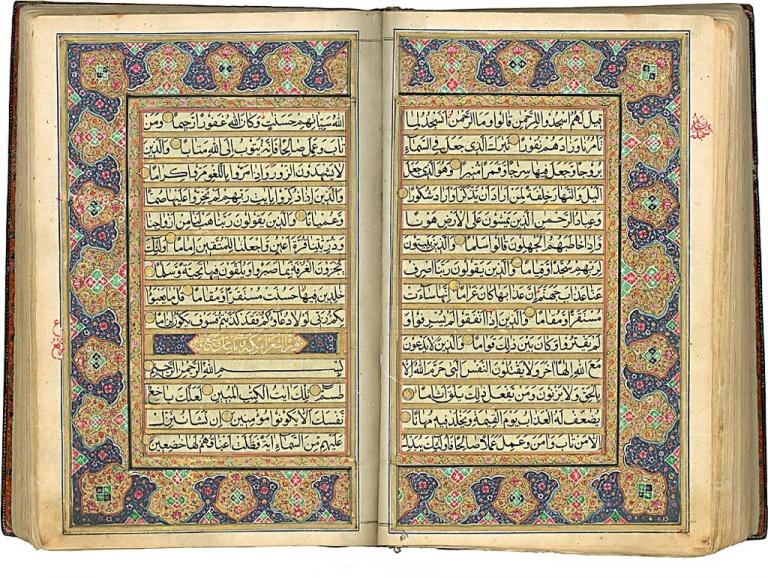

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Continuing — see the first installment here — with some notes that I wrote up, at the request of a committee in Salt Lake City, back in January 2017:

I’ve watched young Turkish boys learning to read the Arabic Qur’an in Arabic script—and seen them pause right in the middle of a word to take a drink or to do something across the room, which seems to me clearly to indicate that they don’t know, or weren’t thinking of, the meaning of what they’re reading.

The Arabic language is extremely rich in rhymes, while English is, relatively speaking, rhyme-poor.

The Arabic Qur’an is written in rhymed prose, usually with entire chapters maintaining the same rhyming sound at the end of each verse. (It lacks meter, though, so it isn’t really poetry.) But attempts to render its rhymes into English result in a monotonous sing-song flavor, which is one reason (though far from the only one) why translations of the Qur’an are thought to lose much of the quality of the original.

Muslim translators believe that they can give their audience a reasonably good idea of the meaning (or meanings) of the Arabic Qur’an, but that their products are, nonetheless, not the Qur’an. They are not the actual words spoken to Muhammad by God.

Translations of the Qur’an sometimes reflect this idea by being titled, for example,

The Meaning of the Glorious Qur’an

The Qur’an Interpreted

The Noble Qur’an: A New Rendering of Its Meaning in English

The Majestic Qur’an: An English Rendition of Its Meanings

or, even,

The Qur’an with an English Paraphrase.

The Magnificent Qur’an: A 21st Century English Translation, published by Ali Salami of the University of Tehran, bills itself as a “conceptual translation.”

***

Some interesting news items related to Islam:

“The Wrong Way for Germany to Debate Islam”

From late last year, but still of interest:

And something of a bit more general scope:

“Antisemitism: How History’s Oldest Hatred Still Holds Sway”