One of my nephews — my late brother’s eldest son — has been in town, along with a daughter of his who is participating in a camp at BYU. On Thursday evening, they took us out to dinner at AjiPeru. I enjoyed the lomo saltado and washed it down with glasses of cold chicha morada and maracuya. (I’m not even remotely a “foodie,” but describing meals and menus clearly drives a few of my anonymous online critics mad[der], which is what they seem to live for. So I’m only thinking of them when I post such morsels.)

My nephew holds a doctorate (from a premier graduate program) in engineering, but he’s always had literary inclinations, so he’s now shared with me a manuscript anthology of relatively short meditations — mostly, but not all, of his own composition, in both poetry and prose — on what fatherhood has meant to him and has taught him. I haven’t read the entire manuscript (I only received it on Thursday evening), but there are parts of it that are quite moving and even profound. Not at all the kinds of things that most (I think) would expect when first picking up a book of reflections on being a Dad. He’s now considering possible publication venues, including self-publishing.

He came by our house this morning, and we had a good visit about his manuscript and a host of other things. It’s good to catch up; it’s too easy to let relationships slide through lack of time.

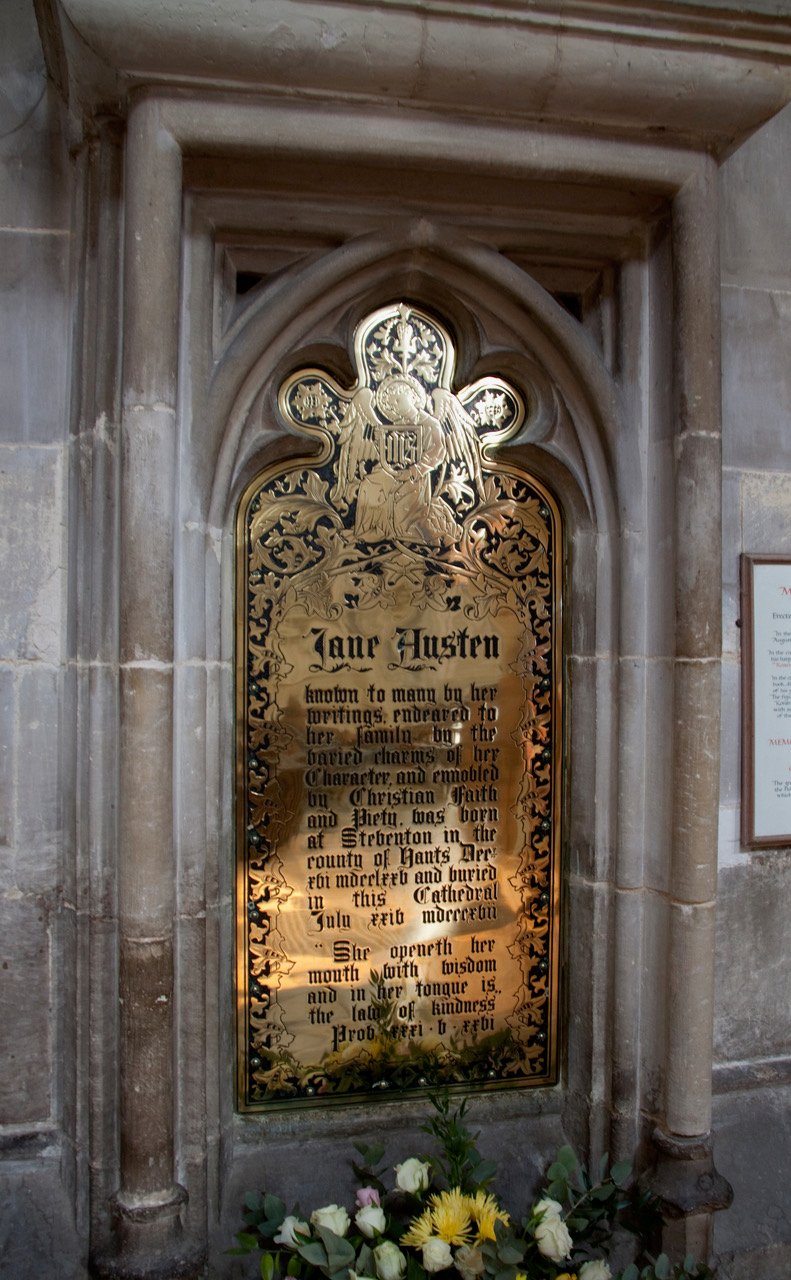

Flipping through the channels late last night, we discovered that the 1995 BBC version of Pride and Prejudice, with Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth, was running on BYUtv. So, being the pre-programmed robots that we are, we instantly sat down and watched the first episode there and then watched two more episodes on my wife’s computer. We would have binge-watched the entire thing yet again — how many times have we watched it and its Keira Knightley alternative? I have literally no idea — but, gradually, as we asymptotically approach mature judgment, we’re coming to recognize our limits. And we knew that our granddaughter would be up early, no matter how late we watched Pride and Prejudice. Partly we were in the mood to revisit Jane Austen’s great story because we had just visited her cottage home in Chawton, Hampshire and done an Austen-themed walking tour in London’s Mayfair district and paid our respects at her tomb in Winchester Cathedral. But we would almost certainly have watched the movie anyway, even if we hadn’t just done yet another Austen pilgrimage. We’re addicts.

