First, two stories that can be taken as pointing in two quite different directions:

(1) As a teenager, I worked every summer for the Southern California construction company that my father owned. He didn’t want me to be or to seem spoiled, so he often made sure that I received the dirtiest, least glamorous, and most onerous assignments that were available. (I sometimes thought that he overdid it.) One of those assignments was to serve as a flagman, telling motorists when they had to wait, when they could proceed, and, most of the time, that they would need to take an alternate route that day.

It was a horrifically boring and terribly tedious job. Except when drivers misbehaved, which was surprisingly often.

One day, we were resurfacing a major street in, I think, Arcadia, or maybe Temple City. A man drove up on the major cross street where I was standing, indicating that his destination was across on the other side. I told him that he could go up one block to either the north or the south and cross there. He said that he wanted to cross right where he was. I said that he couldn’t. He said that he would. I indicated what I thought should have been obvious — that, in crossing over the steaming asphalt before him, he would not only severely damage our work but probably destroy the undercarriage of his car and possibly even pop his tires. He said that he was going to cross, regardless. I said that he was not. He began to roll slowly forward. I stepped in front of him. He continued to roll forward. I didn’t move.

Fortunately, one of our workers, a powerfully-built Mexican-American an ex-Marine whom, when I was small, I had thought to be one of my uncles, saw what was happening and jumped off of his steamroller. He jogged over to the car and offered to break the driver’s neck if he came even one inch closer to me. The driver prudently chose to back up and go around the block.

I tell the story to indicate a sort of obstinate determination that is a feature of my native temperament. When, to me, it’s a matter of principle, I sometimes refuse to budge or back down, even when it might cost me. There are other such stories going back to my very young childhood.

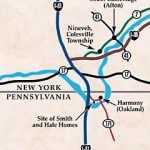

(2) Years ago, I heard the story of a Latter-day Saint meetinghouse that was to be constructed somewhere in the Cornwall area of southwestern England. I’ve never confirmed this story or seen it in writing, but it will serve to illustrate my point even, as is conceivable, if it turns out not to be exactly true.

In the area where the meetinghouse was to be erected, there was a community rule that all roofs must be made of dark gray slate. For some reason, though, somebody in a leadership position in the Church determined that we didn’t want to comply with that rule. So we sued and we won, and ours became the only building in the area with a shingle roof. We won, but I wondered how much we had lost in winning.

I relate these stories in connection with the controversies that are currently aflame about some of our announced temples. (I alluded to a few of these controversies in a post here a couple of days ago. You can learn a bit more about them through the links there. And there are several others.)

Off the top of my head, I’m aware of strenuous opposition, historically speaking, to the building of the Bern Switzerland Temple, the Boston Massachusetts Temple, the Denver Colorado Temple, the Newport Beach California Temple, the Preston England Temple, the Phoenix Arizona Temple, and others. And some of that opposition was explicitly motivated by religious hostility.

Now, I’ll be candid here: It’s difficult for me to see some of the current objections to the tiny Cody Wyoming Temple (e.g., that it will loom over the metropolis of Cody and blot out the night sky) as anything other than at least partially disingenuous. The temple in Cody would be less than 10,000 square feet; I’m betting that there are may be some houses in the area that are larger than that. And it will sit deep within an enclosed area totaling almost 4.7 acres.

And I’ve been to the site of the proposed Lone Peak Nevada Temple, which is really very much out in the boonies. Likewise, the legal argument made on behalf of the Church for a zoning variance for the McKinney Texas Temple — see my blog link above — seems to me a powerful one.

I have no idea whether religious prejudice is playing any role in the opposition to the temple in McKinney. Often — I think particularly of the Newport Beach California Temple, where I watched the matter pretty closely — it’s there, just concealed. (I note that the construction of a mosque was recently blocked in a Texas community nearby, on the grounds of concerns about “traffic” — an issue that is also cited against Latter-day Saint temples, where it should often scarcely be a factor at all.)

That said, sometimes neighbors have genuine nonreligious concerns, whether well-founded or ill-founded. Should we compromise? And one sometimes has to decide when the fight is worth it and when it’s not. Should we continue to challenge the city council in McKinney? If we do and we win, will it be a pyrrhic victory?

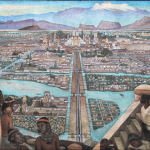

Douglas Stilgoe, who is known to some as “Nemo the Mormon” (although he is in fact no longer a believing member of the Church), flew from his home in England to testify against the proposed temple. Notwithstanding his opposition, Stilgoe made some incontestably true points: It is true, for example, that the validity and value of temple ordinances does not depend upon the size or the splendor of the physical structure in which they’re performed. They could be (and have been) performed on a mountain top under the open sky. They could conceivably be performed in a quonset hut or in a cabin made of adobe bricks. (A friend and I once built such a cabin when we were about twelve or thirteen.) Our temples don’t require steeples or spires to be real temples, as the photographs that I’ve gathered for this blog entry make clear. (See also the designs for the Anchorage Alaska Temple, which is currently being built anew, the Belo Horizonte Brazil Temple, the Singapore Temple, and even the Brasília Brazil Temple.)

Should the Church be obliged, though, to perform temple ordinances in quonset huts or adobe-brick cabins? Obviously not. A sparklingly beautiful temple can, however, be built without a spire. But when is compromise warranted? And when should genuine principles of religious liberty not be compromised?

Is it worth the fight in McKinney? In Wellington, New Zealand? In Heber, Utah? In Cody? Very possibly. If we always compromise, where will it end? If we continually surrender, will we continue to be able to build temples? Will we never again be allowed to include spires?

I believe very strongly in the freedom of religion. And not merely for my own faith. It’s one of the reasons why, many years ago, I came out publicly in favor of the controversial “Ground-Zero Mosque” in New York City.

A friend suggests an interesting possible scenario in McKinney: We sue for the right to build the current design of a temple there. We win. We then voluntarily build a temple with a much smaller spire or even no spire at all. Or, perhaps even better, having once established the principle we then move the temple site to some other place. I would find that quite gratifying, in a way.

Finally, to provide a change of pace, these items have been drawn for your righteous indignation and pleasure from the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™. Read them and weep:

“FamilySearch and NCIP Partner to Preserve Oral Histories of Filipino IPs”

“Un Kilo de Ayuda Will Use Church Donation to Help Nourish 23,000 Children in Mexican States”

[P.S. — I have slightly altered the post above to incorporate my now improved understanding of who “Nemo the Mormon,” Douglas Stilgoe, is. I had not been aware that he is actually a formerly active Latter-day Saint, now turned critic, though I had suspected it. That changes things just a bit.]