Wikimedia Commons public domain image

I grew up not far from the San Gabriel Mission — more properly, the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. I saw it nearly every day of my life for my first seventeen years; it was essentially across the street from my high school. And I’ve visited most if not all of the other Spanish missions in California. That’s part of the reason behind my writing this article for the Provo Daily Herald back in 2001:

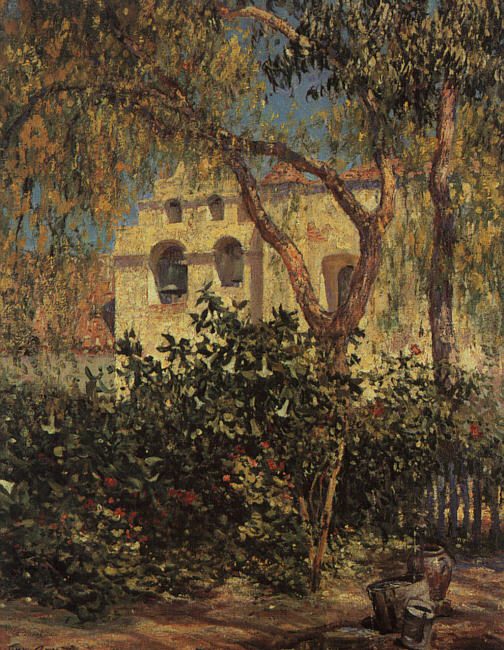

The oldest historic buildings along the Pacific shore of the United States are the twenty-one (mostly eighteenth century) California missions. Established as remote colonial outposts of a Spanish empire in the twilight of its glory, they are young by Middle Eastern or even European standards. By American standards, though, they are venerable.

When, after expelling the Muslims, Spain emerged unified under Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, its warrior aristocrats, in whom the spirit of the Crusades still lingered, sought new lands for conversion and wealth. Eventually, they claimed all of Mexico and Central America, the Caribbean, half of South America, and much of the present-day United States.

But California’s colonization came relatively late, nearly two centuries after San Diego and Monterrey had been mapped. And, even then, the Spanish viceroy was moved to action only when the Russians showed interest in the region. The assignment to take Christianity to California fell, in 1769, to a Franciscan priest named Junipero Serra.

He succeeded brilliantly. By his death in 1784, he had established nine missions. The first two anchored the port settlements of San Diego and Monterrey; the other seven were designed to link them. With the addition of twelve further missions by Father Serra’s successors, each settlement lay a stiff day’s march from its nearest neighbor. The first missions were built near the coast, so that they could be supplied by sea. As the Spanish felt more secure, they began to establish missions further inland. A separate string of them was planned for the Central Valley, but the mission system collapsed before they could be built.

While the Catholic padres indisputably intended to spread Christian doctrine and save souls, the Spanish government, which supported them, had political ends in mind. Spain realized that the vast and distant territory of California would be very difficult to settle and control. Approximately 100,000 native Americans lived there at the time. But Spain found a way of extending its empire that required few men and little money. One or two priests, protected by a few soldiers and given an initial load of supplies, could set up a mission that would soon become self-supporting.

As they appear now, the missions are usually little more than a chapel and some surrounding buildings. In their heyday, though, they were hives of economic activity. A typical mission supported a weavery, a pottery, a winery, a blacksmith’s shop, and a tannery, along with its church and agricultural plantation. Indian villages soon clustered around each mission settlement, first attracted by bright beads, clothing, and food, but rapidly assimilated into the mission economy. The padres’ plan—and, happily, the government’s plan as well—was not only to Christianize the natives, but to teach them basic manual skills along with reading and writing. They hoped they would then become genuinely Spanish in both culture and political loyalty. The Franciscan fathers held the properties in trust, and intended, when their Indian charges were ready, to turn everything over to them and move on.

The political success of the mission system is shown in the fact that a mere 300 soldiers, dispersed along a line more than 650 miles long, were able to control virtually all of modern California. Its religious success appears in the fact that, at the end, when the Mexican government ordered the “secularization” of the missions in 1833, 60 padres ministered to the spiritual needs of roughly 31,000 Christianized natives.

But it was the very economic success of the missions that led to the end first of Spanish and then of Mexican control. The missions’ ability to sustain themselves soon gave rise to thoughts of political independence. And the wealth of California quickly drew the attention of others—most notably that of the vigorous new English-speaking nation to the east.

The Spaniards first came to California seeking gold, but never found it. Ironically, Mexico lost control of the area to the United States just two years before the California Gold Rush, which began only ninety miles from Sonoma where the last mission had been founded. Two years and a few miles prevented California from becoming a rich Mexican province, or perhaps even an independent and wealthy Spanish-speaking nation of its own.

Posted from Tempe, Arizona