(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I think that I failed to mention this item when it appeared on Wednesday. It was first delivered on Saturday, 14 March 2015, during the Interpreter Foundation’s 2015 conference on Exploring the Complexities in the English Language of the Book of Mormon:

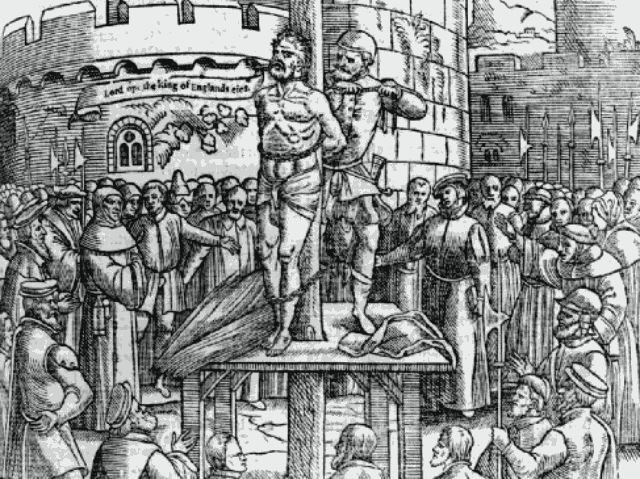

Conference Talks: “Charity, Priest, and Church versus Love, Elder, and Congregation: The Book of Mormon’s connection to the debate between William Tyndale and Thomas More,” given by Jan J. Martin

Thomas More and William Tyndale were staunch opponents but they did agree on two things: (1) that language and theology were inseparable, and (2) that errors of language could lead to serious errors in theology. These two commonalities fueled their famous debate about Tyndale’s translation of the Greek words presbuteros, ekklēsia, and agapē into English as elder, congregation, and love. Though three centuries separate the Book of Mormon from More and Tyndale, that gap will be closed as the Book of Mormon’s use of charity/love, priest/elder, and congregation/church are analyzed within a sixteenth-century context.

As I recently explained, I’ve lately been seeking to use my blogging time to create notes for myself from some of my reading. Such notes have been piling up, so this is a more efficient use of my time. For this particular blog entry, I’m taking some excerpts from Paul Helm, Faith With Reason (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003).

Religious belief has to meet and sustain philosophical scrutiny as does any other belief; nothing about religion purchases immunity from this. . . . But at the same time religious epistemology has also to respect the contours of religion, just as, say, moral epistemology has to recognize the contours of morality. It has to recognize that if some religious beliefs are reasonable they may well be so in virtue of respecting the distinctive subject-matter of the belief, and refusing to allow that it is reducible to some other subject-matter. What I refer to as the James Principle, the claim of William James that ‘A rule of thinking which would absolutely prevent me from acknowledging certain kinds of truth, if those kinds of truth were really there, would be an irrational rule’, has to be carefully observed. (xiii)

[The reference is to William James, ‘The Will to Believe’, in The Will to Believe an Other Essays (New York, 1917), 28.]

It is fundamental to the consideration of the rationality of a belief that an investigation into the truth of a claim, the evidence that is considered relevant, should be conditioned by the type of claim that is being made. . . .

It is important to keep an open mind, and not an empty mind. An open mind is one that is sensitive not only to general canons of rationality or reasonableness, but also to the unique features of what is being enquired into. (14)

A cumulative case is a set of arguments which reinforce each other, as different lines of evidence might reinforce the conviction that a particular person committed a crime. (xiv)

. . . one reason for failure to believe may be that the one who fails to believe has an interest in not believing. This chapter [chapter 5] explores the connection between having an interest and the appreciation of evidence. There are three questions here: Are at least some failures to believe like the failure to recognize an obligation, like having a moral block? Are other failures like situations where one recognizes an obligation but, due to weakness of will, fails to honour it? And is it always rational, in the interests of objectivity, to suppress the influence of our moral nature as far as possible in our assessment of evidence? (xv)

[One view:] Faith does not involve belief. Faith is ‘faith in’, not ‘faith that’; faith in God cannot be understood in terms of a set of beliefs that. (4)

. . . the two elements of faith, the doxastic and the fiducial, the doxastic element is primarily evidential (and involuntary), while the trusting that that is exercised is primarily voluntary and capable of being morally assessed. For trusting is a disposition expressed in action, a disposition based upon a particular conception of the good. And so faith, including religious faith, has a peculiar combination of passivity and activity about it; its evidential aspect is passive, its fiducial element is active, and it is this active element which is sufficient to make faith an action. (16)

In order to illustrate the two sides of faith, the doxastic and the non-doxastic, let us suppose for the moment that some version of strong foundationalism is true, and that the existence of God is justified by reference to these foundations. That is, let us take it that there are optimal evidential grounds for belief in God. And let us further suppose that the believer has similarly strong reasons to believe that God is worth trusting. It does not follow from these two sets of facts, facts about evidence and facts about the worthwhileness of trust, that God will actually be trusted. Whether or not he will be trusted depends upon the will or endeavour of the one who has the evidence and who has made appropriate judgements about the worth of what there is good evidence for.

So for there to be faith in God two other factors are necessary besides evidence, so it seems to me. The first is the belief that there is something to trust God for; and then there must be the actual exercise of trust. To have faith in God, on this understanding of what faith is, is not to believe, against all the odds, that God exists and in addition to trust in him; it is solely to trust him on the basis of evidence and for the fulfillment of certain needs or goals. So having beliefs about X, even beliefs about X‘s trustworthiness, is distinct from trusting X. For even if trusting is primarily an action, the doxastic component of faith and the worthiness of faith do not ensure the occurrence of the action, since weakness of will may prevent this. (16-17)

It might be argued that since trust is necessarily oriented to the future — one cannot now trust someone to have done something — and that as the past and present never entail the future, trust always goes beyond the evidence. (18)

The difference between belief and faith is the element of trust . . . (20)

To follow the helpful classification of William Lad Sessions, there are six models of faith: as personal relationship, as belief, as attitude, as confidence, as devotion, and as hope (The Concept of Faith, ch. 2). It is part of my argument that these models are not all exclusive of each other. (15, note 14)