***

First, though, don’t miss this newly published item on the website of the Interpreter Foundation:

***

This portion of today’s post is continued from “Addendum 5: Founding the Middle Eastern Texts Initiative at BYU (Part 1)”:

PROFESSOR DR MORITZ-MARIA VON IGELFELD often reflected on how fortunate he was to be exactly who he was, and nobody else. When one paused to think of who one might have been had the accident of birth not happened precisely as it did, then, well, one could be quite frankly appalled. . . .

Of the three professors, von Igelfeld was undoubtedly the most distinguished. He was the author of a seminal work on Romance philology, Portuguese Irregular Verbs, a work of such majesty that it dwarfed all other books in the field. It was a lengthy book of almost twelve hundred pages, and was the result of years of research into the etymology and vagaries of Portuguese verbs. It had been well received — not that there had ever been the slightest doubt about that — and indeed one reviewer had simply written, ‘There is nothing more to be said on this subject. Nothing.’ Von Igelfeld had taken this compliment in the spirit in which it had been intended, but there was in his view a great deal more to be said, largely by way of exposition of some of the more obscure or controversial points touched upon in the book, and for many years he continued to say it. This was mostly done at conferences, where von Igelfeld’s papers on Portuguese irregular verbs were often the highlight of proceedings. (Alexander McCall Smith)

So, as I say, Elder Alexander B. Morrison of the Seventy took the idea of a dual-language translation series of classical Arabic texts back with him to Church headquarters, and, as a result of his report, I received an unfunded mandate from Salt Lake City to launch the project. Whether the initial mandate came from the BYU Board of Trustees or from the First Presidency or from the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve or from some other combination of Church leaders I never knew. I never asked. I just never thought to do so. What it meant, though, of course, was that I was to launch the effort but also that, in order to do so, I first had to raise the money to make it possible.

This was no easy thing. I’ve never liked asking people for their money, and fundraising takes real effort. Every once in a while, somebody simply steps forward — sometimes almost (or even entirely) without waiting an invitation — but that’s not usually the case. And only a small proportion of those who are asked to give will actually do so.

Fortunately, the Brethren suggested a name — that of the late Utah multibillionaire James L. Sorenson (1921-2008) — telling me to ask him to support the undertaking. And the BYU Development Office allowed me to call upon one of their donor liasons for help. Eventually, too, the provost of BYU, Bruce Hafen — later, Elder Bruce C. Hafen of the First Quorum of the Seventy and, thereafter, President Bruce C. Hafen of the St. George Utah Temple — stepped in, as well. Unfortunately, Brother Sorenson wasn’t initially disposed to give. As I came to know him (and to personally like him) through repeated visits, he made it pretty clear that he was pestered a great deal by people who wanted his money for this purpose or that purpose and that he regarded most such requests as frivolous. He himself lived a relatively simple life, driving a Ford Bronco (if I recall correctly) and occupying a simple and unglamorous office in a not very picturesque industrial area in the southern part of Salt Lake City. He felt, and I had to agree with him, that his fortune did much more good for people when it was invested, as much of it actually was, in the development of medical technology and in genetic research than it would do if it were handed over to Dr. Dryasdust for his work on the use of the Greek particle te in the fragments of Euphorion, Philicus, and Posidippus or to Herr Professor Doktor Totundtrocken to support further research into the social psychology of Japanese fire belly newts.

With the passage of time, though, to make a long story short, Brother Sorenson did eventually make a donation that enabled me to announce the launch of the Islamic Translation Series at an evening event at the Middle East Institute at Columbia University in New York City. (Thereby hang several interesting and often amusing tales that I will not share here — including a private lunch in which a third of the Quorum of the Twelve effectively pitched in on my behalf as fundraising assistants, to no avail, and during whicn President Howard W. Hunter said something that still makes me laugh even today — but that I have sometimes recounted orally in small groups and that I will probably, someday, write up and deposit among my papers in BYU Special Collections. Maybe I’ll tell the President Hunter story before then, though. It won’t embarrass anybody who is still alive.) Soon thereafter, I found that I had unexpectedly become something of a minor folk hero with the BYU Development Office. It turned out that they had been trying to secure donations from Brother Sorenson to BYU for many years, but without success. Had I been aware of that long record of failure, I might never have made the attempt. But, as the saying goes, fools rush in where angels fear to tread.

