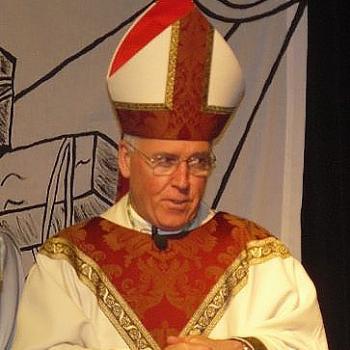

The man who was the most visible spiritual leader to New York’s Roman Catholics on September 11, 2001 is sharing his memories of that day with the AP:

Cardinal Edward Egan was eating breakfast when then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani called to say there was a tragedy and the churchman was needed. A police car would soon be outside the chancery to take the leader of New York’s Roman Catholics downtown.

Egan didn’t know exactly what had happened in lower Manhattan that morning as he and his priest-secretary hurtled through the city. He couldn’t decipher the crackle of the police radio and didn’t have access to news. Giuliani first said he was sending Egan to provide support at a makeshift morgue on the city piers, then redirected the cardinal to St. Vincent’s Hospital, so he could tend the injured.

Within 90 minutes, Egan would be standing in the doorway of St. Vincent’s looking south to Wall Street as the World Trade Center crumbled. He would spend the next several days anointing the dead, distributing rosaries to workers as they searched, mostly in vain, for survivors, and presiding over funerals, sometimes three a day.

“For about five or six years, monsignor and I wouldn’t talk to anybody about it,” said Egan, referring to his priest-secretary, Monsignor Gregory Mustaciuolo, who was with him in the days following the attacks. “It was too much of a horror.”

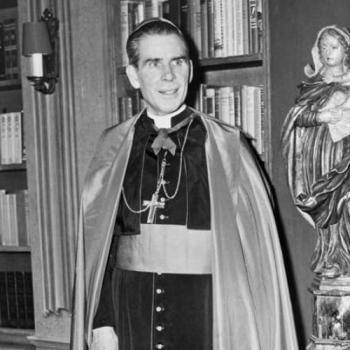

Egan had been appointed New York archbishop the year before 9/11. He succeeded the late Cardinal John O’Connor, a stand-out personality even in a city full of them, who became the most forceful Catholic voice in the national debates of his era.

Egan had worked as an auxiliary bishop under O’Connor, then as bishop in nearby Bridgeport, Conn. But his tenure as archbishop would be decidedly different. An often stern, 6-foot-4 Latin scholar who was fluent in several languages, he had to focus on internal church issues, taking on the unpopular task of fixing the financial problems his beloved predecessor left behind.

Still, the cardinal cared deeply about the civic and ceremonial duties that came with the job, the highest-profile religious position in the city.

Decades earlier, while serving under Chicago Cardinal John Cody, he recalled a moment during the 1968 riots there when he rode in a car with Cody and Mayor Richard J. Daley through the city’s West Side as it burned. Daley and Cody were crying.

“I saw it (9/11), and thought, ‘This has now happened to me,'” Egan said. .

When the cardinal arrived that morning at St. Vincent’s, he donned hospital scrubs, then along with the nuns, he waited.

He noticed that an intern nearby was trembling and asked what was wrong. The physician said his father worked on the 102nd floor of the north tower, so the cardinal suggested the two go into a side room and talk. The young man declined. “He said, ‘I am a doctor. The injured are coming. This is my place,'” Egan recalled. A couple of months later, Egan would recount this story to Pope John Paul II, who would send a check to the young physician to help cover his medical school costs.

The cardinal next remembers giant dust clouds appearing. People were running by, screaming, trying to stay ahead of the debris. At first, no one in St. Vincent’s knew the source of the mess. The police commander who was with Egan handed him a gas mask.

“I wore that gas mask for days,” Egan said. “When I would get home at night, I would have the rubber marks stuck on me. And I know that in some of the pictures of me in the cathedral, I had those marks.”