I discovered late last night that a lengthy interview that I did a few weeks back for the Ireland-based podcast Mormonism with the Murph is now up on line, in two parts:

“Evidence for the Book of Mormon with Dan Peterson”

“Responding to criticisms against the Book of Mormon with Dan Peterson”

As has happened every single Friday since early August 2012, a new article has appeared in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship: “Theosis in the Book of Mormon: The Work and Glory of the Father, Mother and Son, and Holy Ghost,” written by and

Abstract: While some scholars have suggested that the doctrine of theosis — the transformation of human beings into divine beings — emerged only in Nauvoo, the essence of the doctrine was already present in the Book of Mormon, both in precept and example. The doctrine is especially well developed in 1 Nephi, Alma 19, and Helaman 5. The focus in 1 Nephi is on Lehi and Nephi’s rejection of Deuteronomist reforms that erased the divine Mother and Son, who, that book shows, are closely coupled as they, the Father, and Holy Ghost work to transform human beings into divine beings. The article shows that theosis is evident in the lives of Lehi, Sariah, Sam, Nephi, Alma, Alma2, Ammon2, Lamoni, Lamoni’s wife, Abish, and especially Nephi2. The divine Mother’s participation in the salvation of her children is especially evident in Lehi’s dream, Nephi’s vision, and the stories of Abish and the Lamanite Queen.

The Larsen and Wright article is accompanied by “Interpreting Interpreter: Book of Mormon Theosis,” which was written by Kyler Rasmussen:

This post is a summary of the article “Theosis in the Book of Mormon: The Work and Glory of the Father, Mother and Son, and Holy Ghost” by Val Larsen and Newell D. Wright in Volume 56 of Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship. An introduction to the Interpreting Interpreter series is available at https://interpreterfoundation.org/interpreting-interpreter-on-abstracting-thought/.

The Takeaway: Larsen and Wright argue that a number of Book of Mormon passages imply the doctrine of theosis – the ability to become like God. This includes the existence of a divine council, the implication that we can be enrolled in that same council through baptism and the Atonement, the transcendent experiences of people like Alma2 and Lamoni, and human involvement in the work and power of the divine.

Incidentally, President Dallin H. Oaks of the First Presidency and his wife, Sister Kristen M. Oaks, are scheduled to present a youth fireside this Sunday night. I’m told that it will likely address a number of what (to coin a wholly original new phrase) I’m going to call “hot-button issues.”

And now I write up a few notes for my future use, and share them with you.

Are the New Testament gospels infallible or inerrant? I don’t think that Latter-day Saints have much invested in a positive answer to that question. And there seems at least some reason to answer No. Consider this quotation from Robert J. Hutchinson, Searching for Jesus: New Discoveries in the Quest for Jesus of Nazareth — And How They Confirm the Gospel Accounts (Nashville: Nelson Books, 2015):

For example, Matthew says that Jesus was born before Herod the Great died (2:1) in 4 BC, while Luke says that he was born when Quirinius, the governor of Syria, ordered a census to take place (2:2), which occurred in AD 6. One of the gospel writers, probably Luke, appears to have gotten at least the year of Jesus’s birth wrong. (7)

Still, although we care little or nothing about inerrancy, we typically (and, in my view, rightly) take a very high view of the overall historical accuracy of the gospels.

For now, I want to look at the gospel of John. (Right now, I’ll be drawing substantially for this, but not solely, on Searching for Jesus, pages 4-5.) As is widely known, the four New Testament gospels are typically divided into two groups — the three “synoptic” gospels on the one hand and, on the other, the gospel of John. One of the unique characteristics of John is its “high Christology.” What that means is that John treats Jesus as a divine god-man rather than merely as a Jewish prophet or sage.

With that in mind, modern critical scholars have overwhelmingly viewed John as the product of an evolution in Christian thinking and, thus, as fairly late — dating to perhaps the early second century. Accordingly (and also because a view of Jesus as prophet and sage has typically been regarded as original and early), its historical value has been regarded as, at best, limited. Some have even suggested that its portrayal of Jesus as divine reflects the influence of a pagan milieu that recounted stories of multiple god and, perhaps more relevantly, of demigods. And the prologue of John 1 plainly shares thematic elements with the Middle Platonism of Philo of Alexandria. As the widely respected British New Testament scholar James D. G. Dunn has written, for a “hundred years the character of John’s Gospel as a theological, rather than a historical document, became more and more axiomatic for [New Testament] scholarship.” [James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, vol. 1 (Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 41]

