(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Last night, we attended a performance by a string quintet (occasionally joined by a French horn) at the Schloss Mirabell in Salzburg. The palace, which stands with its gardens on the shore of the Salzach River north of the medieval city walls, was built about 1606 by Prince-Archbishop Wolf Dietrich Raitenau as a pleasure palace for him and his mistress, Salome Alt. Not only did he live in the humble manner appropriate to a man of the cloth, but he was amazingly fertile for a priest who had taken a vow of celibacy: According to last night’s program, she bore him either fifteen children (English text) or seventeen (German text).

The night began with a piece by Joseph Haydn, and then the rest was Mozart — culminating in his “Eine kleine Nachtmusik.” The quintet was very good, and they received a deservedly enthusiastic ovation, which they answered with a horn-accompanied rendition of Ennio Morricone’s haunting theme from The Mission. (I liked their version better than this one , which was conducted by Morricone himself.)

With that concert in mind, and still in the spirit of Mozartstadt Salzburg, I think that I’ll post my last entry for now on the question of whether, as the late Christopher Hitchens claimed, religion poisons classical music. The three previous entries may be reviewed here and here and here:

The English composer Sir Edward Elgar (d. 1934) “chose to set to music virtually the whole of the New Testament.”[1] “Few artists in all of history have spent so many years of their life using their gift to enhance the Scriptures, particularly with his huge compositions entitled, The Apostles and The Kingdom.”[2] He wrote a song entitled Chariots of the Lord and oratorios entitled Lux Christi (“Light of Christ”) and Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf, about the epochal conversion of the King of Norway to Christianity, as well as a choral work, The Dream of Gerontius, about the experience of a Christian traveling from this world to the next life. The great Polish pianist (and eventual Polish prime minister) Ignaz Paderewski was once asked “Who is Elgar and where did he study? Was he at any conservatory?” Paderewski said that he was not. “But who was his teacher?” came the next question. “Le Bon Dieu,” replied the pianist.[3]

His principal biographer says that the “church-going self” of the radical American composer Charles Ives (d. 1954) was “conservative to the point of fundamentalism. He was almost in a state of ‘Give me that old-time religion, it’s good enough for me.’”[4] (He even composed a piece called The Revival Service, and another, General William Booth Enters into Heaven, about the founder of the Salvation Army.) “Most of the forward movements of life in general and of pioneers in most of the great activities,” Ives himself remarked as if responding prophetically to Christopher Hitchens, “have been the work of essentially religious-minded men.”[5] He happily anticipated a life beyond death, saying that he wanted to “see and talk to my father.”[6] More than fifty different Christian hymn tunes are quoted in his compositions, and he set several of the biblical psalms to music.

The great modern British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (d. 1958) was also a deeply religious man. One participant in a choir that he led later recalled the tears running down Vaughan Williams’s cheeks as he conducted the portions of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion that recount Peter’s denial and Christ’s crucifixion.[7] Vaughan Williams became editor of the English Hymnbook in 1904, and edited Songs of Praise in 1925. His opera The Pilgrim’s Progress (based on the famous Christian allegorical tale by John Bunyan), the Christmas cantata Hodie (“This Day”), and the orchestral suite Job—A Masque for Dancing have been collectively dubbed his “affirmations of belief” by one his biographers.[8] But they don’t stand alone. He set texts from the English Christian poet George Herbert to music as Five Mystical Songs, composed a Te Deum for the installation of a new archbishop of Canterbury, wrote a Mass in G Minor, created a motet entitled The Souls of the Righteous, and wrote many smaller choral works such as O Taste and See, Dona Nobis Pacem (“Grant Us Peace”), and O Clap Your Hands.

“The more one separates oneself from the canons of the Christian church,” said Igor Stravinsky (d. 1971), “the further one distances oneself from the truth.”[9] “Music comes to reveal itself as a form of communion with our fellow man—and with the Supreme Being.”[10] Among his works are Three Sacred Choruses, written for the Orthodox liturgy, and a Catholic mass, as well as a Symphony of Psalms, The Flood, The Tower of Babel, Abraham and Isaac, Requiem Canticles, Sermon, Prayer, Canticum Sacrum, Credo, an Ave Maria, and a Pater Noster (“Our Father”).

Olivier Messiaen (d. 1992) “was one of the most outspoken Christian composers of all time.”[11] “What impressions do you want to communicate to your listeners?” his biographer Claude Samuel once asked him. Messiaen replied that “The first idea that I wished to express—and the most important, because it stands above them all—is the existence of the truths of the Catholic faith.”[12] His compositions for secular concert halls were just as religiously significant to him as anything he wrote directly for the church. “I wished to accomplish a liturgical act—that is to say, to transfer a kind of divine office, a kind of communal praise to the concert hall.”[13] His Couleurs de la Cite celeste (“Colors of the Celestial City”) is a meditation on the biblical book of Revelation, as is The Quartet for the End of Time, which he composed and premiered in a Nazi prison camp in 1941. His fervent Christian faith is also manifest in his Trois Petites Liturgies de la Presense Divine, his organ work La Nativite de Seigneur (“The Nativity of the Lord”), an orchestral piece entitled Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum, and a piece for organ called Meditations on the Mystery of the Sacred Trinity.

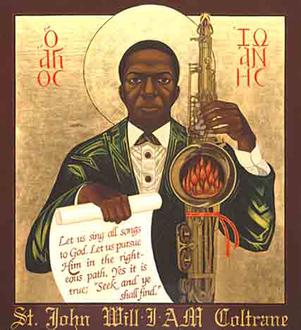

[I didn’t actually finish this little examination of Mr. Hitchens’s dramatic claim that religion poisons everything, but if I ever do so I will be certain to mention Sir John Tavener (1944-2013), a convert to Orthodox Christianity who is known for his extensive output of choral religious works. And I will certainly discuss Arvo Pärt (1935- ), an Estonian who has been called “the world’s greatest living composer and who, like Tavener, is a convert to Eastern Orthodoxy. Wikipedia says of him that “Unlike many of his fellow Estonian composers, Pärt never found inspiration in the country’s epic poem, Kalevipoeg, even in his early works. Pärt said, ‘My Kalevipoeg is Jesus Christ.'” Even the slightest glance at Arvo Pärt’s musical oeuvre will suggest the prominence of religious themes in his compositions. And I will probably include John Coltrane (1926-1967), whose A Love Supreme would be enough, alone and by itself, to qualify him for my list. And here’s a personal favorite: I love the oratorio The Redeemer, by our late friend Robert Cundick (1926-2016). Consider, for example, this part of that oratorio: “He is the Root and the Offspring of David.” The very first Interpreter Foundation venture into filmmaking was a half-hour piece entitled Robert Cundick: A Sacred Service of Music.]

[1] Percy M. Young, Elgar, O. M., A Study of a Musician (London: Collins St. James Place, 1955), 319.

[2] Kavanaugh, Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers, 162.

[3] Ibid., 165

[4] Ibid., 183.

[5] Ibid., 182-3.

[6] Ibid., 183.

[7] Ibid., 172.

[8] Ibid., 174.

[9] Ibid., 189.

[10] Ibid., 191-29.

[11] Ibid., 196.

[12] Claude Samuel, Conversations with Olivier Messiaen (London: Stainer and Bell, 1976), 2.

[13] Robert Sherlaw Johnson, Messiaen (London: M. Dent and Sons Ltd., 1975), 43.

Posted from Göteborg, Sweden