This Greek Orthodox monastery stands beside the ruins of ancient Capernaum, where the exchange recounted in John 6 occurred.

Some critics that I’ve come across seem to imagine that, if the Church were really true, people would be lined up to enter the font, nobody would ever fall away, and all customers would be completely satisfied and unfailingly enthusiastically willing to pay the price. Everything that the Church taught would be pleasing to everybody, and instantly accepted without reservation.

The fact that the situation isn’t so, they believe (or pretend to believe) demonstrates that the claims of the Restoration are false.

This passage suggests the vacuity of that notion. At least, it should to a believing Christian.

Compare Matthew 18:18; John 6:66; 20:22-23

Compare Matthew 18:18; John 6:66; 20:22-23

I.

The passages of the synoptic gospels listed above are absolutely crucial to the claims of the papacy and the Roman Catholic Church. Right around the base of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, in enormous letters — see the photograph above — Jerome’s Latin Vulgate translation of the words of Jesus to Peter declares the authority of Peter and his papal successors: Tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam. “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock [hanc petram] I will build my church.” Everywhere in that massive basilica, the symbols of the popes prominently feature the crossed keys of Peter, and painting after painting of Peter, there and elsewhere, identifies him by placing large keys in his hands.

But the passage is crucial to the claims of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well. And, on this point, those are clearly rival claims. (See pages 105-107 of an article that I published in Interpreter back in 2015 for a comment on precisely this topic.)

Allow me to provide some notes toward a Latter-day Saint reading of this portion of Matthew 16:

a.

As is very often the case in the New Testament, the term heaven in the phrase my Father who is in heaven (Mt 16:17) actually reflects an underlying Greek plural, heavens: ὁ πατήρ μου ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς. This goes back, literally, to the biblical beginning: The King James Version’s In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth could more precisely be rendered as In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth [בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ]. Although English translations usually obscure this, the biblical text almost always (or virtually always) refers to multiple heavens.

b.

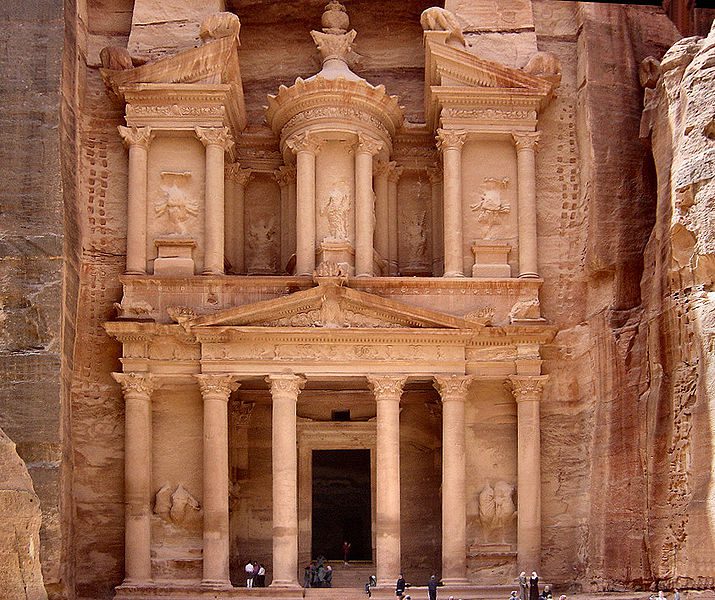

There’s a crucial difference, in Greek, between the masculine petros (which is given to Cephas as a name) and the feminine petra. Petros refers to a stone, a smallish one of the kind that you might skip across a pond. Petra refers to a massive rock, like that at Gibraltar. Or like that at . . . well, Petra (see the photo above), the ancient city in Jordan that was carved right into the red sandstone cliffs of Edom.

“You are Peter [petros],” says Christ to his chief apostle, “and I will build my church upon this rock [petra]”: σὺ εἶ Πέτρος, καὶ ἐπὶ ταύτῃ τῇ πέτρᾳ οἰκοδομήσω μου τὴν ἐκκλησίαν.

There’s clearly a play on words going on here, but it contrasts the smallness (and instability? compare Mt 16:21-23, just a few verses later in the same chapter) of Peter as an individual with the solidity of the firm foundation upon which the Savior intends to build his church. I think it no coincidence that Jesus made this statement at Caesarea Philippi (see the photo above), which sits at the base of a substantial rock cliff where the headwaters of the Jordan River gush from the base of Mount Hermon. It’s a powerful visual aid.

c.

But it’s more than that.

Mount Hermon and the specific area of Caesarea Philippi (known today as Banias) were held sacred by many different faiths. In the photo above, you can see a cave that was once holy to the Greek god Pan — which is the source of the name Banias (because Arabic lacks a letter p). Out of the photo to the upper left is a Druze shrine. (The Druze are an esoteric offshoot of Islam. Many of them live in the Golan Heights, adjacent to Banias.)

Water coming out of the base of a mountain was seen as miraculous; caves were regarded as passageways to the underworld, to the realm of the dead.

Mount Hermon has been suggested by some as the site of the Transfiguration of Jesus, which, for Latter-day Saints, would imply temple connections (because many Latter-day Saints believe that priesthood keys were bequeathed to Peter, James, and John there). So it’s appropriately temple-like to have the waters of life issuing forth from the base of a temple-mountain. (Think where temple baptistries are located, within “the mountain of the Lord’s house.”)

In light of the foregoing, Mt 16:18-19 takes on a particular significance for Latter-day Saints:

Jesus says that he’s going to give to Peter “the keys of the kingdom of the heavens” (heavens, again, in the plural: τὰς κλεῖδας τῆς βασιλείας τῶν οὐρανῶν), the power to bind and loose in “in the heavens.” And, says the King James Translation, “the gates of Hell” won’t prevail against the Church. But KJV’s the gates of Hell misrepresents the Greek πύλαι ᾅδου, which really reads “the gates of Hades.”

“Hell” is a place of evil, so, with that in mind, many people have misread this promise as a pledge that the power of evil would never overcome the Christian church, and, specifically, as a refutation of the Latter-day Saint teaching of a universal apostasy of the ancient church.

Hades, however, is simply the place to which all the dead go, both good and bad. As such, it has no particular connotation of wickedness. It’s just a reference to the realm of the dead, to the spirit world (Hebrew she’ol), or to Death itself.

Thus, Peter is going to be given keys that will permit his authority to extend beyond the gates of death. Sealing power, in other words.

A significant text about temples and the power of their ordinances to pass the portals of the grave.

II.

I’ve always found Peter’s response to Jesus’ question (at John 6:67-68) quite moving:

“Jesus said to the twelve, ‘Do you also wish to go away?’ Simon Peter answered him, ‘Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.”

This is the way I’ve felt, when aggressive anti-Mormons have summoned me to reject my own faith and accept theirs. With all respect, I can’t help but think of the words of the sixteenth century Hindu princess and mystic poet Mirabai:

“I have felt the swaying of the elephant’s shoulders; and now you want me to climb on a jackass? Try to be serious.”