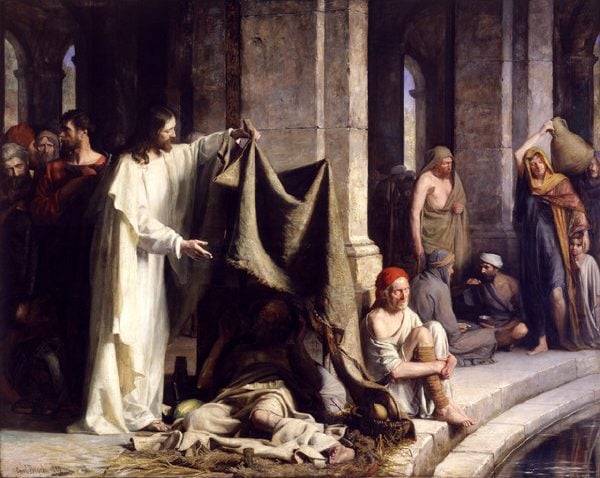

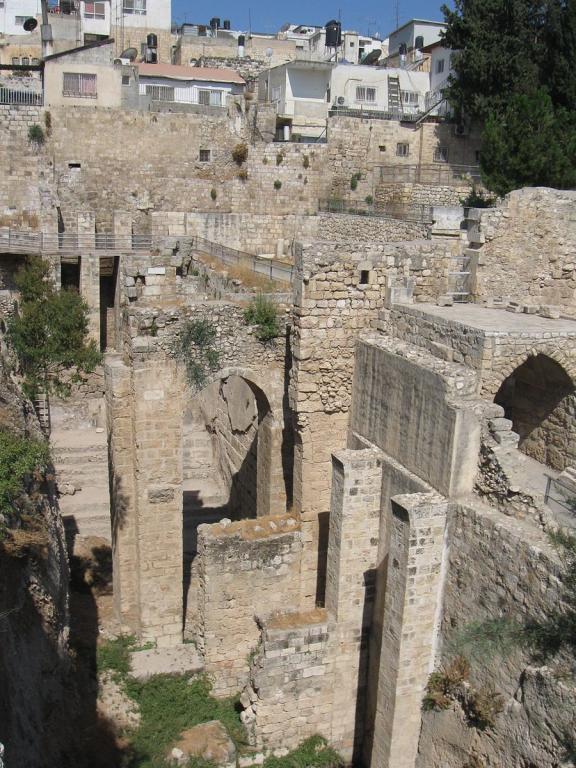

And yet, and yet . . . John contains unique historical details that appear nowhere else, neither in the rest of the New Testament nor in ancient secular sources. The case of the pool of Bethesda will serve to illustrate this. A number of critical scholars once pointed to the story of the healing of the man at the Pool of Bethesda, recounted in John 5, as something that John simply made up. But no longer.

Tourists in today’s Jerusalem — very much including the groups that I myself lead — often enter into the Old City via St. Stephen’s Gate (which is also commonly known as Lions’ Gate) in order to access the famous traditional Via Dolorosa. First, though, they see the large complex of the Church of St. Anne on their right. The church itself is historically interesting, having been built by the Crusaders in the early twelfth century on one of the traditional sites of the childhood home of the Virgin Mary. Later, it was transformed into an Islamic madrasa by the great Sultan Saladin (Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn) after his reconquest of the city in AD 1187. In 1856, grateful for French support during the Crimean War, the Ottoman sultan Abdülmecid I presented it to Napoleon III, and it is now, evidently, actual French territory in some technical legal sense. It is under the custodianship of the “Missionaries of Africa,” the Pères Blancs or “White Fathers,” so called because of the color of their robes. It also has phenomenal acoustics, and visiting Christian tour groups (mine included) often take turns singing in it.

Also within the courtyard, just beyond St. Anne’s, are, yes, the very deep pools of Bethesda. These were found by accident in 1871, when restoration work was undertaken on the church. They had been buried by the ruins of Byzantine and Crusader churches that had been built over them, and lost to memory.

The first of the two pools, it seems, was constructed in the eighth century BC, when a dam was built across the Beth Zetha Valley that actually comes into the Old City itself. (2 Kings 18:17 appears to refer to it.). The second pool was built during the second century before Christ in order to provide the temple area with more water, probably for washing sheep for the sacrificial liturgy of the temple. (St. Stephen’s Gate or Lions’ Gate is also sometimes called the “Sheep Gate.”) Eventually, the pool came to be used as a healing bath, rather like a spa.

The five porticoes mentioned in John 5 have disappeared. But St. Jerome, who lived in nearby Bethlehem in the early fifth century, described the pools in detail:

Bethesda, a pool of Jerusalem . . . had five porticoes; [local people] show a double pool, one of which is fed with winter rainfalls; surprisingly, the water of the other appears reddish as if tainted by blood and thus attests its ancient use by the priests who, as it is said, would come here to wash the [sacrificial] victims, and this is where its name comes from. [Saint Jerome, De situ et nominibus Hebraicorum locorum, vol. 23, cited in John J. Rousseau and Rami Arav, Jesus and His World: An Archaeological and Cultural Dictionary [Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995], 155.

“In short,” summarizes Robert Hutchinson,

John reveals an intimate knowledge of Jerusalem that led Israeli archaeologist Rami Arav and John Rousseau, a fellow of the Jesus Seminar and research associate at the University of California, Berkeley, neither conservative Christians, to conclude that “the primary author of the Gospel of John was probably an eyewitness to several events in the life of Jesus” and was “well acquainted with Jerusalem and its surroundings.” (5)

I read his book The Reason for God soon after it was first published, partly because I thought that there was much that Latter-day Saints might learn from his approach to reaching souls in the exceptionally difficult urban environment of New York City. I continue to think so: “Died: Tim Keller, New York City Pastor Who Modeled Winsome Witness”

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

And, last but not least, today’s appalling contribution from the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™: “Family History Can Improve Psychological Well-being of Young Adults, Says BYU Study: Participating in family history research reduces students’ anxiety by 20%, increases self-esteem by 8%”