You might justly view yesterday’s blog entry here as a full-length installment from the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™. In a very real sense, that is exactly what it was, and I hope that you’ll take the opportunity not only to buy something yourself but to call the opportunity to the attention of others.

I already called attention a few days back to a brief excerpt from an Interpreter Foundation interview with Elder Dale G. Renlund of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and his wife, Sister Ruth L. Renlund. But now that selection from the interview is up on the blog of the Interpreter Foundation, embedded in an entry written by Dr. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. And, anyway, some of you may have missed it, and you really shouldn’t: “Not by Bread Alone: “We Absolutely Fell in Love with the People”: A New Short Film About Africa with Elder and Sister Renlund: Blog Post #3″

For more information on the “Not by Bread Alone: Stories of the Saints in Africa” series, go to https://notbybreadalonefilm.com/en/

For more information in French, go to https://notbybreadalonefilm.com/fr/

To see all of our posts about the Church in Africa, go to https://interpreterfoundation.org/category/africa/

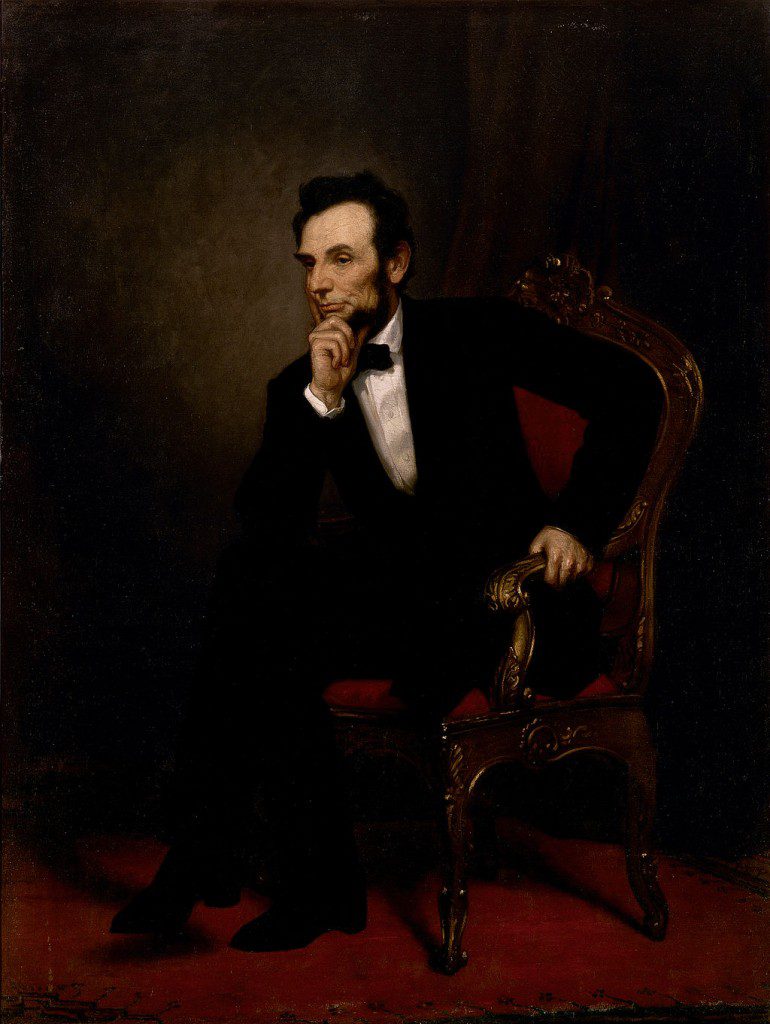

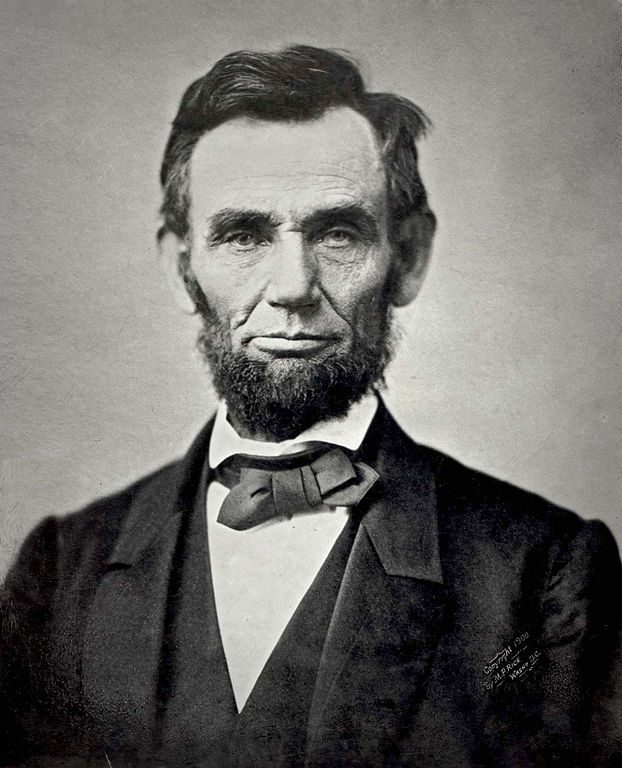

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image). He had a year and a half yet to live.

Today is the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which was given on 19 November 1864. It is one of the most powerful pieces of prose not only in the American political tradition but, in my view, in the English language as a whole — and you’ll incur no injury by at least skimming through it. For your convenience, I include the full text here:

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

“But in a larger sense we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us,that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion, that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

I’m in a very Lincolnian mood right now — although Virginia wasn’t exactly the “Land of Lincoln” in his day, reminders of the Civil War and of the Revolution and the American Founders and their ideas and ideals are all around me — and, accordingly, I’m going to share with you another brief prose masterpiece that evidently flowed from Mr. Lincoln’s pen.

In the autumn of 1864, Governor John A. Andrew of Massachusetts wrote to President Lincoln asking him to express condolences to Mrs. Lydia Bixby, a widow whom he believed (incorrectly, as it turned out) to have lost five sons during the Civil War. Here is the text of the letter that was sent from the White House:

Executive Mansion,

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.Dear Madam,–

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln

And then there is President Lincoln’s remarkable Second Inaugural Address, which he delivered on 4 March 1865 during the ceremonies accompanying his second inauguration as President of the United States of America. The Civil War was very nearly at an end. Robert E. Lee would surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on 9 April, and the last military department of the Confederacy effectively surrendered on 26 May. (Unfortunately, in the meantime — on 14 April 1863, only five days after General Lee’s surrender, just a month and ten days after his second inauguration — President Lincoln was martyred at the hand of John Wilkes Booth.)

Strikingly, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address isn’t triumphant. It isn’t giddy at the clearly imminent Union victory. Instead, it’s rather noticeably reflective and even sad. It acknowledges the vast and horrible evil of slavery but calls for mercy and charity. (How different might Reconstruction, and subsequent American history altogether, have been, had he lived to serve out his second term and beyond!) The speech is, to state the obvious once more, truly stunning.

Fellow-Countrymen:

At this second appearing to take the oath of the Presidential office there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement somewhat in detail of a course to be pursued seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of this great conflict which is of primary concern to the nation as a whole, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself, and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war—seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

I’m deeply impressed with Lincoln’s moral seriousness in these passages. I’m deeply impressed by their profoundly spiritual character. I can’t help comparing them to today’s public political discourse and, well, almost wanting to cry.

Posted from Richmond, Virginia