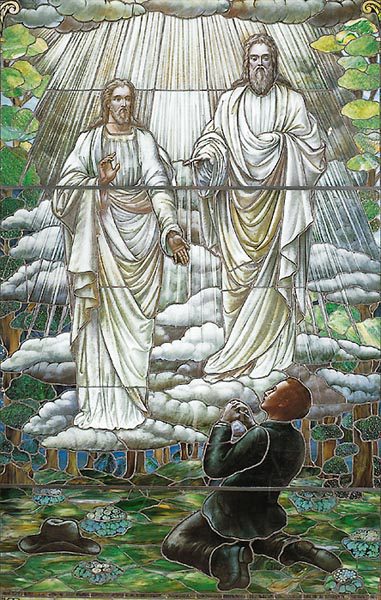

(A stained glass window from roughly 1913)

Wikimedia Commons public domain image

I want to call your attention to a still relatively recent article that I judge to be extremely important: Barry R. Bickmore, “Show Them unto No Man”: Part 1. Esoteric Teachings and the Problem of Early Latter-day Saint Doctrinal History” BYU Studies 62/1 (2023): 29-60. In order to do so, I cite an exceptionally long passage from it, justifying my extended quotation by pointing out that it neatly summarizes the significant argument that Professor Bickmore is pursuing in his essay and that I hope, thereby, to whet your appetite for reading more of what he has to say:

Esotericism is the practice of keeping two sets of doctrines—an “exoteric” set meant to be understood by the general public and an “esoteric” (that is, hidden) set meant to be understood only by believers, or even a privileged subset of believers. What is more, the exoteric teachings may be deliberately crafted to make extrapolation to the esoteric doctrines difficult. For example, it is now widely recognized that esotericism was practiced in early Christianity, and when Jesus’s disciples asked him why he taught in parables, he replied that “it is given unto you to know the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it is not given” (Matt. 13:10–11). Christian writers in the first few centuries after Christ often noted that they were in possession of an esoteric tradition handed down from the Apostles, withheld from unbelievers and rarely written down. Such esoteric teachings clearly existed,5 but although we can find clues about what they involved, their specific content remains largely unknown. Because of this, it is an inescapable fact that historical reconstructions of early Christian doctrinal history must involve a heavy dose of speculation and bias. Regarding the esoteric tradition in early Christianity, Methodist scholar Margaret Barker writes, “It is the unwritten nature of this tradition which proves to be the greatest problem in any investigation which relies entirely on written sources, there being nothing else to use. We can proceed only by reading between the lines and arguing from silence, always a dangerous procedure.”

The bias involved is not limited to the influence of religious, political, or other points of view. In addition, historians approaching the doctrinal history of a religion that incorporates esotericism often exhibit a bias toward downplaying its importance. That is, they make the practical assumption that even if they know they are missing some information about esoteric teachings, that information probably is not critical for drawing correct conclusions about the belief system. For instance, even several decades after the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls showed that Second Temple Judaism was rife with exactly the sort of esotericism practiced in early Christianity, Guy Stroumsa could write that “the existence of esoteric trends in the earliest strata of Christianity . . . [is] still ignored or played down by some scholars.” If its existence is acknowledged, it is too often viewed “almost exclusively within the context of the Hellenistic mystery cults.”

Given that the whole point of esotericism is to withhold from public view the clearest and most advanced expositions of doctrine, downplaying the importance of esoteric teachings seems problematic. But how can we assess the seriousness of the problem, when the issue is one of missing information?

In this essay, I argue that the cost of ignoring esotericism when reconstructing doctrinal history is very steep indeed. To demonstrate this point, I present some examples of early Latter-day Saint doctrinal statements that, upon reflection, appear difficult to interpret correctly without referring to Joseph Smith’s documented practice of esotericism. In these cases, we actually have both the exoteric and esoteric versions of Smith’s early teaching. Among Joseph Smith’s earliest writings are the Book of Mormon and the book of Moses, a pair of documents unquestionably produced by Smith near-contemporaneously and respectively claiming to expound exoteric and esoteric teachings.

I also show that a number of historians have nevertheless proposed pathways of early Latter-day Saint doctrinal change that are demonstrably implausible, precisely because they have misunderstood the exoteric-esoteric relationship between these documents, and because they have too often refused to even consider the possibility that Joseph Smith was working from a sophisticated, and perhaps even successful, plan to restore legitimately primitive aspects of early Christianity. No matter what the source of their bias, it is clear that these historians have made very serious mistakes of interpretation, with the result that they present early Church doctrinal history as much more disjointed than it actually was. (31-33)

I was pleased to see that Professor Bickmore specifically (albeit in passing) addresses some recent attempts to recast the development of Restoration doctrine in what seem to be pretty clearly naturalistic terms, as deriving largely if not entirely from ideas available to Joseph Smith in his mundane intellectual environment rather than from revelation. Such treatments require response.