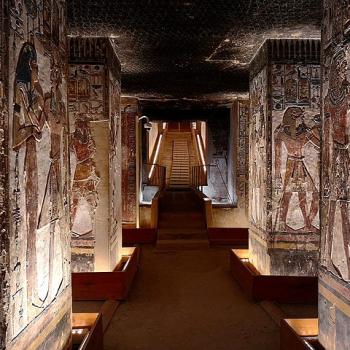

These two statues of Amenhotep IV (Eighteenth Dynasty; ca. 1350 BC), located on the western bank of the Nile, across from Luxor, are all that remains of his massive memorial temple.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

Compare Luke 11:34-36; 12:33-34

1.

The transience of earthly treasures — referring not only to wealth, but to popularity, power, status, beauty, reputation, pleasure, and other such things — is a staple of religious moralizing, and not solely among Christians.

And justly so, because one of the most obvious and undeniable facts of human life is that such things simply don’t last.

Fame, beauty, reputation, power, and popularity typically fade — after death, if not (sometimes quite painfully) long before.

Status doesn’t count for much in the grave.

The famous poem “Ozymandias,” by the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), captures this well:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Moreover, pleasures end. But, very often, they begin to pall and to bore long before they end.

And, of course, great wealth can’t buy us an escape from the grave, and can’t accompany us into the world beyond.

I think, in this context, of an April 1968 General Conference talk given by Elder Spencer W. Kimball:

One day, a friend took me to his ranch. He unlocked the door of a large new automobile, slid under the wheel, and said proudly, “How do you like my new car?” We rode in luxurious comfort into the rural areas to a beautiful new landscaped home, and he said with no little pride, “This is my home.”

He drove to a grassy knoll. The sun was retiring behind the distant hills. He surveyed his vast domain. Pointing to the north, he asked, “Do you see that clump of trees yonder?” I could plainly discern them in the fading day.

He pointed to the east. “Do you, see the lake shimmering in the sunset?” It too was visible.

“Now, the bluff that’s on the south.” We turned about to scan the distance. He identified barns, silos, the ranch house to the west. With a wide sweeping gesture, he boasted, “From the clump of trees, to the lake, to the bluff, and to the ranch buildings and all between—all this is mine. And the dark specks in the, meadow—those cattle also are mine.” . . .

That was long years ago. I saw him lying in his death among luxurious furnishings in a palatial home. His had been a vast estate. And I folded his arms upon his breast, and drew down the little curtains over his eyes. I spoke at his funeral, and I followed the cortege from the good piece of earth he had claimed to his grave, a tiny, oblong area the length of a tall man, the width of a heavy one.

Yesterday I saw that same estate, yellow in grain, green in lucerne, white in cotton, seemingly unmindful of him who had claimed it. Oh, puny man, see the busy ant moving the sands of the sea.

Moreover, wealth cannot ultimately satisfy. It’s not bad, in itself, but it lacks the power to cure most ills, or to still our psychological and spiritual hungers.

Edwin Arlington Robinson’s 1897 poem “Richard Cory” is a memorable statement of this theme:

(If you’d like, listen to Simon and Garfunkel’s musical recasting of Robinson’s theme in their own “Richard Cory.” It’s less than three minutes long: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dwqwAy85CgY.)

2.

“The eye is the lamp of the body. So, if your eye is sound, your whole body will be full of light; but if your eye is not sound, your whole body will be full of darkness. If then the light in you is darkness, how great is the darkness!”

Perhaps this reflects some ancient theory of vision and physiology. Surely it’s meant to be taken metaphorically.

But what a powerful metaphor!

I think of the cynics with whom I come in too-frequent contact. How great is the darkness! Some people seem to see everything darkly. All is, to them, sordid, self-interested, pointless, a snare and a delusion, an occasion for sneers.

I pray that I never come to that point. I pray that they escape from it.