I recall one aspect of the event at Columbia that made a particular impression on me. My announcement was brief, and there were plenty of other things and people on the program. When the formal affair was over, though, one particular man rushed up to shake my hand and to ask me a question. It was the ambassador to the United Nations from the Islamic Republic of Iran. He pumped my hand excitedly, and asked me “Why are the Mormons doing this?” I was a bit surprised. I had said absolutely nothing about the Mormons or the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Obviously, though, he knew something about Brigham Young University and about who sponsored it. I can’t really recall how I answered his question. But I would be asked that question many more times, and I gradually came up with a pretty standard answer. I’ll share it here at some future point. I think that the first time that I came up with it was during a brief telephone interview with Gustav Niebuhr, then a religion writer for the New York Times who is also, among other things, a grandson of H. Richard Niebuhr and a great nephew of Reinhold Niebuhr, two of America’s most distinguished Protestant theologians. (See “Religion Journal; A Professor in Nanjing Takes Up Jewish Studies.”) Unfortunately, he didn’t use it. As he explained to me, he had only a very little space left to him in an article that he had already basically written, but he had only just heard that Brigham Young University was doing an Islamic Translation Series, and he was totally intrigued.

Right now, however, I want to get in another word about funding for the translation project: Eventually, I received some additional budgetary help, and in an interesting way. I was walking one day through what was then known as the BYU Bookstore. (Today, it’s just the “BYU Store.” But the sad demise of bookstores is too melancholy a tale for me to want to tackle it just now. Not from here in Hawaii, with a breeze blowing through the palm trees and the sound of the surf pounding gently away in the distance.) Anyway, across the store, I saw that Elder Neal A. Maxwell of the Quorum of the Twelve was standing all alone, browsing in a book. Actually, it’s something of a distortion to say that he was all alone. There was, truth be told, virtually a perfect circle of BYU students standing around him, pretending themselves to be browsing among the bookshelves. Elder Maxwell was the center of the circle, of course, and its radius was roughly twenty or thirty feet.

By this time, I had already had some very limited contact with Elder Maxwell, but I determined immediately that I would not bother him, that I would allow him to continue to leaf through his book undisturbed.

I had begun to walk past him at a distance of approximately fifteen or twenty feet when he looked up and called out “Dan!” So I walked over to him. He explained that he had been on campus for meetings with the University president and other officers and that, as he put it, his wife Colleen had given him permission to look at some books in the BYU Bookstore while he was down from Church headquarters. He asked me how the translation project was coming, and I responded that I was still in fundraising mode. “Oh,” he said, “you shouldn’t have to spend your time begging for money.” Elder Maxwell had served from 1970 until 1976 as the Commissioner of Church Education (after a career mostly spent at the University of Utah, where he had eventually become the University’s executive vice president); Henry B. Eyring was the Commissioner at the time of this conversation. The Commissioner of Church Education , Elder Maxwell told me, had a little “slush fund” of discretionary money to spend on special projects — slush fund was exactly the phrase that he used, with a twinkle in his eye — and so, he said, “I’ll talk to Hal a little bit; he can help you out.” And, indeed, the Church did help. The financial needs of the translation project weren’t particularly enormous and, between Jim Sorenson and the Commissioner’s office, we were off to a reasonably good start.

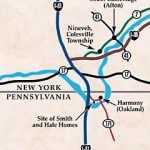

I wasn’t sure, though, how I was going to proceed. But then, shortly after that event at Columbia University, I was back in upstate New York to participate in a conference on ancient Greek and medieval Islamic philosophy at the State University of New York at Binghamton (or, as it tends to be called these days, at Binghamton University). Sitting in on one session, I heard the host of the conference, Professor Parviz Morewedge (pronounced either as the English more-wedge or as the more authentically Arabo-Persian mur-ah-wij; he himself doesn’t seem to care much, one way or the other), close a presentation by describing his dream of a bilingual translation series devoted to the great works of the Islamicate philosophical and scientific tradition. I made a beeline for him and introduced myself.

He became my very vivid and colorful friend and my indispensable associate in the work of launching the Islamic Translation Series. He knows everybody, and he has a positive genius for getting them to want to do things that they would never otherwise have done. Once again, I could tell you stories. Oh, yes indeed. Lots of them. Including some very funny ones. But I won’t. Not right now, anyway.

To be continued.

Posted from Ka’anapali, Maui, Hawai’i