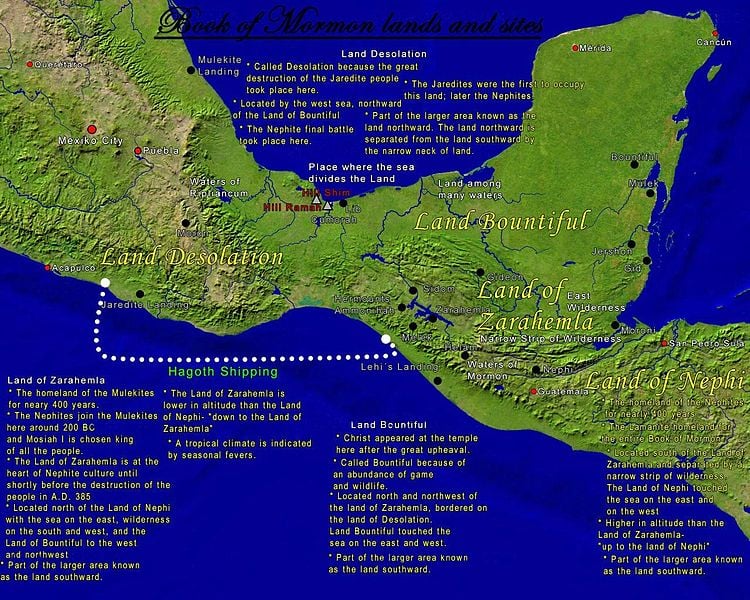

The sadly necessary Neville-Neville Land blog posted a useful entry the other day on “Photos of Mesoamerican sites in the 1963–1981 missionary edition of the Book of Mormon.” That’s the edition with which I pretty much grew up and came to adulthood (if, indeed, I ever have come to adulthood). And it serves to illustrate my contention that, during my childhood and youth, Latter-day Saints — and certainly the Latter-day Saints that I knew — typically understood phrases like lands of the Book of Mormon to refer primarily to Latin America (and, specifically, Central America or Mesoamerica). I don’t think that I ever heard anybody advocate an Upper Great Lakes geographical model. For most of us, though, it was rather vague. When Church members heard mention of the Book of Mormon’s narrow neck of land, they thought — certainly I thought — of the Isthmus of Panama. It seemed pretty obvious, after all. All that was needed was the quickest glance at a map of the Americas, right? Equally obvious were the land northward and the land southward. North America and South America. Of course.

Now, I still had some sort of vague sense that the Americas were all involved, largely if not altogether in their entirety. And so, I think, did most Latter-day Saints back then. After all, the final battle was fought at the Hill Cumorah in upstate New York, and that’s where the mortal Moroni buried the plates and where, under the resurrected Moroni’s direction, Joseph Smith recovered them.

But I, at least, hadn’t really thought much about any of this. So, as I said in my previous blog entry “The Book of Mormon, Mesoamerica, and Me,” David A. Palmer’s In Search of Cumorah: New Evidences for the Book of Mormon from Ancient Mexico (1981) and, even more so, John L. Sorenson’s An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (1985) were paradigm-transforming for me.

Some continue to insist that John Sorenson’s “limited geographical model” or “limited Tehuantepec model” was devised in a desperate bid to so shrink the Lehite and Jaredites demographically and geographically that they would be invisible to the analysis of Amerindian DNA and impervious to genetic research. But this is sheer uninformed (and arguably defamatory) silliness.

As I pointed out in a 2004 article entitled “On the New World Archaeological Foundation,” that organization was established at Brigham Young University in 1952 in order to foster Mesoamerican exploration, which University faculty had already been pursuing since 1948 for reasons directly related to their understanding of the Book of Mormon. It reflected the Mesoamerican-focused thinking of such formative figures as M. Wells Jakeman, Ross T. Christensen, Milton R. Hunter, and, yes, Thomas Stuart Ferguson. John Sorenson’s Mesoamerican model was formed during those early years and under those influences. But Francis Crick and James Watson only discovered the three-dimensional double-helix structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, and it doesn’t seem that anthropological genetics really got underway until the late 1980s or early 1990s. (See Michael H. Crawford and Kristine G. Beaty, “DNA fingerprinting in anthropological genetics: past, present, future,” Investigative Genetics 4/23 [2013].)

And, anyway, as a certain hyperzealous and quite unpleasant “Heartlander” is wont to point out with an animus that makes sense only to him, it was a member of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints by the name of L. E. Hills who may have been the first person to have published anything like a limited Mesoamerican geographical model for the Book of Mormon based on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Mr. Hills died in 1925, but he had apparently introduced a map of his geographical model back in 1917 — when Francis Crick was just one year old and James Watson’s birth was still eleven years off in the future.

What impelled John Sorenson to constructed a “limited” geography for the Book of Mormon wasn’t a desire to escape the prying eyes of as-yet unborn genetic anthropologists. Instead, it was the distances mentioned in the text itself. Quite simply, they’re never very large in any direction. While people who are not paying attention might idly imagine that the Book of Mormon describes a geographical space extending from the Aleutian Islands in the northwest and Hudson’s Bay in the northeast down to Tierra del Fuego in the south, the distances described in the book don’t permit any such thing. Plainly, then, the narrative of the Book of Mormon can’t include or cover all of North, Central, and South America, and the question then becomes “What fairly limited area within North, Central, and/or South America was the setting for the stories of the Nephite, Lamanites, and Jaredites?”

John Sorenson laid all of this out in the opening pages of his 1985 Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon. It’s both very clear and entirely sufficient to justify his idea of a “limited geography”; there’s absolutely no need to invoke mysterious additional factors to account for it, or to suggest nefarious plots to escape scientific scrutiny. Indeed, if this isn’t a case for Ockham’s Razor, I can’t imagine what would be. Although William of Ockham never actually used these precise words, the “Razor” is frequently cited as Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem, which can be rendered as “Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity.” In other words, if a is entirely sufficient and perfectly adequate to explain x, there is no call to invoke supplemental explanations b and c.

A limited geographical model for the Book of Mormon shouldn’t really be such a great shock — and, if I’m not mistaken, the idea is accepted even by the majority of “Heartlanders.” Most of the stories of the Old Testament and the New Testament, after all, take place within a strikingly small area between Dan in the north and Be’er-Sheva (Beersheba), about 136 miles to the south, from the Great Sea (the Mediterranean) to the River Jordan. Israel is, as I can promise you from actual personal acquaintance with it, a rather tiny country. At its widest, it’s only about seventy-one miles across.

Mark Twain grew up along the Mississippi River, the Father of Waters. So when he finally saw the Jordan, according to his travel memoir Innocents Abroad, he wasn’t exactly overwhelmed:

When I was a boy, I somehow got the impression that the river Jordan was four thousand miles long and thirty-five miles wide. It is only ninety miles long, and so crooked that a man does not know which side of it he is on half the time. In going ninety miles it does not get over more than fifty miles of ground. It is not any wider than Broadway in New York [which, in his day, was very narrow].

There is the Sea of Galilee and this Dead Sea—neither of them twenty miles long or thirteen wide. And yet when I was in Sunday School I thought they were sixty thousand miles in diameter.

Travel and experience mar the grandest pictures and rob us of the most cherished traditions of our boyhood. Well, let them go. I have already seen the Empire of King Solomon diminish to the size of the State of Pennsylvania; I suppose I can bear the reduction of the seas and the river. [Chapter LV]

Posted from Jerusalem, Israel